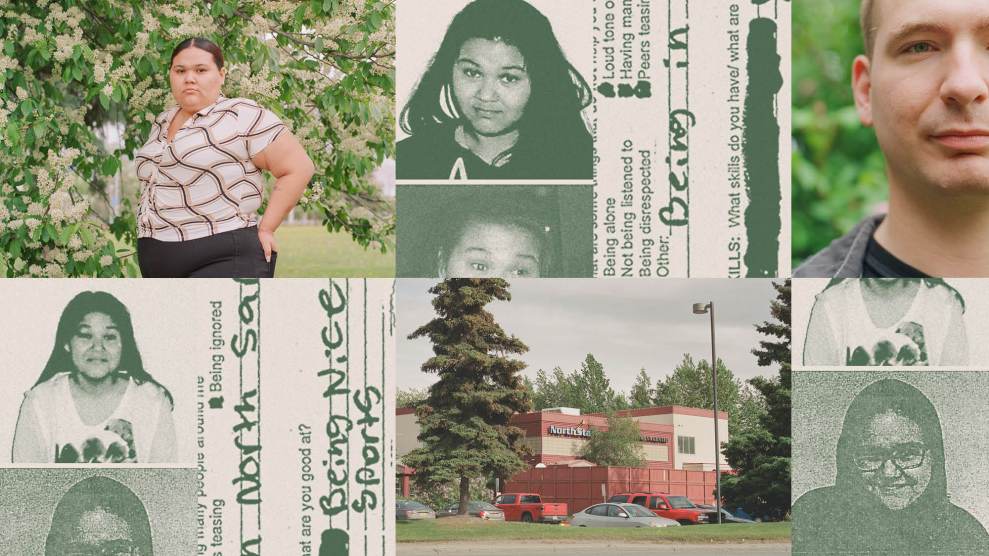

Mother Jones illustration; Ash Adams

Universal Health Services, the country’s largest psychiatric hospital chain, claims on its website to provide compassionate care with a “relentless focus on quality” to thousands of patients each year. And it does well by investors, too: The publicly traded, Fortune 500 company brought in $13.4 billion last year.

But a yearlong Mother Jones investigation tells a different story, shedding light on a large, profitable, and often-overlooked patient base: foster kids.

Thousands of foster kids have been admitted in recent years to UHS’s psychiatric facilities, where they typically stay for weeks or months, sometimes leaving far worse off than when they arrived. Some of their claims echo allegations that have come up in damning government and media investigations about UHS for years: that the facilities improperly use physical force and chemical restraints, fail to provide adequate treatment and staffing, admit patients who don’t need to be there to begin with, and bill insurance for unnecessary services over excessive lengths of time. (In a statement, UHS denied these allegations, pointing to its positive clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction scores.)

To UHS and its competitors, foster kids are “a gold mine,” says Ron Davidson, a psychologist who spent two decades investigating psychiatric facilities.

Foster children make for profitable patients for the same reasons they’re so vulnerable: There’s rarely an adult on the outside scrambling to get them out, and often, they don’t have anywhere else to go. Plus, Medicaid typically foots the bill. Over time, a symbiotic relationship has developed between overburdened child welfare agencies, which have more foster kids than foster homes, and large, for-profit companies like UHS, which have beds to fill. “The sales pitch—‘We can offer solutions to your overwhelming caseloads of high-needs children’—appeared irresistible to frantic agencies in need of more beds,” Davidson says.

Our investigation tells the story of Katrina Edwards, a former foster child in Alaska who spent more than three years during her adolescence at facilities owned by UHS, including 891 nights at North Star Behavioral Health in Anchorage. Medical and court records show that she was repeatedly physically restrained, forcibly injected with a sedative, held in seclusion, and put on potent psychiatric medications. At times, she stayed at North Star for months after she was ready for discharge, simply because there was no foster home available for her. “They got a lot of money from me,” Edwards says. She’s right: Alaska’s Medicaid program paid more than half a million dollars for Edwards’ care at UHS facilities.

Our reporting found that Edwards’ story is one of many examples of foster kids spending long stretches locked in scandal-plagued UHS facilities. The investigation is based on records requests to each state, interviews with more than 50 people, and thousands of pages of medical and court records. Here are some key takeaways:

Foster kids are revenue generators.

The sheer scale of UHS’s operation is difficult to fathom: Foster children from 38 states were admitted to UHS’s psychiatric facilities more than 36,000 times between 2017 and 2022. Over the same period, 31 states spent more than $600 million on the treatment of foster children at the company’s facilities.

Alaska, Edwards’ home state, exemplifies the company’s dominance: Two-thirds of the foster kids sent to psychiatric facilities go to places owned by the company. These placements disproportionately affect Black and Indigenous kids, who are more likely to enter the foster system and more likely to be sent to residential treatment facilities.

States turned a blind eye to problematic facilities.

Child welfare agencies routinely send foster kids to UHS treatment centers with alarming track records.

“It is a huge, huge market, dollarwise," Davidson says. "And the thing that irritates advocates and people like me is that so much of this marketplace is either unnecessary or patients could far more easily be treated at far lower cost in outpatient care.”

Over the past six years, foster kids from more than a dozen states were sent to Utah's Provo Canyon, perhaps the most infamous UHS facility. Celebrity heiress Paris Hilton experienced physical and sexual abuse at the facility as a teenager, before it was under UHS ownership, and has taken aim at the facility in her work advocating against the so-called "troubled teen industry." Under UHS ownership, damning allegations about the use of physical restraints and sedative injections at the facility have continued. Hilton told me over email, “Provo hasn’t changed and never will.”

UHS noted that, in the event of allegations of mistreatment, facilities investigate and take remedial actions. The company also said it complies with regulations related to “restrictive practices.”

Foster kids were warehoused at UHS facilities.

In some cases, employees of child welfare agencies have admitted that children in state custody are being unnecessarily institutionalized. Take the case of Nathon Pressley, who was sent to North Star again and again as a foster child, starting when he was just 5 years old. As an adult, he sued Alaska’s Office of Children's Services for negligence. In a 2018 deposition, then–OCS director Christy Lawton admitted that foster children stay at North Star—even after Medicaid stops paying—when the agency can’t find a placement for them. In a deposition the following year, the agency’s expert witness, Lindsay Bothe, acknowledged that Pressley “did have some longer stays while they were looking for a placement for him to discharge to.” Pressley’s lawyer, Jim Davis, then pressed Bothe:

Davis: Nathon didn’t really belong at North Star anymore because he didn’t meet that level of care, and he was already stabilized, at least as far as North Star goes, but there wasn’t anyplace else with the right level of care to put him?

Bothe: Correct.

Davis: So he just stayed locked up in a psychiatric facility?

Bothe: Yes.

Davis: For months.

Bothe: Yes.

Data suggests that Pressley's situation isn't an isolated case. Over a three-year period, OCS paid North Star more than $1 million for the care of foster children whose stays weren’t covered by Medicaid.

In a statement, OCS said that it strives to find appropriate placements for foster kids with behavioral health needs, but some children do experience delays as they wait for a lower level of care.

There are damaging—and long-lasting—consequences.

As our investigation notes:

For some foster children, the results have been devastating. As Edwards endured her stay at North Star, a 12-year-old West Virginia foster child was placed at UHS’s Cedar Grove Residential Treatment Center, a program in Tennessee for sexually abusive and reactive boys, even though he wasn’t a sex offender. He begged his caseworker to let him leave but was held at the facility for 18 months, according to a subsequent lawsuit against the state’s CPS agency. In 2018, Oregon CPS sent a 14-year-old girl to Provo Canyon School, where she experienced 42 instances of peer assault, seclusion, or restraint—including being forcibly injected with the antipsychotic Haldol 17 times—over the course of three months, according to records obtained by state officials. The same year, Virginia’s CPS agency sent 17-year-old Raven Nichole Keffer to UHS’s Newport News Behavioral Health Center, where she collapsed after days of complaining of feeling sick. According to a lawsuit, a 15-year-old patient was the first to call 911; Keffer died of an allegedly preventable adrenal insufficiency. In 2021, Alabama CPS placed a 10-year-old at UHS’s Alabama Clinical Schools, where he was repeatedly assaulted by staffers over six months, resulting in a broken collarbone and black eye, in addition to being bitten by scorpions in his bed “many times,” according to a recent lawsuit. When he reported the injuries, staffers allegedly threatened to kill him.

In its statement, UHS noted it couldn’t comment on ongoing investigations, pending lawsuits, or specific patients, though it did say the incident at Newport News “was the only death of a patient while in the care of the facility.” The statement added, “Our facilities are highly regarded, trusted providers of behavioral health services in the communities we serve.”

The finger-pointing continues.

Experts like Davidson say there are two groups to blame for the unnecessary institutionalization of foster kids: the companies operating problematic psychiatric facilities, and the child welfare agencies who send foster kids to those facilities. In court, the two groups have blamed each other. When Pressley sued OCS, the child welfare agency subsequently sued North Star. Both ultimately settled with Pressley last year for an undisclosed sum.

Katrina Edwards sued, too; she's alleging battery and false imprisonment in an ongoing lawsuit against North Star and UHS. But in her case, the blame-shifting has reversed course: North Star turned around and sued OCS. (The defendants in Edwards’ case have denied the allegations.) Neither organization, it seems, is prepared to take full responsibility for the children in their care.