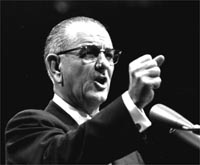

Photo: Associated Press/Wide World Photos

This is a jaded time in American politics. White House handlers carefully choose crowds, backdrops, and camera angles, and it feels as though every large-scale political event has been scripted down to the clothes the crowd is wearing. So it’s hard to avoid getting a little wistful reading accounts of Lyndon Johnson’s arrival in Detroit four decades ago, on May 22, 1964. He was barely into his presidency, and on his way to Ann Arbor to give a speech laying out his vision of a “Great Society,” the initiative that, along with the Vietnam War, has come to define his place in our history.

When LBJ landed at Metropolitan Airport and got off Air Force One — the same airplane on which he’d taken the oath of office six months to the day earlier — there were 30,000 people waiting for him: families that had taken their kids out of school; the entire eighth grade class of St. Alfred parochial school in the Detroit suburb of Taylor; union locals, Democratic Party clubs, curious Detroiters. So many people wanted to see Johnson, in fact, that an hour before he arrived traffic was backed up for two miles leading to the airport. Clearly this was a citizenry that felt a part of public life.

It was an election year, so Johnson acknowledged the crowd’s enthusiasm by joking, “My first thought is to sing an old song, ‘Will You Love Me in November as You Do in May?'” Still, it was not a partisan moment. Johnson invited Democrats and Republicans alike to join him on the tarmac before he got in a helicopter and flew to Ann Arbor, where he addressed a crowd of 90,000 at the University of Michigan stadium.

It was an extraordinary speech in an extraordinary year, really the passage from one era to the next. If you consider what was on the charts at the time — Louis Armstrong’s version of Hello Dolly; the Beatles’ I Want to Hold Your Hand; Roy Orbison’s Pretty Woman — it all seems pretty upbeat and innocent. But by the time Johnson went to Michigan, a set of lasting fault lines were becoming visible in the American polity. Rachel Carson had published Silent Spring in 1962; a year before that, Jane Jacobs had published ‘The Death and Life of Great American Cities,’ her attack on urban renewal and the ignorant despoliation of city centers. Johnson arrived in Detroit at the beginning of Freedom Summer, when thousands of civil rights activists, white and black, descended on the South to register black voters. Three months after his Ann Arbor speech, Congress passed the Tonkin Gulf resolution. Much of what we’ve come to identify with the 1960s and beyond was in evidence, but the U.S. was still living in the comforting glow of postwar confidence and Kennedy-era optimism.

Johnson saw the danger signs and the possibilities alike. The question, for him, was how to attend to the former and build on the latter. What kind of society, he wanted to ask, can we craft? And that is what he went to Michigan to talk about.

Reading the speech today, it’s impossible to not be impressed by how prescient Johnson was. He touched on our “hunger for community” long before it became the subject of learned head-shaking and alarmed conferences. Nobody had even heard the word “sprawl” as we mean it today, let alone made a big deal about a loosening commitment to neighborhood and the loss of green space, but Johnson brought it up — though he called it “expansion” — and worried about how it was breeding “loneliness and boredom and indifference.” He talked about bringing an end to poverty and racial injustice, to the decay of inner cities, to the disappearance of open land and the loss of historic places. He worried about air and water pollution, and fretted about the quality of education. “In many places,” he said, “classrooms are overcrowded and curricula are outdated. Most of our qualified teachers are underpaid, and many of our paid teachers are unqualified. … Poverty must not be a bar to learning, and learning must offer an escape from poverty.” This was, let me remind you, 40 years ago.

In recent decades, derision has been heaped on the programs Johnson created to address his concerns, sometimes justifiably. Yet the national accomplishments that flowed in the wake of this speech — the civil rights and voting rights acts, Medicare and Medicaid, education funding, the endowments for the arts and humanities, the expansion of parks, the protection of clean rivers and wilderness — remind us that Johnson changed the political, social and actual landscape for good. We’re still living in the world he created.

Maybe it’s because he was president at a time when “public-spiritedness” meant more than just the vocal expression of private religious faith, but Johnson clearly knew that he could appeal to his country’s better nature — that when he suggested using government to make this a more beautiful and appealing nation and help those stranded by a changing economy, Americans would respond. “Will you join in the battle to give every citizen an escape from the crushing weight of poverty?” he asked that enormous crowd, and they cheered. “Will you join in the battle … to prove that our material progress is only the foundation on which we will build a richer life of mind and spirit? There are those timid souls who say this battle cannot be won; that we are condemned to a soulless wealth. I do not agree.” Once again, we Americans are struggling to find our better nature. Four decades may have passed, but it’s not too late to prove Johnson right.