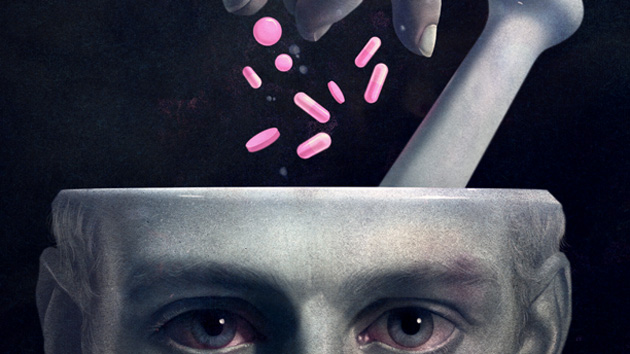

Illustration: Sam Weber

A DECADE AGO, when the inspector general of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) investigated (PDF) the recruitment practices of pharmaceutical trials, researchers complained that research sponsors were demanding unrealistically tight deadlines to enroll subjects. Asked by the IG what sponsors were looking for in trial sites, one researcher replied, “Number one—”rapid enrollment. Number two—”rapid enrollment. Number three—”rapid enrollment.” Many researchers attributed the unrelenting pressure to the fact that trials were being managed by businesspeople, not clinicians.

Over the past 20 years, medical research has become a largely privatized, and thoroughly Taylorized, business. Two-thirds of clinical trials are now privately run. Many trials are advertised by patient recruitment specialists, carried out by “contract researchers,” approved by for-profit ethics boards, and written up for publication by commercial medical education agencies. The largest of the new private industries are contract research organizations (CROs), which range from small niche agencies to multinational corporations that manage all aspects of clinical trials, from ethics approval and subject recruitment to the submission of clinical data to the FDA. Quintiles, the company that managed the study in which Dan Markingson was enrolled, is the largest, with 14 percent of the $11.4 billion global market.

CROs save money for pharmaceutical companies by deploying the principles of industrial management: breaking trials down into narrow, discrete steps, which can be carried out with maximum efficiency by specialized workers who can be paid relatively low wages. According to Vanderbilt University social scientist Jill Fisher, author of Medical Research for Hire, very little experience is required to be a cro “monitor” —a middle manager, often a nurse, who coordinates the various sites involved in a study. Monitors usually make less than their counterparts at universities or pharmaceutical companies, and job turnover is very rapid. Fisher says, “The goal of many monitors is to be hired by the pharmaceutical industry.”

In contrast, the private physicians paid to supervise clinical trials are often very well-compensated. A part-time contract researcher conducting four or five clinical trials a year can expect to earn an average of $300,000 in extra income. Yet they generally have little if any research training. They do not generate original scientific ideas, design studies, or analyze the results. Their main role is to help recruit subjects and oversee their trial participation.

Research subjects are the most highly prized commodities in the clinical trials industry. Four out of five clinical trials are delayed because of difficulties recruiting subjects. These delays can be costly, as the patent clock on new drugs starts ticking as soon as the patent is filed.

As CROs have discovered, many research subjects can be persuaded to enroll because they have no health insurance or because they are too poor to afford medication. (According to Fisher, a common CRO term for these patients is “ready-to-recruit.”) In the CAFE study, for instance, a Quintiles study monitor suggested that each of the CAFE study site coordinators try recruiting subjects at homeless shelters. Nevertheless, early on the University of Minnesota trial site was apparently struggling to keep subjects in the study. “Having trouble with Subject 002,” Jean Kenney, the university’s CAFE study coordinator, wrote in a January 2003 email to Quintiles. “His sister just died, his father has terminal cancer and now the grandmother is sick. He missed a visit and now just missed the next one.” Another issue was slow recruitment. “Have had another person show interest from inpatient and then the parent put pressure on and said ‘NO’ (third time this has happened),” Kenney wrote. The Quintiles study monitor was consistently upbeat and encouraging. “Try not to get too frustrated!” she advised. “Hopefully your hard work will start to pay off soon!”

Many CROs market their ability to locate subject populations that are “treatment-naïve,” meaning patients who have not yet been treated for their illness or who are not taking any other medications. Often treatment-naïve subjects are easier to find in poorer countries, where trials can also be conducted with less oversight from the FDA. In 2008, according to HHS, 78 percent of subjects enrolled in clinical trials lived outside the United States, including 13,000 subjects in Peru, where the FDA conducted no inspections. (PDF)

CROs have been involved in some notable clinical trial scandals. In the 1990s, Pharmaceutical Product Development, or PPD, one of the largest, was implicated in a notorious fraud scheme carried out by Dr. Robert Fiddes, who used his Southern California Research Institute to falsify records and invent patients while conducting trials for nearly every major pharmaceutical company. In 2006, at a trial site at a hospital near London, six healthy subjects nearly died after the CRO Parexel paid them 2,000 pounds each to become the first humans to test an experimental compound. In 2005, Bloomberg News reporters discovered (PDF) that SFBC International Inc. was paying undocumented immigrants to serve as drug guinea pigs in a converted Holiday Inn. The Miami motel was subsequently demolished for fire and safety violations, and the company changed its name to PharmaNet. In 2009, PharmaNet was acquired by JLL Partners, a New York hedge fund.

Today, if cash-strapped academic centers want to compete for the revenue generated by industry-sponsored trials, they must play by new rules. Academic institutional review boards must approve trials quickly to compete with for-profit IRBS (see “Poor Reviews“), and academic study coordinators must recruit subjects quickly to compete with private trial sites. The competition is even stiffer for academic physicians, many of whom must generate part of their own university salaries by obtaining grants and contracts from external funding sources. If academic physicians want to do clinical trials for the pharmaceutical industry, they must compete with contract researchers, who offer little to the body of science but carry out industry-tailored trials efficiently. Such arrangements often reduce academic physicians to little more than industry helpers, collecting data according to a company protocol. All these factors, it seems, were at play in the study that Dan Markingson was enrolled in when he died.