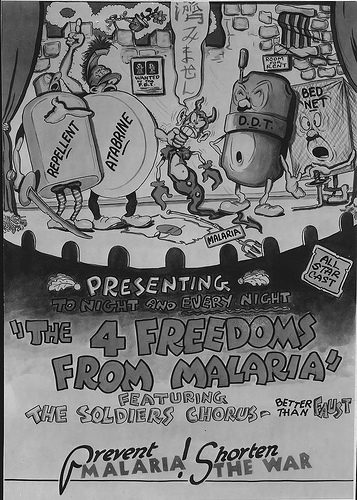

Illustration: David Goldin

In August 2009, a 34-year-old woman from Rochester, New York, went to her doctor complaining of flulike symptoms. The doc ordered some blood tests, which came back positive for dengue fever, a mosquito-borne virus that can cause serious illness and sometimes death—a baffling diagnosis, since the woman hadn’t recently traveled anyplace where dengue is endemic. She had, however, been to Key West, where, in the months that followed, more tourists and residents were diagnosed. Thus began Florida’s first significant dengue outbreak since 1934. Some scientists postulated that climate change has made the region more hospitable to Aedes aegypti, the primary species known to spread the virus.

The agency in charge of mosquito control for the Keys responded by blanketing the city with pesticides targeting both larvae and adult mosquitoes. Even so, the outbreak lasted for 15 months and sickened 93 people. While there hasn’t been a new case since November 2010, local leaders aren’t eager to relive the nightmare. And now they figure they won’t have to, thanks to a recent high-tech innovation: self-destructing mosquitoes.

These specialized skeeters, developed by the British company Oxitec, are genetically engineered to need the antibiotic tetracycline—common in the lab but scant in the wild—in order to survive past the larval stage. The altered males mate with wild females and presto: Lacking tetracycline to feed on, their offspring die before they’re old enough to bite.

So far, Oxitec has teamed up with local officials and released its critters in Brazil, Malaysia, and the Cayman Islands—where the company claims an 80 percent decline in the Aedes aegypti population over three months. Mosquito control wonks everywhere were impressed. Oxitec’s method can cost less than spraying, never mind the nasty chemicals: Key West would pay $200,000 to $400,000 a year for eggs versus $800,000 for the pesticides. Oxitec CEO Hadyn Parry, a former employee of the agribusiness giant Syngenta, sees his company’s product as a humanitarian triumph. “We want to make this as widely available as we can,” he says.

This February the company secured an investment of $13 million to expand its technology. “The success of our funding round,” proclaims Oxitec’s press release, “underlines the confidence investors from around the world have in our approach and its potential.” In a similar but separate project, scientists from the University of California-Irvine are testing out their own Aedes aegypti mutants, which are engineered to produce flightless offspring.

But not everyone is convinced that this sort of approach is a silver bullet. “This technology hasn’t been properly tested, nor is it clear that it’s going to work,” says Eric Hoffman, who tracks genetic engineering issues for the environmental group Friends of the Earth. “The public isn’t being told the whole truth.”

For starters, Hoffman says, no one quite knows what will happen to an ecosystem suddenly devoid of Aedes aegypti. Suppose a worse mosquito species takes over? Of particular concern is the so-called Asian tiger. One of the most invasive species in the world—and a potential dengue carrier—it breeds extremely rapidly and may require great quantities of pesticide to control. (Oxitec says it has an answer for that: Mutant Asian tigers are in the works, which raises the weird specter of an endless succession of engineered bloodsuckers.)

Then there are the offspring that don’t self-destruct. Oxitec admits that a small percentage of its altered mosquitoes, including biting females, can survive in the lab without tetracycline. Introducing any new engineered species into the wild, Hoffman says, brings up the possibility that we may be allergic to it.

CEO Parry says independent studies commissioned by his company suggest that allergens won’t be an issue. But maybe more to the point, he concedes that the company doesn’t know whether its method can reduce dengue over the long term. To date, the most important weapon against the disease has been public education. “When people are taught to police their own homes for potential breeding areas”—cisterns, kiddie pools, even old soda cans—”incidence of dengue decreases,” says Phil Lounibos, a medical entomologist at the University of Florida.

It’s troubling, then, that Oxitec doesn’t have a great track record when it comes to educating the locals about its bugs. In the Caymans, many people didn’t realize the firm’s mosquitoes had been released until after the fact. And it wasn’t until this March, after media reports had Key Westers riled up over the prospect of mutant skeeters, that mosquito control officials finally scheduled a public meeting with Oxitec in the house to answer questions. The same officials say they’re awaiting federal approval before actually unleashing any mosquitoes. The FDA won’t say how long that might take—only that it will review the scientific issues “rigorously.”

That’s one case of regulatory heel-dragging I can get behind.