Scientists have made great strides in predicting what will happen to Earth’s climate, but there is a fundamental problem: We only have one climate to test our hypotheses in. We can’t irreversibly hack Earth’s climate (by pumping it full of toxic gases, for example) to test whether our assumptions are right or wrong—that, obviously, would be disastrous for Earth’s inhabitants. That means climate models are loaded with historical and empirical data to make them function.

If only we could take the model to another planet to really test the underpinning physics.

Bingo. Curiosity, the car-sized mobile chemistry lab that dropped spectacularly onto the surface of Mars yesterday, will give scientists a rare chance to test their assumptions about how climate change works on Earth. It will hunt the surface of Mars for sediment to pick up and drop into its sophisticated onboard machinery, then send back critical insights into how the climate of Mars—once warmer, with rain, rivers, and deltas—has changed over billions of years, lashed by solar winds.

“You learn about how to understand an atmosphere by seeing different atmospheres,” said Mark Lemmon, a planetary scientist from Texas A&M University who is part of Curiosity‘s climate team. “And the more we know about Mars’ atmosphere, the better we can really understand our own.”

Curiosity allows scientists to “break the model,” he said. “We find out much, much more about our place in the universe than we could know just by contemplating ourselves.”

All with the latest bells and whistles: “We can remotely look at a rock with a laser beam, vaporize it, and see what elements are in it,” Lemmon said in a telephone interview from Pasadena, California, the morning after the historic landing.

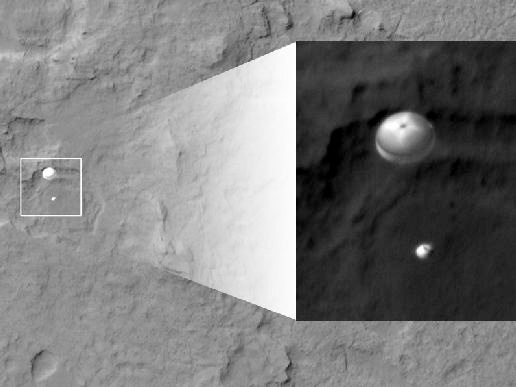

Curiosity Spotted on Parachute by Orbiter Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. of Arizona

Curiosity Spotted on Parachute by Orbiter Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. of Arizona

This has happened before, Lemmon explains. When scientists first ran Earth’s climate models against the climate of Venus, winds on Venus ground to a theoretical halt within days. Something in Earth’s modeling wasn’t accounting for how wind worked on that distant planet. By tinkering with new physics, scientists finally accommodated for Venus’ winds, thus reducing the margin of error in Earth’s climate models.

“Realistically, we cannot sit here on Earth and deliberately mess our climate in order to test the models,” Lemmon said. “And that’s what I think the real power of the climate part of the Mars program is all about.”

Specifically, Curiosity will study how carbon flows through the Martian world, something that will help scientists compare the two planets.

Paul Niles is also working with the NASA team. He is a planetary geologist and analytical geochemist at NASA’s Johnson Space Center who watched the touch-down with his family in Los Angeles.

“One of the things that Curiosity is going to help us learn much more about is…How does carbon cycle through the system? Where does it go? Where does it end up? Does it ever come back again? Is it ever buried deep enough that it come back again from volcanoes?”

Even though Mars’ atmosphere is completely different from Earth’s, the answers to these questions could shed light on how carbon cycles are now contributing to climate change on Earth. After initial rounds of analysis, “we might be in a better position to make direct comparisons with what happens on Earth,” Niles said.

Both Niles and Lemmon said that, with the dramatic landing complete, the real work has only just begun.

Lemmon texted one word to his wife from Pasadena when Curiosity kissed Mars’s surface for the first time: “Joy.”

“We know there’s stuff out there, and we need to see what it is!” he said.

“I think space exploration is a critical piece of pushing the boundaries,” Niles said. “The best part about it is it makes us address problems that we maybe wouldn’t have addressed, and solve problems we may have not solved otherwise.”