Nathanael Johnson

Free-range chickens, yoga, doulas, the paleo diet: They’re no longer just for hippies. The ’60s subculture that conservatives loved to hate is now about as controversial as motherhood and apple pie—especially if those apples aren’t organic. But is “natural living” always better? The son of two die-hard California hippies, Nathanael Johnson brings a critical take to his parents’ ideology in his new book, All Natural: A Skeptic’s Quest for Health and Happiness in an Age of Ecological Anxiety, which comes out this week. Think of him as Alex P. Keaton, but without the suits and Reagan fetish. In a face-to-face chat at Mother Jones HQ, we touched on modern medicine, raw milk, and when it’s safe to let your kids roll around in the dirt.

MJ: You write that when you were five, you suddenly realized you hadn’t been raised like everyone else.

NJ: We’d moved up to a new town in the mountains in California, and there was a lake where all these kids were swimming. I just stripped off all my clothes and swam out there. All of the kids look at me, and this little girl just shrieks, “He’s naked!”

MJ: In the book you call your parents “hippies.” What does that mean, exactly?

NJ: My parents were hippies of the “all natural” persuasion. They were interested in trying to find ways to live more in harmony with nature, to get away from the very busy work-driven style of life, and ways to be healthier by rejecting different forms of technology.

MJ: They fled Berkeley to go back to the land. And now you live in San Francisco, which is more urban than Berkeley. Do you ever think about returning to nature?

NJ: All the time, really. But I think it has less to do with fleeing back to nature than just missing my childhood home. While my parents felt like they could only go back to the land by leaving the city, I feel like you can go back to the land within the city. The land is still there, and nature is still there.

MJ: But why live in the city?

NJ: Culture, primarily. There’s lots of interesting people here, and interesting work, and interesting ideas circulating. Culture and nature are really intertwined, and I’m really interested in having both in my life.

MJ: You were born at home, but your daughter was born in the hospital. What do you and your wife have against natural childbirth?

NJ: I don’t have anything against natural childbirth, or home birth. In terms of whether it’s better or safer, it’s really a hard thing to study in a super objective way. So it’s sort of a Rorschach test: The interpretations that people bring to it say more about them than about the data. My wife just feels much more comfortable giving birth in the hospital.

MJ: In fact, you argue that being at ease during childbirth matters more than we may realize.

NJ: The theory is that, as humans evolved a smaller pelvis and bigger brains, we started seeking each other out for help during labor. We really became a social animal in some ways through the practice of obstetrics. The feelings of anxiety that come with birth prompt a laboring woman to find help. And there’s evidence that feelings of safety trigger hormones that then allow the cervix to relax and dilate, and then the baby to come through.

MJ: Though you and your wife chose the hospital, you also write about how modern medicine is in some ways making us sicker.

NJ: You hear a chorus of medical professionals saying that we are providing way more medicine than necessary and it is starting to do more harm than good. Shock during birth has more than doubled in the last decade. Renal failure went up 97 percent. The answer has to do with better communication and shared decision-making between the patient and the doctor. But the doctors are often incentivized not to do this: They are paid less if the patient ends up opting out of treatment.

MJ: How are you dealing with the flu epidemic?

NJ: I got a flu shot for the first time this year. I wasn’t one of those people who thought that vaccines were evil, but my basic tendency of medical nihilism just made me resistant to the idea. I came around because I did a lot of research and checked out every fear that I had heard about, and I was amazed that every single one of those things led back to the conclusion that there wasn’t anything to worry about.

MJ: Hippies tell us that germs are good. That rolling around in dirt makes kids healthier.

NJ: The science still hasn’t pinned down what kind of dirt you need to roll around in, but we have evolved in this soup of microbial life and some of that life has gotten incorporated into the way our bodies function. We have systematically been removing ourselves from that and protecting ourselves from it, to great effect: Infectious diseases have gone way, way down. But we have also seen some problems cropping up around autoimmune diseases—asthma, allergies, eczema. It’s still a hypothesis that wiping out beneficial microbes is to blame for this, but it’s worth taking seriously.

MJ: So at what point do you as a parent start worrying about the things that your daughter puts in her mouth?

NJ: Well, this is the trick. I talk a lot about two perspectives in the book: the technological perspective that is very narrow and good at getting the details right, and this more natural perspective that is good at talking about big ideas. You need this technological perspective to come back in and tell us which of these microbial friends we want. Or if it’s okay for my daughter to pick up a bottle cap from the sidewalk and put it in her mouth. With this one I feel like I’m left pretty much like any other adult. I feel like its okay if she plays with grass even though a dog might have walked over it, but then if it’s a cigarette butt I’ll knock it out of her hand pretty quickly.

MJ: The bacteria in raw milk are supposed to be good for us. Do you drink it?

NJ: I do. The bigger reason has more to do with wanting to support the type of agriculture that produces that milk.

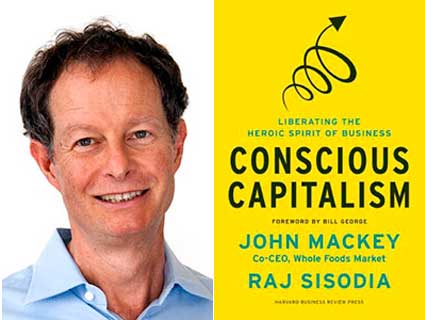

MJ: How is that agriculture necessarily different from the organic milk you get at Whole Foods?

NJ: It’s not necessarily different. There are raw milk dairies that have their animals in horrible conditions, but the dairy where I was getting my milk from is an idyllic place. It’s just more of what I would like the world to look like.

MJ: You grew up eating a paleo diet, which is much more mainstream today that it was back then. Is it a good idea?

NJ: This is one of the many issues where I feel like there is a kernel of truth and then people take it to crazy places. For example, while I was up at my parents’ place over Christmas, my dad had this new paleo diet book. The recipes looked really good, and healthy. But then I keep flipping and I get to the paleo brownies with bacon. And the justification is that they are made with all ingredients that a cave man theoretically could get his hands on: The flour is coconut flour, and the sugar is from dates, and I guess you could stab a wild boar for the bacon. So there is this tendency to move away from the spirit of the rule, which makes a lot of sense, to the letter of the law, which can be abstracted and taken to these crazy places.

MJ: Are you still a devotee of paleo eating?

NJ: No, I am not. The other issue is that humans have evolved. Milk is a good example. My ancestors developed the mutation to be able to digest lactose. I think diet has to be more of a cultural tinkering process where you figure out what works for you and what keeps you healthy.

MJ: What is the biggest environmental conundrum for you?

NJ: Air travel, because that’s where the C02 footprint for most of us really leaps.

MJ: What do you feel the most guilty about?

NJ: I have moved away from feeling guilt. As a teenager, I felt guilty all the time. At some point I realized that I could be as responsible as I wanted to be—so responsible that I ended up living out in a shack in the woods—and that someone else would wipe out all my good works in one day with their personal Learjet.

MJ: Garret Hardin’s “tragedy of the commons.”

NJ: Exactly. I think the solutions really have to be community-wide, nationwide, worldwide—regulating the use of these resources for everyone.

MJ: If that’s the case, then why bother to research which raw milk farmer you should support?

NJ: It’s less about my personal feeling of guilt and more about a feeling of contentment and satisfaction in the way that I am living my own life. In some ways, that milk tastes a little better to me when I can imagine the place that it comes from. And it makes me feel good that I can see a path forward through these actions that I am taking. If people used that incentive to then go out and legislate, we could solve some of these problems.

MJ: Compared to your parents, do you think that you have a smaller ecological footprint?

NJ: I probably do. It would be close. They might have flown a little less than I do. But because I live in the city and I don’t have a car, I burn a lot less gasoline. Growing up in the country, it was fairly routine to drive an hour and a half to visit a friend or go to a soccer game.

MJ: So that’s progress.

NJ: Yeah. I came away from writing this book feeling very slightly more hopeful than when I went into it. My parents felt like they had to completely abandon the civilization that we were living in and call for revolution or just start over. To me, that feels hopeless because obviously they didn’t win. You feel like this outsider while there is this huge behemoth just moving forward. I feel like I can organize in my own little community. I can do the hard, boring, frustrating work of politics locally and make these tiny incremental changes. That is not a lot of hope. It’s a really tough thing to do. But if feels slightly more hopeful than just, “Screw it all. We’re moving to Alaska.”