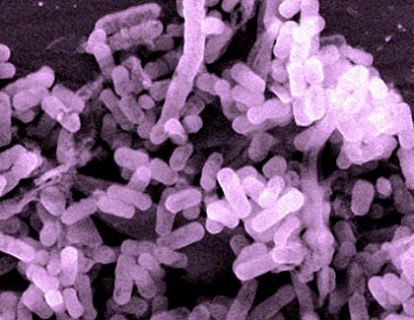

A strain of Lactobacillus plantarum (with false color)Dr. Rani Menon and Ann Ellis/Texas A&M Imaging and Microscopy Center

A few years ago, after a gnarly bout of giardia earned from a few months studying in India, and the ensuing rounds of antibiotics prescribed to kill the bugs, I began to take a probiotic supplement to recoup. I was hoping for something to help me digest, and for some new microorganisms to repopulate my intestine and fend off bad bacteria. The regimen was easy—right before breakfast, I’d down one or two small capsules with some water. And it seemed to work; within a few months, my digestion was back on track. But it’s a little hard to say: Did the probiotics cure my turbulent gut, or was it just the passage of time and a return to normal food and sanitation?

The human GI tract contains more than 500 species of bacteria that help break down food, strengthen immunity, and ward off pathogens. This community of trillions of microbes together weighs up to 2.2 pounds and its cells outnumber human cells 10-to-1. “There’s a war going on in your gut,” says gastroenterologist Dr. Shekhar Challa, author of Probiotics for Dummies and coproducer of Microwarriors: The Battle Within, a video game about probiotics. When the ratio of good to bad bacteria gets out of whack, he says, adding a probiotic—a beneficial bacteria—can help refuel the good guys. Lactobacillus acidophilus, found in some yogurt, is probably the best-known strain. These microbes bind to the lining of the gut, help you digest, battle toxic intruders, and can stimulate the immune system. They’ve also been credited—though with varying levels of evidence—with preventing or curing diarrhea, gastrointestinal diseases, yeast infections, and allergies.

One recent study even indicates that probiotics could be used to regulate emotions and mitigate depression via their effect on neurotransmitters. (Radiolab fans might remember this from the episode “Guts.”) Researchers in Ireland found that mice treated with Lactobacillus rhamnosus suffered less stress, anxiety, and depression-related behavior, suggesting that certain strains of probiotics could one day be used to treat those symptoms in humans.

The excitement about probiotics’ potential has prompted a slew of pills, drinks, and super-yogurts promising to “help regulate your digestive system” (Dannon Activia), “balance bacteria in your gut” (Good Belly), and support “immune health” (Culturelle). Even after Dannon was sued in 2010 for deceptive advertising about its probiotic-boosted yogurt products, including Activia (it settled but never admitted to wrongdoing), and Europe cracked down on claims made by the probiotic industry, fortified food and drink sales have stayed strong—and are blossoming in Asia. (Global probiotic sales are expected to jump from $28 billion in 2011 to $42 billion in 2016.) The supplements can be costly, often $1 a pill or serving. Though they aren’t regulated as drugs by the FDA, the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization considers probiotics “live microorganisms” that can “confer a health benefit on the host.” But many scientists and physicians still have doubts about whether probiotic supplements have much effect, especially since relatively little clinical research has been done to test them.

And like other supplements, when it comes to the supposed health benefits, caveats abound. The vigor of a probiotic in part depends on the quantity of colony-forming units (CFUs) present. “You should be getting 3-5 billion CFUs a day,” advises Challa. “95 percent of probiotic supplements, you can send them out to testing and I promise you they won’t have 10 percent of the CFUs they say they have.”

ConsumerLab.com did just that. When the agency tested 12 popular brands sold in the United States, two—Nutrition Now PB8 and i-Flora Kids Multi-Probiotic—contained only 56.8 percent and 65 percent, respectively, of the cells claimed on the label, though the other 10 contained the amounts advertised. “Like any supplement, it’s kind of a buyer-beware situation,” says ConsumerLabs’ president, Tod Cooperman. “There really aren’t a lot of rules from the FDA on how the products are tested.” Many probiotics require refrigeration, and sometimes they aren’t kept cold during transit or on the shelves of unknowing shopkeepers. Beware of probiotics bought online, warns Cooperman. “The manufacturer should offer to send it to you refrigerated.”

And not all probiotics are right for all conditions. “You can kind of think of probiotics as more or less a toolbox,” says Joseph Sturino, an assistant professor in Texas A&M University’s food and nutrition department who’s studying the interactions between probiotics and pathogens. “Some strains are going to be really good at doing one thing, and others are going to be good at doing another.” (For a breakdown of certain probiotic strains linked to alleviating conditions like antibiotic associated diarrhea, see ConsumerLab’s report or “A Gastroenterologist’s Guide to Probiotics.”) But most importantly, cautions Sturino, for any serious condition, probiotics should be taken upon the referral of a physician. “You really want to see good clinical trials with good efficacy for the condition you’re interested in,” he says.

What’s more, noted the experts I spoke to, most probiotics you take as supplements won’t actually colonize your gut, so any effect will be temporary, and won’t compare to the work of a healthy microbiome. The few dozen strains that are commercially available, says Moises Velasquez-Manoff, author of MoJo‘s “Are Happy Gut Bacteria Key to Weight Loss?,” “are a pittance compared to the 1,000 species within. What you’d really want is to get microbes native to the gut and replenish them. We haven’t figured out which ones are the right ones or how to implant them.”

We may see improvements as scientists start to piece together what they know about probiotics and prebiotics, those indigestible fibers that serve as food for probiotics and our inherent microbes (see “Are Happy Gut Bacteria…” for more on prebiotics) and that already come to us via much of the food we eat. (Green vegetables, Jerusalem artichokes, oatmeal, and legumes are particularly rich in them.) To find prebiotics in supplements, look on the label for added FOS, or fructooligosaccharides. You can also find synbiotics, combinations of complimentary pro- and prebiotics. Since these prebiotics feed microorganisms, probiotic products that contain them, claims Challa, may give you “a one-two punch.” But Cooperman of ConsumerLab wasn’t so sure. “You’re only getting what, a gram or two a pill?” he says, referring to prebiotics. “How much can that help you compared to eating lunch?”

Ah, lunch. I hadn’t explored much about the probiotics and prebiotics that occur naturally in food until I spoke with Sandor Ellix Katz, author of Wild Fermentation and a guy who introduces himself these days as a “fermentation revivalist.” Raw, unpasteurized fermented foods like sauerkraut, sour pickles, and kimchi are naturally high in good bacteria, as are some yogurts, kefirs, and stinky cheeses. “People in the probiotics industry have largely scoffed at the idea that traditional foods could give you the same benefits,” Katz says. “Frankly, nobody’s doing clinical trials for sauerkraut.” Cultured foods can come with hundreds of diverse strains of bacteria and yeast, the number of microbes multiplying as the stages of fermentation evolve. Plus, these foods come with the added benefit of vitamins and nutrients. “Bacteria are not fixed,” Katz says. “To me, that’s the flaw with the probiotic idea. It seems like diverse bacterial stimulation will always be better than a single strain.”

That’s not to say you should switch to an all-kimchi diet: Fermented foods can be super salty, and they’ve been subject to little scientific study. But incorporating cultured foods into a well-balanced diet, complemented by plenty of prebiotic-laden foods, might come with the same digestive and immune benefits as a capsule, and a tastier experience to boot.