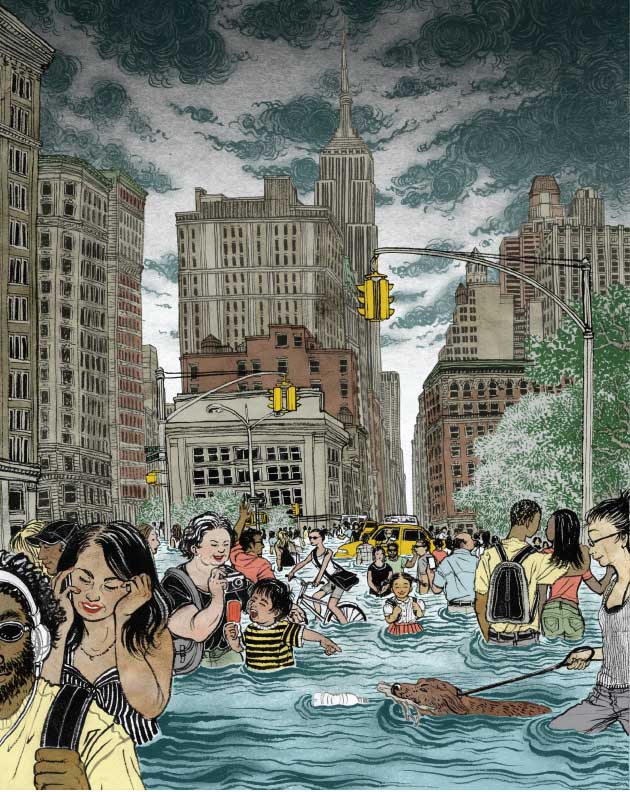

Illustration by Yuko Shimizu

Two months after Hurricane Sandy pummeled New York City, Battery Park is again humming with tourists and hustlers, guys selling foam Statue of Liberty crowns, and commuters shuffling off the Staten Island Ferry. On a winter day when the bright sun takes the edge off a frigid harbor breeze, it’s hard to imagine all this under water. But if you look closely, there are hints that not everything is back to normal.

Take the boarded-up entrance to the new South Ferry subway station at the end of the No. 1 line. The metal structure covering the stairwell is dotted with rust and streaked with salt, tracing the high-water mark at 13.88 feet above the low-tide line—a level that surpassed all historical floods by nearly four feet. The saltwater submerged the station, turning it into a “large fish tank,” as former Metropolitan Transportation Authority Chairman Joseph Lhota put it, corroding the signals and ruining the interior. While the city reopened the old station in early April, the newer one is expected to remain closed to the public for as long as three years.

Before the storm, South Ferry was easily one of the more extravagant stations in the city, refurbished to the tune of $545 million in 2009 and praised by former MTA CEO Elliot Sander as “artistically beautiful and highly functional.” Just three years later, the city is poised to spend more than that amount fixing it. Some have argued that South Ferry shouldn’t be reopened at all.

The destruction in Battery Park could be seen as simple misfortune: After all, city planners couldn’t have known that within a few years the beautiful new station would be submerged in the most destructive storm to ever hit New York City.

Except for one thing: They sort of did know. Back in February 2009, a month before the station was unveiled, a major report from the New York City Panel on Climate Change—which Mayor Michael Bloomberg convened to inform the city’s climate adaptation planning—warned that global warming and sea level rise were increasing the likelihood that New York City would be paralyzed by major flooding. “Of course it flooded,” said George Deodatis, a civil engineer at Columbia University. “They spent a lot of money, but they didn’t put in any floodgates or any protection.”

And it wasn’t just one warning. Eight years before the Panel on Climate Change’s report, an assessment of global warming’s impacts in New York City had also cautioned of potential flooding. “Basically pretty much everything that we projected happened,” says Cynthia Rosenzweig, a senior research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, co-chair of the Panel on Climate Change, and the coÂauthor of that 2001 report.

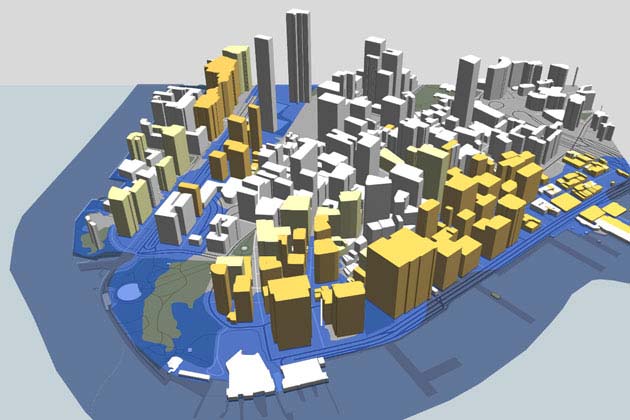

Scientists often refer to the “100-year flood,” the highest water level expected over the course of a century. But with sea levels rising along the East Coast—a natural phenomenon accelerated by climate change—scientists project that in our lifetimes what was once considered a 100-year flood will happen every 3 to 20 years. And truly catastrophic storms will do damage unimaginable today. “With the exact same Sandy 100 years from now,” Deodatis says, “if you have, say, five feet of sea level rise, it’s going to be much more devastating.”

Roughly 123 million of us—39 percent of the US population—dwell in coastal counties. And that spells trouble: 50 percent of the nation’s shorelines, 11,200 miles in all, are highly vulnerable to sea level rise, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. And the problem isn’t so much that the surf laps a few inches higher: It’s what happens to all that extra water during a storm.

We’re already getting a taste of what this will mean. Hurricane Sandy is expected to cost the federal government $60 billion. Over the past three years, 10 other storms have each caused more than $1 billion in damage. In 2011, the federal government declared a record 94 weather-related major disasters, from hurricanes to wildfires*. The United States averaged 56 such disasters per year from 2000 to 2010, and a mere 18 a year in the 1960s.

The consequences for the federal budget are staggering. In just the past two years, natural disasters have cost the Treasury $188 billion—nearly $2 billion a week. The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), which covers more than $1 trillion in assets, is one of the nation’s largest fiscal liabilities. The program went $16 billion in the hole on Hurricane Katrina, and after Sandy it will be at least $25 billion in debt—a deficit unlikely ever to be fixed.

Meanwhile, Washington is stuck in an endless cycle of disaster response. The US government spends billions of dollars on disasters after they happen, but it pinches pennies when it comes to preparing for them. And both federal and state policies create incentives for people to build and rebuild in increasingly risky coastal areas. “The large fiscal machinery at the federal level is cranking ahead as if there’s no sea level rise, and as if Sandy never happened,” says David Conrad, a water consultant who has been working on flood policy for decades. “This issue is moving so much faster than the governmental apparatus right now.”

Put another way: We’re already deep under water.

How likely is another superstorm?

Odds that New York City will see flooding like Sandy’s again next year are 1 in 10,000. But if scientists’ worst-case sea level predictions hold, by 2100 those odds will be 1 in 2. For coastal Virginia, odds of flooding like Hurricane Isabel’s are 1 in 100 right now. By 2060, another Isabel could happen every single year.

Some 350 miles south of the South Ferry subway station, on Virginia’s Middle Peninsula, is Gloucester County. The red-brick homes and matching sidewalks give the county seat, Gloucester Courthouse, a colonial feel. The county was the site of Werowocomoco, the capital of the Powhatan Confederacy, and just across the York River to the southwest are Jamestown, Yorktown, and Williamsburg, some of the earliest English settlements in North America. Europeans first settled the county in 1651, and some local families date back just about that far. In the more remote necks on the bay, watermen still speak Guinean, a dialect full of “ye” and other archaic words along with the lilt of dropped r’s and d’s of the greater Tidewater area.

Gloucester County’s population of 36,886 is spread over 217 square miles, with a median household income of $62,000. Historically, most in the region relied on fishing and agriculture, but now many commute over the George P. Coleman Memorial Bridge to Williamsburg and Norfolk. A few McMansions have popped up, but they look out of place; I saw one fancy house sitting next to a trailer with a goat roped to the front porch.

Gloucester is one of the biggest losers in the geographic lottery when it comes to sea level rise—low, surrounded by water, and flat as a billiard table. In 2003, Hurricane Isabel walloped the county, causing $1.9 billion in damage throughout the state of Virginia. And that was just the beginning.

On a warmer-than-it-should-be spring morning, I meet Chris West, a burly tugboat engineer whose gray rancher sits about 120 yards from the Severn River and about three feet above sea level. He’s in his driveway, waiting for a team of contractors to jack his home six feet up in the air. West’s parents built the house 60 years ago, and he’s lived there his whole life.

West, 43, watches as the contractors clear brush and unhook his utilities; soon they will break the foundation, shove giant wooden beams under the house, and crank it up on hydraulic jacks. Then they will stack four wooden piers beneath the structure, like Lincoln Logs, to hold it up as they pour cement for a new foundation six feet higher. West and his dogs will stay at his girlfriend’s house while the house is under construction.

“I got butterflies,” he says.

Raising up the house would have cost West $85,000, but it’s being subsidized by the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, so he only has to cover around $4,000. So far, FEMA has given Gloucester County $11.8 million to raise 60 homes, and another 59 homes and businesses are in line for a lift. The county also offers residents an outright buyout, but only 17 families and one business have gone that route.

What was once a 100-year flood will happen every 3 to 20 years. And truly catastrophic storms will do damage unimaginable today.

Neither FEMA nor county officials promote the grants as a climate change adaptation program—even if that’s exactly what they are becoming. “Even the naysayers have noticed the increased number of storms,” says Anne Ducey-Ortiz, Gloucester’s director of planning. “Even when people don’t want to deal with climate change, they are willing to talk about increased flooding.”

For West, the reality hit home during Hurricane Isabel. The storm pushed water from the Chesapeake Bay into the Mobjack Bay, then up into the Severn, through his backyard, over the deck, and into the house. He had 18 inches of seawater inside and nearly $30,000 in damage. He spent three and a half months living with his in-laws as he tore out drywall and carpets and replaced all his furniture.

Isabel was the worst storm in this region as far back as most people here can remember, and folks assumed the next one wouldn’t come for a long while. “You think, ‘Thirty more years I won’t be living here anyhow, I’ll be in a nursing home,'” West says. But then just three years later, a tropical storm named Ernesto blew through, bringing the water an inch and a half short of his deck. Then there was Nor’Ida in November 2009, and Hurricane Irene in August 2011, again bringing the water under the deck and inches below the threshold of his back door. Even the average tides behind the house, West reckons, seem almost a foot and a half higher than they used to be.

Tide measurements have found that the sea level along this part of Virginia’s southern coast has risen 14.5 inches in the past 80 years, and scientists expect the rate of increase to double for the rest of this century, adding another 27.2 inches. Meanwhile, the land is getting lower: The earth here has been settling due to the double whammy of a glacial retreat in the Pleistocene era 20,000 years ago and a giant meteor that hit some 35 million years before that. Removing massive amounts of groundwater for paper mills and other industrial uses has aggravated the sinking, much like the aquifer depletion that’s been causing killer sinkholes in Florida. The upshot, says Pam Mason, a senior coastal management scientist at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science in Gloucester: “You take our little two-foot tide and you put one more foot on it, and it starts to make a difference. We’ve gotten complacent. We’ve gotten really close to the edge.”

Ducey-Ortiz says that in a number of areas the county would prefer just to buy out homeowners because, even if you lift up the houses, flooding will submerge the roads, trapping residents and cutting off emergency services. Still, authorities won’t force anyone to move. “You’re allowing people to stay in a hazard area,” she acknowledges. But “in Gloucester, that’s our heritage, that whole Guinea area. To abandon those people, those families that live out there, people who just love living on the water—we want to help them.”

West says he might have considered taking a buyout, but it would have had to be at least $200,000—what he owes on his mortgage right now. Like most in Gloucester, he elected to stay. “It’s hard to take people out of their home, their true home,” he says. Most of his neighbors, “the only time they’ve left has been in a pine box.”

Perhaps the only topic touchier than whether people should abandon their homes is why the problem even exists. West has heard of global warming, but he’s not entirely sure it’s responsible for the rising water. “Nobody knows, I don’t think. Everybody speculates,” he says. Local authorities rarely, if ever, speak the words “climate change.”

“I wouldn’t want to turn some positive influences off by coming up with a political term,” said Paul Koll, Gloucester County’s building official. “I am really conscious of not labeling it anything so I don’t shoot myself in the foot.” Two years ago, when leaders in neighboring Mathews County broached the subject of sea level rise, tea partiers packed meetings warning of an environmentalist plot to “put nature above man.” They linked a proposal to build dikes to a United Nations sustainability plan known as Agenda 21, which has inspired a number of conspiracy theories among far-right activists.

Never mind that the Middle Peninsula, made up of Gloucester and five other counties, expects up to $249 million in new climate-related costs by 2050, a figure that doesn’t even include potential damage from storms like Isabel or Ida. The American Security Project, a Washington think tank, projects that climate impacts could cost the state a whopping $45.4 billion by 2050, with extreme storms alone putting $129.7 billion worth of property at risk.

Yet Republican Gov. Bob McDonnell phased out a Governor’s Commission on Climate Change after taking office in 2010. His attorney general, Ken Cuccinelli (who won the state’s Republican gubernatorial nomination in May), has spent a good deal of his time in office seeking to prosecute former University of Virginia climate scientist Michael Mann for his work on historic temperature records. And when state lawmakers requested a study on sea level rise, Republican state Del. Chris Stolle retorted that the term was “left-wing.” (The Legislature settled on “recurrent coastal flooding.”) And Virginia is better off than neighboring North Carolina, where lawmakers last year explicitly refused to consider scientists’ current projections in coastal building decisions.

*Correction: The original version of this article classified more of these disasters as weather-related; as one reader pointed out, four of them were instead earthquake-related.

Sunk costs: THe high prices of superstorms

Just as New York City planners had data showing that a superstorm could devastate the city, the federal government has plenty of data on the climate cliff—the looming budgetary catastrophe from emergency spending. In January, the National Climate Assessment and Development Advisory Committee released a draft of its latest report, warning of the “high vulnerability of coasts to climate change.” The report optimistically added that “proactively managing the risks will reduce costs over time.” But with congressional Republicans actively derisive of climate science, the odds of that are not great.

The closest thing to a federal effort to mitigate climate risk may be the 25-year-old FEMA grant program that pays for the house raisings in Virginia. But most of the money is designed to kick in after a disaster, to prevent recurrence—and it doesn’t take into account whether houses in the floodplain are viable in the long term. Still, it’s more proactive than the lion’s share of FEMA’s post-disaster spending, which allows people to rebuild in high-risk areas as if a storm or flood will never happen again.

I visited Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) in his office the day after the $60 billion Sandy relief package passed the House, nearly three months after the storm. He wasn’t happy with it. “What Sandy illustrated is both the increasing vulnerability—and the costs and consequences,” he told me. “But we really didn’t condition the recovery on making sure that we minimize people going back in harm’s way.”

A slight, bookish lawmaker whose lapel often sports a bright plastic bike pin, Blumenauer has been Congress’ loudest critic of disaster policy. Even the Sandy package, he notes, had no incentives to consider climate change as part of rebuilding plans. If Blumenauer had his way, the federal government wouldn’t rebuild any of its facilities in the floodplain—no post offices, no office buildings. Counties that get disaster relief would be required to enforce better building and zoning codes. And the feds wouldn’t pay to keep rebuilding homes exactly as they were before a storm.

“In the aftermath of a disaster, the instinct is to reach out to people, to try to help them,” he adds. “And so many people, their first instinct is to just go right back. It is devastating to look at all the things we do that keep people anchored in very dangerous places.”

True, he says, it’s hard to challenge people’s yearning to rebuild. But at some point, lawmakers need to start thinking about the next cataclysm. “Before the next big wildfire, before part of the coast washes away, before the predictable unpredictable storm hits, what are the principles we’re going to have?” Blumenauer asks. “What is going to be the condition of federal assistance?” With that in mind, he has been trying to expand mitigation programs for years, with limited success. Under the 1988 Stafford Act, 15 percent of the emergency relief funding Congress allocates to FEMA must be used for mitigation, but that money is only allocated after disaster strikes.

I asked Blumenauer if it’s even practical, in the long run, to raise or relocate all of the homes that need it. “It’s expensive,” he says, “but it’s a fraction of what we’re routinely spending.”

Why, then, do we keep spending more? One reason is that most disaster spending doesn’t actually show up in the federal budget; it’s treated as “emergency spending,” which isn’t included in regular appropriations. So while fiscal hawks in Congress leave disaster preparedness programs chronically underfunded, disaster relief is treated as a budget freebie. The obsession with deficit reduction—codified in the 2011 Budget Control Act, which capped federal spending as part of the debt ceiling debate—has reinforced that trend. “You lowball it so you can spend the money elsewhere, but then you come in with the disaster supplemental, which is free money,” Blumenauer says. Congress has had to pencil in extra funding for FEMA’s Disaster Relief Fund in 8 of the last 10 years, after the appropriated amount fell short of the actual need. And it keeps happening; the Obama administration’s proposed 2013 budget, for example, shaved 3 percent—$1 billion—off the Disaster Relief Fund.

Chronically underfunding disaster spending is shortsighted in the extreme, says Blumenauer. “We’re just cannibalizing programs,” he says. “We save arguably $5 for each dollar we invest.”

Just as disaster relief funding ignores the fact that today’s disasters are tomorrow’s normal, the NFIP is virtually designed to ignore dramatic changes in weather and flood patterns. Created in 1968, it was made to help people in the most flood-prone areas acquire insurance—policies that private insurers were not willing to underwrite. In 1973, flood insurance was made mandatory for anyone who had a federally backed mortgage in an area considered at risk for a 100-year flood; those already living in those areas were grandfathered in at heavily subsidized rates. Today, the Property Casualty Insurers Association of America estimates that homeowners covered by federal flood insurance pay just half of the “true-risk cost” to insure their properties. In the highest-risk areas, they pay just a third.

No surprise, then, that the federal insurance program is now $25 billion in the hole. In the Sandy supplemental spending bill, Congress upped the program’s borrowing authority by $9.7 billion, to $30.4 billion, to meet new claims—money that is unlikely ever to be paid back. And because the subsidy is so great, there’s no incentive for private insurers to enter the market, says Frank Nutter, president of the trade group Reinsurance Association of America. “If you had a program that is fiscally sound, you’d probably find more insurance companies willing to write the risk,” he says. “They wouldn’t be competing with a government program that is underpricing the risk.”

The other problem with subsidized insurance is that it encourages people to build—and stay—in high-risk areas, since they’ll be bailed out even if they incur disaster after disaster. It’s what economists call a moral hazard, a circumstance that encourages people to engage in risky behavior because the costs are borne by others.

“In many cases,” says water consultant Conrad, “we’ve removed the most important element in our marketplace that forces the responsibility on the decision maker him- or herself.” Conrad has been documenting the flood insurance program’s problems since 1992. In 1998 he found that “repetitive loss” properties—those that had more than $1,000 worth of damages from a storm two or more times in a 10-year period—made up 2 percent of insured properties but were responsible for 40 percent of what the program was paying out. For 1 in 10 of those properties, the program had paid claims that totaled more than the house’s market value. (In response, in 1999 Blumenauer introduced the “Two Floods and You’re Out of the Taxpayers’ Pocket Act,” which never made it out of committee.)

The NFIP has long been a sore spot for both environmentalists and small-government conservatives. “It has been a very long-term subsidy for development in places where we simply shouldn’t be developing at all,” says Eli Lehrer, president of R Street, a libertarian think tank based in Washington. “There are areas that we’ve developed that probably shouldn’t have been developed in the first place, and wouldn’t have been if we had private insurance, or even actuarial rates in a public program.” But reform has been tough—because every attempt at change meets firm opposition from politicians representing flood-prone districts, and from local governments that rely on coastal properties for property taxes and economic development. “Every time they’d try to raise the rate, there would be a roar from up on Capitol Hill,” says Conrad.

In 2004, Blumenauer did push through a major overhaul of the insurance program, including incentives to raise or buy out houses that had been damaged multiple times. But it took hurricanes Rita and Katrina, and a more deficit-minded Congress, to pass another flood insurance reform bill last year that finally limited subsidies for second homes and for properties that were damaged repeatedly.

Under that 2012 reform, such homes will see premiums rise dramatically over the next five years, eventually bringing 400,000 of the most heavily subsidized properties up to market rates. The new law also lets FEMA buy homes that are considered “severe repetitive losses” at their full pre-disaster price, rather than the 75 percent it offered before.

But perhaps the most significant change in the reform involved maps—specifically, FEMA’s floodplain maps, which determine who must buy flood insurance. Those maps can now for the first time include “future changes in sea levels, precipitation, and intensity of hurricanes.” But there’s a catch: Those changes don’t affect the new flood maps FEMA is currently releasing, the first in 30 years. Floodplain maps issued for New York City and coastal New Jersey in late 2012 and early 2013, for example, don’t account for sea level rise. Maps for the rest of the country are rolling out slowly, and it’s unclear when they will start including sea level projections.

Back during the Bush administration, in 2007, FEMA began a major assessment of how climate change would affect the flood insurance program, with a projected completion date of 2010. When FEMA finally released the report in June 2013, it included a number of alarming findings. Rising seas and severe weather are expected to increase the area of the United States at risk of floods by up to 45 percent by 2100, doubling the number of people insured by an already insolvent program.

It took three and a half months to put Chris West’s house up on a higher foundation. When Hurricane Sandy glanced off the Virginia coast just a few months after the contractors were done, everything at his end of the neck flooded, but the water flowed right underneath his house. “I don’t have that worry anymore,” West says, “of being displaced out of my home.” A couple of other homeowners decided that they just wanted to leave; as of May, Gloucester County had acquired 18 parcels of land, but since then, eight more homeowners have signed up for buyouts.

As vulnerable as it is to rising seas, Gloucester is lucky. It has forward-thinking local officials who acknowledge the problem, even if they’d prefer not to talk about the root causes. Gloucester County has earned improving marks from FEMA for trying to minimize flood risks with steps like establishing tougher building codes and requiring all new development to be built at least two feet above flood height. Those initiatives lower the cost of insurance for homeowners, but they also save the federal government money—an estimated $4 in future savings on property damage alone for every dollar spent on prevention.

Skip Stiles hopes an appeal to fiscal sanity is what will finally get decision makers to care about climate. Stiles, 63, is the director of Wetlands Watch, a Norfolk-based advocacy group that formed back in 1999 to protect shoreline habitats. Not long after joining the group in 2005, Stiles realized that saving tiny parcels of marsh wasn’t going to help much if the entire coast was wiped out by century’s end. “We started realizing it’s not just the wetlands—it’s the whole freaking economy in this region that’s at risk,” he says.

That, and not that many people care about wetlands. “We said, ‘What do people care about?’ Their homes, their business, their way of life.”

Stiles took me on a ride through Norfolk, highlighting spots that have seen major flooding in the past few years. He pointed to one house where a car floated into the front door during a storm, and another that the owner, tired of dealing with the water, has been trying to sell for months. We drove through the Old Dominion University campus, where a small, permanent lake has formed in the back corner of a huge parking lot. “You can’t pave under water,” he noted dryly, “so this obviously wasn’t under water when this parking lot was paved.”

Stiles left Washington for coastal Virginia after 22 years as chief of staff to the late California Democratic Rep. George Brown, who in 1978 launched the first federal climate change research program. But it was not until he saw Norfolk’s frequent flooding that he realized climate change, far from a distant threat, was a disaster well under way. “I thought, ‘Oh, the feds are going to fix this,'” Stiles says. “BS, ain’t happening. It’s local government—and man, the politics at the local level.”

So Stiles started showing up at local planning commission meetings, begging officials to stop approving new shoreline developments in the face of inevitable sea level rise. Back when he began, in 2006, “they looked at us like we were crazy”—coastal land is often the most valuable in a county, and it generates the highest property taxes. But then he stopped talking about climate change and started talking about budgets. “Suddenly it was like a key in the lock,” he says. “What quickly happens is the money you put into those neighborhoods exceeds the property tax you get out. These neighborhoods turn into money pits. There just isn’t enough money to raise all of the structures that need to be raised.”

For Stiles, it doesn’t matter whether local officials will actually utter the words “climate change,” so long as they start dealing with the impacts. “Our perspective is just, ‘Look, get on the bus, and we’ll figure out together where the destination is,'” he says.

It’s all about good, old-fashioned fiscal conservatism, says Conrad, the water consultant: “If this is all done by just pots of money being thrown around, most of the residents will be inclined to just take the money, do what’s immediately convenient, and ignore the elephant in the room, which is that the Atlantic Ocean wants to move inland.”

Matthias Ruth, an economist at Northeastern University who focuses on climate impacts, says the key is to provide a financial return for planning ahead. “We know that what once was the 100-year floodplain now is the 10- or 5-year floodplain. So what we need to do is give the incentives to either fortify buildings, elevate them, flood-proof them, or have a controlled retreat.” Instead, “we pretend it’s not an issue and we put ever more infrastructure into the coasts and ever more people.”

Ruth ticks off the expected costs of climate change on the coasts—seawalls, flood insurance claims, disaster response, not to mention dislocation, stress on communities, and lost social connections. And what if, after a major storm like Sandy, there were an ice storm or maybe another hurricane the following year? “It’s these one-two punches, the cumulative effect that they have on our infrastructure, our social systems,” he says. “What we already see is worrisome, but this is going to be an order of magnitude more worrisome.”

And with every year that goes by without shifting the incentives, both the costs and the future fiscal liabilities get larger. Many observers believe that after a major disaster, particularly one of Sandy’s size and scope, there’s a window—maybe six months, maybe a year—for a real shift in direction. Even with Congress frozen in denial, there’s a lot the Obama administration could do: The Veterans Administration could stop underwriting mortgages on homes in flood-prone areas, and the Department of Commerce could deny economic development grants to projects on the coast. The Department of Housing and Urban Development could situate new low-income housing away from flood zones, and the Department of Transportation could build roads where they won’t be under water in the near future.

We’re already spending billions on responding to storms and disasters made worse by climate change, notes Ruth; Sandy gave us a chance to think differently. “Why don’t we take [that money] and invest in infrastructure in ways to overcome the existing inefficiencies and improve quality of life?” he asks. “And then as we do this, reduce the vulnerability. Instead of having this downward spiral, have an upward one.”

In the end, says Stiles, it might be a matter of how many disasters it takes to generate momentum. “I look at these little moments, this incremental progress, but I wonder, ‘Is there enough time? Can we make it?'” he says. “Are there enough of these events coming up, and are we smart enough to catch up with the change that nature is going through?”

This story was supported by a Middlebury College Fellowship in Environmental Journalism.