Flooding in Breezy Point, Queens, during Sandy.Brett Brownell, Mother Jones

One year ago, when Superstorm Sandy devastated much of New Jersey and New York City, the event sparked an intense national discussion about an issue that had gone mysteriously undiscussed during the presidential campaign: climate change. According to research by media scholar Max Boykoff of the University of Colorado, there was actually more media coverage of climate change in leading US newspapers following Sandy than there was following the recent release of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Fifth Assessment Report.

Why? According to NASA researchers, Sandy’s particular track made it a 1-in-700-year storm event. It was, to put it mildly, meteorologically suspicious.

So now, with a year’s distance and a lot of thought and debate, what can we say about climate change and Sandy—and hurricanes in general? A lot, as it turns out. Here’s what we know:

1. Sea level rise is making hurricanes more damaging—and Sandy is just the beginning. The most direct and undeniable way that global warming worsened Sandy is through sea level rise. According to climate researcher Ben Strauss of Climate Central, sea level in New York Harbor is 15 inches higher today than it was in 1880, and of those 15 inches, 8 are due to global warming’s influence (the melting of land-based ice, and the thermal expansion of seawater as it warms). And that matters: For every inch of sea level rise, an estimated 6,000 additional people were impacted by Sandy who wouldn’t have been otherwise. That’s why Strauss told me last year, in the wake of the storm, that there is “100 percent certainty that sea level rise made this worse. Period.”

And what’s true for Sandy is true for every hurricane that makes landfall. While numerous other factors, such as the tidal cycle, also affect the size of a given storm’s surge, global warming is now a measurable part of the total impact. And the more seas rise in the future, the worse the impact gets—and the more likely future Sandys become. “Coastal communities are facing a looming [sea level rise] crisis, one that will manifest itself as increased frequency of Sandy-like inundation disasters in the coming decades along the mid-Atlantic and elsewhere,” as a recent American Meteorological Society report put it. In fact, a recent analysis by Mother Jones, using data from Climate Central and the National Climate Assessment, finds that by the end of the century the chance of Sandy-level flooding in Lower Manhattan in any given year increases to 50 percent.

2. Hurricane rainfall will also be more damaging in the future due to global warming. The principal flooding damage from Sandy came through its storm surge, not its heavy rains. But in other devastating storms, that won’t necessarily be the case. Hurricanes are, at minimum, a triple threat, and can damage lives and property through rainfall, through storm surge, and due to their powerful winds.

We can say with some confidence that global warming is generating more rainfall in storms like Sandy. The reason is simple: Warmer air holds more water vapor, due to basic physics. “For 1 degree Fahrenheit, it’s something like 5 percent more moisture in the atmosphere,” as climate scientist Kevin Trenberth of the National Center for Atmospheric Research has put it.

Extreme precipitation events in the United States are already on the rise, and this trend, like sea level rise, is expected to continue in the future. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, by the end of the 21st century we should expect a roughly 20 percent increase in hurricane rainfall.

3. Hurricanes may also be more intense in the future. A knottier issue involves whether the average hurricane is already more intense (in other words, having higher wind speeds) than it was in the past due to global warming—or whether it will be in the future. This is the question that gets the most press attention, even as it also remains among the hardest to answer.

If you want to go with the conservative (and somewhat dated) scientific view, then the latest IPCC assessment says there is “low confidence” that hurricanes have already gotten more intense due to global warming. The IPCC also says it is “more likely than not” that this will occur by the second half of this century, at least in two major basins that have a lot of hurricanes—the North Atlantic and the Western North Pacific (where they’re called typhoons).

The IPCC, however, has a cutoff date and as a result, cannot always cite the most cutting-edge research. That includes one recent paper suggesting that hurricanes are already more intense, as the global population of storms has shifted toward more Category 4 and 5 storms, and proportionately less Category 1 and Category 2 storms. This issue remains heavily debated within the scientific community, however.

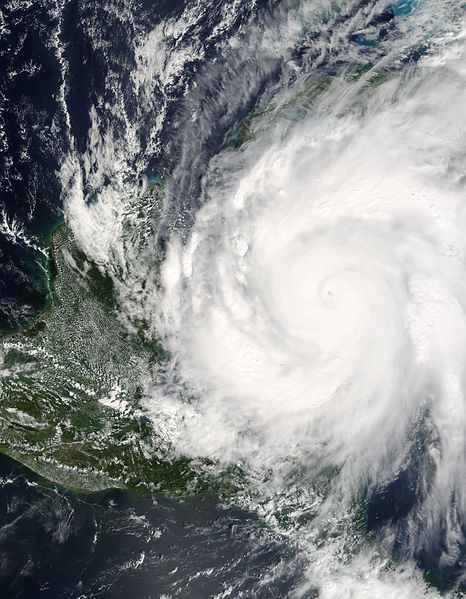

4. Will there be more hurricane left turns into New Jersey? But where things get really scientifically tricky is the matter of storm paths. One of the reasons that Sandy was so devastating is that it, in effect, swung left and slammed into the East Coast. That’s exceedingly rare behavior for an Atlantic hurricane. By the time they reach the mid-latitudes, most of these storms “recurve” to the northeast, a path that often ensures that they miss land.

That pattern was interrupted in the case of Sandy, however, by what is called a “blocking” event: A ridge of high pressure over Greenland that drove the storm westward, leading to this devastating track:

So will such atmospheric blocks become more likely in the future?

Officially, the IPCC says no. Or rather, in scientist speak: “There is medium confidence that the frequency of Northern and Southern Hemisphere blocking will not increase, while trends in blocking intensity and persistence remain uncertain.” However, a number of researchers disagree with this assessment, most notably Jennifer Francis of Rutgers University, who argues that the rapid warming of the Arctic is leading to a more loopy jet stream and, thus, more blocking patterns. This, too, is likely to be a hotly debated issue in the coming years.

So we already know global warming is making hurricanes more dangerous, through sea level rise and rainfall if nothing else. We don’t know everything, yet. But we know more than enough to be worried.