China is in the midst of a love affair with pork. Its consumption of the stuff has nearly doubled since 1993 and just keeps rising. The Chinese currently eat 88 pounds per capita each year—far more than Americans’ relatively measly 60 pounds. To meet the growing demand, China’s hog farms have grown and multiplied, and more than half of the globe’s pigs are now raised there. But even so, its production can’t keep up with the pork craze.

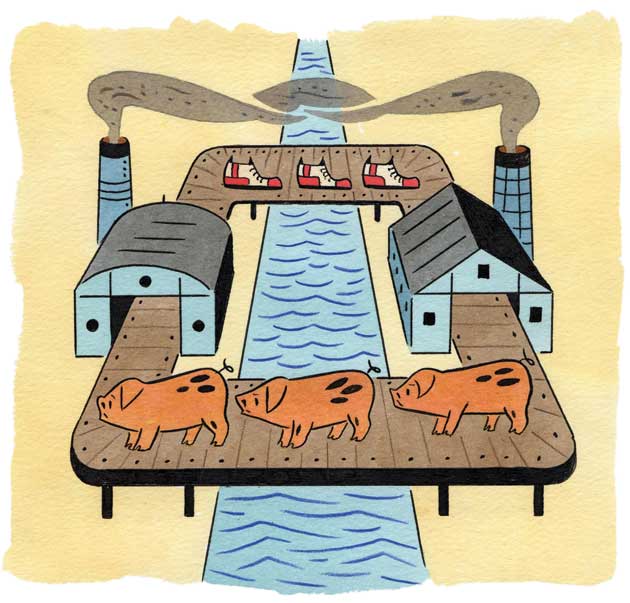

So where is China looking to supply its demand for chops, ribs, loins, butts, and bellies? Not Southeast Asia or Africa—more like Iowa and North Carolina. US pork exports to China surged from about 57,000 metric tons in 2003 to more than 430,000 metric tons in 2012, about a fifth of all such exports. And that was before a Chinese company announced its intention to buy US pork giant Smithfield Foods in 2013. The way things are going, the United States is poised to become China’s very own factory hog farm. Here are a few reasons why:

It’s now cheaper to produce pork in the US than in China. You read that right: Our meat industry churns out hogs for about $0.57 per pound, according to the US Department of Agriculture, versus $0.68 per pound in China’s new, factory-scale hog farms. The main difference is feed costs. US pig producers spend about 25 percent less on feed than their Chinese counterparts, the USDA found, because the “United States has more abundant land, water, and grain resources.”

Americans are not as fond of “the other white meat” as we once were. You wouldn’t know it from the menus in trendy restaurants, but US consumers’ appetite for pork hit a peak in 1999 and has declined ever since. Yet industry, beholden to shareholders demanding growth, keeps churning out more. According to its latest projections, the USDA expects US pork exports to rise by another 0.9 metric tons by 2022—a 33 percent jump from 2012 levels.

Much of China’s arable land is polluted. Fully 40 percent has been degraded by erosion, salinization, or acidification—and nearly 20 percent is tainted by industrial effluent, sewage, excessive farm chemicals, or mining runoff. The pollution makes soil less productive, and dangerous elements like cadmium have turned up in rice crops.

Chinese rivers have been vanishing since the 1990s as demand from farms and factories has helped suck them dry. Of the ones that remain, 75 percent are severely polluted, and more than a third of those are so toxic they can’t be used to irrigate farms, according to a 2008 report by the Chinese government. According to the World Bank, China’s average annual water resources are less than 2,200 cubic meters per capita. The United States, by contrast, boasts almost 9,400 cubic meters of water per person.

Chinese consumers are losing trust in the nation’s food supply—and will pay for alternatives. A spate of food-related scandals over the past half decade has made food safety the Chinese public’s No. 1 concern, a 2013 study from Shanghai Jiao Tong University found. Judith Shapiro, author of the 2012 book China’s Environmental Challenges and director of the Natural Resources and Sustainable Development program at American University, says she expects Smithfield pork to command “quite a premium” in China, because it’s perceived as safer and better than the domestic stuff. Already, “US pork is particularly popular and commands premium prices, as it is viewed as higher quality due to our strict food safety laws,” a Bloomberg Businessweek columnist reported last July.

But what’s good for pork exporters may not be good for the United States: More mass-produced pork also means more pollution to air and water from toxic manure, more dangerous and low-wage work, and more antibiotic-resistant pathogens. And that’s just the beginning. In addition to ramping up foreign meat purchases, China is also rapidly transforming its domestic meat industry along the US industrial model—and importing enormous amounts of feed to do so. The Chinese and their hogs, chickens, and cows gobble up a jaw-dropping 60 percent of the global trade in soybeans, and the government may soon also ramp up corn imports—because while Beijing currently limits foreign corn purchases, meat producers are clamoring for more. And where does a third of the globe’s corn come from? You guessed it: The good old USA.