Inslee photo: Joe Mabel/Wikimedia Commons

When Jay Inslee was elected governor of the state of Washington in November of 2012, climate campaigners rejoiced. As a congressman, Inslee had a top-tier environmental record, and not just that: He knew climate and clean energy issues inside-out. The co-author of the 2007 book entitled Apollo’s Fire: Igniting America’s Clean Energy Economy, he also worked closely on the 2009 passage of cap-and-trade legislation in the US House of Representatives and was a co-founder of the House’s Sustainable Energy Caucus. No wonder that upon his election in Washington, the League of Conservation Voters declared that Inslee was poised to become “the greenest governor in the country.“

Sure enough, Inslee’s term got off to a great start: Last October, he joined the governors of Oregon and California and the Premier of British Columbia in endorsing the Pacific Coast Action Plan on Climate and Energy which pledges that those states (or, in BC’s case, that province) will set a consistent price or cap on carbon dioxide emissions (something California and British Columbia have already done), adopt low-carbon fuel standards, and more.

But there’s just one problem: Shortly after Inslee’s election, two Democrats elected to caucus with the Republican minority in the Washington state senate, thus thwarting what otherwise would have been a Democratic majority in both houses. Instead of holding a 26-23 majority in the Senate, Democrats instead became a de facto 25-24 minority. And that razor-thin edge in the Washington state Senate is currently blocking Inslee from achieving many of his objectives.

The partisan tension became apparent with Washington state’s Climate Legislative and Executive Workgroup, or CLEW, a bipartisan panel composed of two Republican and two Democratic legislators, along with Inslee as a non-voting member. Their task was to recommend a set of policies that would let Washington state adhere to greenhouse gas emissions goals that had been enacted in 2008: a reduction to 1990 emissions levels by 2020, then 25 percent below those levels by 2035, and finally, fifty percent below by 2050.

The workgroup convened sessions and public deliberations around the state—but reached no bipartisan consensus. “We had over 900 citizens come out speaking overwhelmingly in favor of climate action, and close to 10,000 comments,” says Becky Kelley, deputy director of the Washington Environmental Council. “So, evidence that people really are calling for action.” Yet the Democrats and Republicans on the working group could not find common ground. They issued two separate reports, with the Democrats and Inslee endorsing strong climate action and the Republicans suggesting a variety of options, but not a central policy to cap greenhouse gas emissions, citing a “currently insufficient analysis of costs.”

There has been more friction on the issue of a proposed low carbon fuel standard. In a January 2014 letter, Inslee charged Republican State Senator Curtis King, who co-chairs the Transportation Committee, with having misrepresented the governor’s policy goals by incorrectly labeling the standard a “tax.” In fact, the idea is to require a gradual reduction in the carbon content of fuels through a variety of means, ranging from blending in biofuels to encouraging more electric vehicles. “There is no element of a clean fuels standard that could in any way be called a ‘tax,'” wrote Inslee, later adding that a standard “would include cost containment measures to ensure that fuel prices are not significantly affected.” King responded by asking Inslee to “categorically deny” any intention to impose a fuel standard by executive action, in effect bypassing the legislature. King later charged that Inslee “refuses” to take this option off the table.

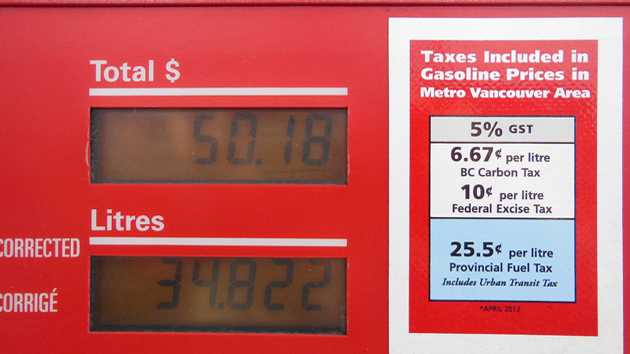

And even as Inslee faces Republican resistance at home, his climate action partners may be growing a little impatient. British Columbians, for instance, have already put a price on carbon through a carbon tax, and are waiting for their southern ally to catch up to them. In the meantime, there are frequent charges that drivers who go across the border into Washington to gas up are partially undermining the tax’s effectiveness, and at least some evidence that this is happening, at least to a modest extent.

All of which underscores that if Washington acts strongly on climate, the impact will extend far beyond Washington. For the state will be strengthening and reinforcing what California and British Columbia have already done, and the more these Pacific coast states are unified, the more the United States and even the world will have to take notice. “The sense is that if the west coast as a bloc acts, if we’ve got real climate policy from BC to Baja, that’s the world’s fifth largest economy,” says Kelly of the Washington Environmental Council.

In the meantime, though, Inslee’s position within his state is much like that of President Barack Obama nationally, observes David Roberts of Grist magazine. “He wants to act, but he’s got no Republicans in the legislature on his side,” says Roberts, “so if he gets anything done, it’s going to be through executive powers.”

So what happens next? Eric de Place, policy director of the Sightline Institute, a Seattle-based environmental think tank, thinks that if gridlock persists beyond 2014, there’s a chance that a citizen-led ballot initiative in Washington state could allow the public to vote directly on how to curb carbon emissions. Before, that, though, he thinks that Inslee may ultimately try to opt for a policy, like a carbon tax, that might be made palatable to state Republicans: The tax could be designed so that the revenue that it brings in would go towards other state budget shortfalls, such as in the transportation sector and in education.

In his inaugural address as governor, Inslee declared that on leading the nation in green policy, “It is clear to me that we are the right state, at the right time, with the right people.” But now, that delicate balance may have shifted. “I’m certain the governor feels that not enough is getting done on climate action,” says Eric de Place of the Sightline Institute. The question is what Inslee plans to do about it.