It’s 6 a.m. and my head is splitting from the roar of David Bronner’s Vitamix blender pulverizing frozen berries and hemp milk. The 40-year-old CEO of Dr. Bronner’s Magic Soaps—who looks like a raver version of Captain Jack Sparrow—kept me up past midnight drinking beers, smoking spliffs, and listening to Deltron 3030 and Gorillaz as he regaled me with stories about LSD trips in Burning Man’s Sanctuary tent and his early days as a squatter and club kid in Amsterdam. Shivering out from under the Mexican blanket in his guest bedroom, I dimly recall the two of us dancing in his backyard and expounding upon the hugeness of the universe. “You’ve got to come to our board meeting tomorrow morning,” Bronner told me at some point between the vegan tapas and my fifth Amstel Light.

But the Advil still hasn’t kicked in as we load his extra longboard (“the Shredder”) into his pickup and roll down the hill to Carlsbad’s Terramar Beach, where we meet a crew of Bronner employees and Bronner brahs—including Mike Hynson, the son of the pro surfer featured in the 1966 cult classic The Endless Summer. Out past the breakers, Bronner starts egging me on as a huge wave approaches: “Go Josh! Go!” I flail desperately, wheezing my way into position atop a glassy wall cresting with foam.

It’s been just 21 hours since I showed up at the hive of cheap warehouses that serves as Dr. Bronner’s global HQ and found the CEO at his flimsy Ikea-style desk, ignoring business calls. An amulet dangled on a hemp necklace over his tie-dyed shirt as he leaned in toward his computer screen, staring at what really mattered to him: the latest internal poll for Washington Initiative 522, a ballot measure to require the labeling of foods containing genetically modified organisms that was coming up for a vote the following month. The initiative, which voters ultimately rejected, was among the costliest in state history: Its backers raised $8 million while its foes in biotech and Big Food poured nearly three times as much into its defeat. Dr. Bronner’s alone donated $2.2 million to the Yes on 522 campaign—after sinking $620,000 into a similar California ballot measure in 2012. “If we don’t win the right to label and enable people to choose non-GMO,” Bronner told me, “then everything is going to be GMO.”

The GMO battle is just the latest in a line of feisty political campaigns waged by the lovably weird cleaning products dynasty, best known for its tingly peppermint liquid soap with the earnestly logorrheic label. (“Absolute cleanliness is Godliness! Teach the Moral ABC that unites all mankind free, instantly 6 billion strong we’re All-One.”) Since its founding in 1948 by Bronner’s grandfather, the Southern California company has become a soapbox for a variety of causes—from its founder’s religious universalism to its recent campaigns to legalize hemp and marijuana, clean up fair trade and organic standards, and combat income inequality. Activism and charitable donations consume about half of the company’s healthy profits. “If we are not maxed out and pushing our organization to the limit, then what are we doing?” Bronner asks.

Embracing lefty lifestyle politics might not seem like the best way to grow a business—until you sit on the orange velour couch in Bronner’s Tibetan-flag-draped office in Escondido and watch the phone light up with calls from buyout firms. In the 15 years since he took over, annual sales have grown 1,300 percent, from $5 million to $64 million. Along the way, the company’s castile soaps have gone from hippie niche products to staples on the aisles at Target. And yet Bronner says he has twice refused offers from Walmart to carry his soaps, even at the undiscounted wholesale price, because he can’t stomach the chain’s politics and crummy worker pay. The best way to go mainstream, he has found, is to be as unapologetically countercultural as possible.

At a time when companies strive to concoct “brand stories” of authenticity and altruism, Dr. Bronner’s succeeds by being itself. “Their activism as a company is not engineered; it wasn’t coached by a public relations firm,” says Joel Solomon, the president of Renewal Partners, a venture capital firm that invests in socially responsible businesses. “Dr. Bronner’s does their thing the way they think it should be done, and nobody is going to change them.”

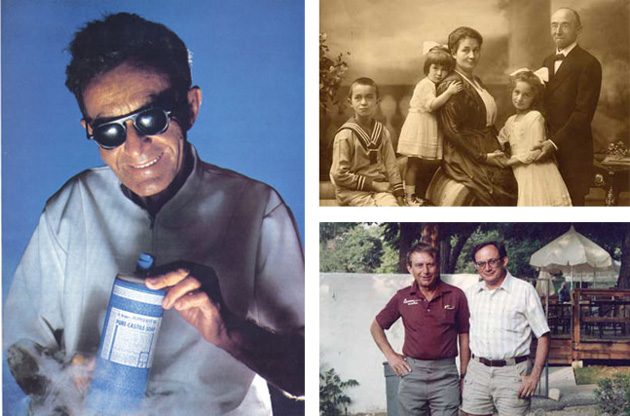

The company shares a niche with progressive rabble-rousers like Working Assets (annual sales: $100 million) and Patagonia ($540 million), but no other brand can match its idiosyncratic story. Emanuel Heilbronner was born into a German Jewish family of soap factory owners in 1908 and immigrated to the United States in 1929. His parents died in Nazi concentration camps, and he dropped “Heil” from his last name because of its associations with Hitler. More interested in godliness than cleanliness, Bronner—who wasn’t really a doctor—invented a Judeo-Unitarian pop religious philosophy, publicizing its tenets on the labels of the soap bottles that he gave away at his lectures. He became so obsessed with spreading his All-One faith that he and his sickly wife put their three children in foster homes for long stretches so he’d have more time to travel and speak. In 1945, he was arrested after a particularly fervent speech at the University of Chicago and committed to a mental hospital for two months. He escaped and fled to Los Angeles, where he founded Dr. Bronner’s All-One God Faith, which now does business as Dr. Bronner’s Magic Soaps.

“The soap was there to sell his message,” David Bronner tells me, “and if you didn’t want to hear it, he didn’t want to sell to you.” Emanuel Bronner’s cosmic ideals and his soap’s 18 suggested uses (contraceptive douche!) found a following among hikers and commune dwellers, even though he was hardly a flower child; he hated communists and never smoked pot. His son Jim rejected his father’s mystical ramblings and went to work for a chemical company, where he developed a firefighting foam for Monsanto that still doubles as fake snow on movie sets. But in 1988, he stepped in to rescue Dr. Bronner’s Magic Soaps after it lost its nonprofit status and declared bankruptcy, recapitalizing it as a for-profit company.

David Bronner, Jim’s son, wasn’t sure he wanted to become the next standard-bearer for a soap-making dynasty. After graduating from Harvard in 1995 with a biology degree, he immersed himself in Amsterdam’s drug culture. “I just had my life explode on many levels of identity,” he recalls of a late-night ecstasy and acid trip at a gay trance club. These experiences, as well as the writings of authors such as Noam Chomsky and Paul Hawken, eventually opened his eyes to the value of his grandfather’s All-One philosophy and the power of the soap company as a vehicle for change. In 1997, he let his dad know that he was ready to work for the family business, but only “on activist terms.”

A year later, Jim Bronner died of lung cancer and David, just 25, took over as CEO. He decided early on that he’d rather feel good about his job than worry about making a ton of money. In 1999, he capped the company’s top salary at five times that of the lowest-paid warehouse worker—Bronner now makes about $200,000 a year. He has hired a lot of people he met at Burning Man, including Tim Clark (official title: Foam Maestro), a muscular guy whose job mostly consists of driving a psychedelic, soapsuds-spewing fire truck to music festivals. That’s about as close as the company gets to actual marketing. “We’re basically like a nonprofit,” Bronner explained as we grabbed coffee in the office of his mom, Trudy, the firm’s chief financial officer. “But we aren’t,” countered Trudy, who could easily pass for a church lady with her silver cross centered on a prim maroon turtleneck sweater. “We’re a for-profit business. And we make good money and pay our employees really well.”

Still, the minuscule ad budget and cap on executive pay leave the company with plenty of cash to improve its products and fund social campaigns—goals that, as luck or savvy would have it, often go hand in hand. At one point, for example, Bronner decided to add a new ingredient, hemp oil, which gave the soap a smoother lather. But there was a hitch: Not long after he acquired a huge stockpile of Canadian hemp oil, the Bush administration outlawed most hemp products. “Technically, we were sitting on tens of thousands of pounds of Schedule I narcotics,” he recalls.

Rather than destroy his inventory, Bronner sued the Drug Enforcement Administration to change its stance on hemp, a nonpsychoactive strain of cannabis. Hemp oil contains so little THC that you’d have to consume a bathtub full of the stuff to get high. To press the point, Adam Eidinger, who has since become the company’s “director of social activism,” set up in front of DEA headquarters and served agents free bagels with poppy seeds (which in theory could be used to make heroin) and orange juice (which naturally contains trace amounts of alcohol). In 2004, a federal court sided with the company and struck down the ban.

Three years later Dr. Bronner’s, by then the world’s first certified-organic soap company, sued rivals such as Kiss My Face and Avalon Organics for falsely advertising their products as organic. (The suit, rendered largely moot after Whole Foods began policing the organic claims of its personal-care suppliers, was ultimately dismissed.) When Bronner couldn’t find certified-organic and fair-trade sources for palm, coconut, and olive oil, he grew his own in Ghana and Sri Lanka, and scaled up existing projects in Israel and the West Bank. Coconut oil now accounts for 12 percent of Dr. Bronner’s sales, almost as much as bar soap.

In recent years, Bronner has been arrested twice for his activism. In 2009, he planted hemp seeds on the lawn of DEA headquarters in Washington, DC, to protest a ban on domestic cultivation. He was busted again in 2012 for milling hemp oil in front of the White House—he’d set up shop in a cage, and police had to saw through the bars to take him into custody. Next he hopes to partner with renegade farmers to manufacture America’s first line of domestically grown hemp-based foods. “The activism side of the company enables us to take risks that no sane company would,” Bronner says. “The point of what we are doing is to fight, and the products serve that.”

Nowhere has that attitude been more evident than in the Washington GMO battle. While many organics companies contributed money to the campaign, Dr. Bronner’s temporarily turned its soap label into a Yes on 522 ad, and ran it in magazines (including Mother Jones). “Taking sides on a political campaign like that is totally unprecedented in the world of product labeling,” Robert Parker, the president of the company that prints Dr. Bronner’s labels, told me as we bobbed in the waves off Terramar Beach.

On the day I met Bronner, his activism director Eidinger was arrested for a Yes Men-style stunt lampooning the biotech industry’s clout in Washington, DC. Posing as a Monsanto lobbyist, he entered a Senate office building and dumped $2,000 in singles—”enough to look like money raining down,” he later explained—from a balcony. Eidinger is also the brains behind the anti-GMO group Occupy Monsanto and a fleet of cute “Fishy Food” art cars (Fishy Sugar Beet, Fishy Tomato, etc.) that Dr. Bronner’s commissioned to drive cross-country and make light of how transgenic crops sometimes incorporate fish genes. “I have no in-principle objection to genetic engineering or synthetic biology,” Bronner insists, citing his biology background and his dad’s work for Monsanto. His real problem with GMOs has less to do with Frankenfood fears than with the documented effects of herbicide- and pest-resistant GM crops, which were sold as a way to reduce harmful spraying. Studies have found that they’ve instead given rise to new superbugs and superweeds that demand ever-stronger pesticides and herbicides. “Far from freeing us from the chemical treadmill,” Bronner says, “GMOs are doubling down on it.”

His loss to the biotech industry in Washington state hasn’t dampened Bronner’s lust for battle. “If this was 2016″—a presidential election year—”we would have destroyed them,” he says, blaming low turnout for the measure’s defeat. “And that’s what we are going to do.” (A second try in California could be next, Eidinger says.)

Before we headed to his house, Bronner took me to see the company’s future headquarters—a bright, 120,000-square-foot warehouse a few hundred yards down the road from a Home Depot. There, Bertine Kabellis, his spunky, Haitian-born factory manager, details what they’re doing to turn the bland corporate space into something more homey. The factory store will include a “fragrance bar,” a soap-bottle refill station, and a hemp activism diorama featuring a Bronner look-alike mannequin sorting through cannabis plants in a cage. The store, Kabellis enthuses, will also carry Dr. Bronner-branded pinhole glasses—which create strange visual effects.

“Leopard-print Speedos?” Bronner asks, out of the blue. “Which I have to get for Palm Springs Pride. I’m gonna rock ’em.”

As Kabellis explains the layout of the organic farm-to-table employee cafeteria, Bronner interrupts. He wants to show us a photo he’s just received on his phone: It’s Eidinger in his business suit, making snow angels in a big pile of dollar bills.

“That’s so ridic-u-lous!” Bronner intones, beaming as he slips the phone back into his baggy hemp trousers. “It’s so rad!”