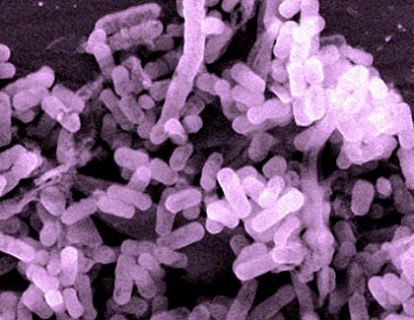

PathDoc/Shutterstock

In 2011, Mark Smith was working on a Ph.D. in microbiology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology when his friend’s cousin—we’ll call him Steve—was diagnosed with C. difficile. Known by the shorthand C. diff, it is now the most common hospital-acquired bacterial infection, and, as the name implies, it’s difficult to treat. Patients have near-constant severe diarrhea and bleeding from the bowels that can last for months, or even years. Many sufferers can’t hold a job because they’re housebound.

Like many C. diff patients, Steve wasn’t getting much relief from antibiotics. There are currently between 500,000 and 3 million cases of C. diff. Of those, a small but significant portion—perhaps as many as 120,000—continue to have symptoms after three rounds of standard treatment. But Steve knew of something that might work. He’d researched fecal transplants, a bizarre-sounding therapy in which patients receive an enema of someone else’s feces, in the hopes that the healthy sample will reintroduce the bacteria lost in the sick patient.

It sounds disgusting, but given the alternative—colon removal—fecal transplants can be a godsend for C. diff patients who don’t respond to the standard battery of antibiotics. The raw material is abundant and the procedure is easy. Doctors, health officials, researchers, and entrepreneurs have begun to see the potential of fecal transplants to treat not just C. diff, but perhaps a multitude of ailments, from irritable bowel syndrome to chronic constipation.

Steve asked Smith about the procedure, and Smith read the literature. As a treatment option, a fecal transplant looked great, but at the time, Steve couldn’t find any doctor willing to help. The stool donor would need to be screened for other infectious diseases, and physicians were reluctant to order diagnostic tests for someone who wasn’t sick. If the tests found something, the doctor would be responsible for treating the donor as a patient.

“I felt like I was part of a system that was failing,” Smith told me in an email. “We had a serious public health problem and we already knew the solution to it. Yet somehow the solution wasn’t getting out to patients.”

After suffering for a year and a half, Steve persuaded his roommate to donate some stool. Without a doctor in sight, he used an enema to perform the transplant himself in his apartment. He started to feel better almost immediately.

Steve isn’t the only patient to have attempted a DIY fecal transplant. On YouTube videos and on a site called The Power of Poop, patients share guides and tips for doing transplants in their homes.

In one scrappy video that’s been viewed 38,000 times, a mother who goes by “HomeFMT” (for “fecal microbiota transplant,” the technical term for the procedure) stands at a bathroom sink listing what you’ll need—a strainer, a plastic spoon, a blender—then demonstrates how to force the poop through a sieve before putting it in an enema for her daughter.

The girl was sick, the mom explains—she doesn’t say with what—and she tried everything. But after one dose of mommy’s poop, the symptoms were gone within 24 hours. She clutches the full enema as if it were a family heirloom. “Fecal transplant has truly been our miracle,” she says, “and hopefully it will be yours.”

But adding a foreign agent into your body can be dangerous. Along with the “good” bacteria in fecal matter, there can be pathogens, as well. Clinics can test samples for disease so that patients don’t end up even more sick than before, but that requires a lab and a trained staff.

Tracy Mac, the founder of The Power of Poop site, told me by email that “ninety-nine percent of people I have encountered want to use a doctor for peace of mind and are forced to DIY,” because they can’t get treatment in hospitals.

After Steve’s ordeal, Smith began talking to a friend, James Burgess, who was then working for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The pair considered starting a company to provide feces to doctors, but quickly backed off the idea. The bacterial makeup of a person’s stool changes over time, making it hard to provide a consistent product. What’s more, the efficacy of fecal transplants is somewhat of a mystery. There’s a vast diversity of bacteria in the colon—more than the rest of the human body—yet no one knows which bacteria make a healthy person’s poop restore the bacteria in a sick person’s colon, or even whether the key component is dead or alive.

“It didn’t really feel like a high-value business to us,” Burgess explains. “But it felt important from a public health perspective.” So in 2012, they formed OpenBiome, a nonprofit stool bank at MIT that collects, screens, and sells frozen, transplant-ready fecal matter to hospitals at cost (about $250 per dose). With more than 70 hospitals around the United States using their stool to treat patients, it’s currently the largest of a family of nonprofit stool banks, having shipped more than 840 treatments to 87 hospitals in 30 states and the District of Columbia.

But whether OpenBiome will be allowed to continue its work now depends on the Food and Drug Administration. The agency has recently taken the first steps to regulate fecal matter—and the medical community is divided over the right approach. Some doctors and researchers, like OpenBiome’s founders, believe it should be considered a tissue, like blood or organs. Others have suggested the FDA should treat it as a biologic drug, like a vaccine.

As a tissue, poop could be traded through banks, just like blood or sperm is now, with tests in place to make sure the samples are disease-free. This approach would make raw, the stuff readily available for patients who needed it. Regulating poop as a drug would subject it to a higher standard of safety tests by submitting it to clinical trials and generate data which could benefit the entire field. But critics of that approach (like Smith) say it will limit the supply of this therapy to companies that can afford to undergo the trials.

In May 2013, the FDA cohosted a meeting with the National Institutes of Health, bringing the fledgling field’s top doctors and researchers together to discuss the latest research and treatment options. At the meeting, the agency announced that poop would be regulated under a regime for new drugs whose effects, intended and otherwise, were not yet understood.

Though presented as a draft regulation, the declaration had some immediate effects: Any doctor using the technique to treat a patient would have to file a ream of paperwork and their results with the government.

On the second day of the meeting, Lee Jones, an entrepreneur with decades of experience at the fore of medical technology companies, took the stage. Where Smith and Burgess had seen an entrepreneurial dead end, she and a few others saw an opportunity. In 2011, she cofounded Rebiotix, a Minnesota-based startup with the aim of making fecal transplants “widely available through a commercialized prescription product.”

That product, called RBX2660, was a prepackaged enema of poop, containing stabilizers and other proprietary compounds, then in the first stage of the FDA’s three-stage process for approving new drugs. (As of this writing, it’s still undergoing clinical trials.) Everything was in one unit; doctors wouldn’t have to handle raw stool, or thaw it like they would if it came frozen in a jar. Pending FDA approval, the enemas could be shipped to hospitals as prescribed.

Jones presented the new product as a time-saver for doctors. “You have to find the donor, you have to process the material,” she said at the meeting. “Once we deliver a product, all that stuff goes away for the physician, but it’s not going to be free.” (Jones says Rebiotix has not determined a price for its product yet.)

At the meeting, doctors showed signs of interest, but they had some questions: Rebiotix sourced its material from just five donors. What would happen if one died? Also, as OpenBiome’s founders had wondered, how could you market a standardized medical product whose raw material is prone to so much variation? Jones countered that the therapy available now is crude, but it will only get better as researchers learn more and can isolate exactly those bacteria that made feces work as a therapy. While Rebiotix can’t replicate the bacterial contents of stool with exacting precision, Jones told me, the company tests it for the presence of bacteria that are known to be lacking in C. diff patients. If Rebiotix gets through the approval process, RBX2660 will be ready to ship around the country next year.

A few weeks after the meeting at NIH, the FDA changed its approach. Fecal transplants would still be regulated as a drug, but to keep them moving (at least until a treatment was finally approved), the agency said it would exercise “enforcement discretion”—meaning health care providers could go on administering transplants for recurrent C. diff patients without filing paperwork for new drugs.

In February 2014, the FDA issued a second draft of its guidelines. The Infectious Diseases Society of America, a 10,000-member organization of doctors and scientists, offered a blanket endorsement of the FDA’s position. (Johan S. Bakken, a leading researcher in the field, is the vice president of the IDSA’s board, and serves on the physician advisory board of Rebiotix but has no financial relationship with the company—nor does he plan on having one in the future.)

Meanwhile, OpenBiome joined the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, a major professional society, to speak out against the agency’s choice to regulate poop as a drug because, they said, it would limit access fecal transplants.

“In the long term,” OpenBiome wrote in its comments, “we feel that FMT is poorly suited to the paradigm of a biologic [drug], because the active ingredients remain unknown, the material is highly variable and it is fundamentally impractical or even impossible to fully characterize.”

The FDA has yet to issue its final rule on the matter—and the future of OpenBiome and Rebiotix hang in the balance. Right now, the FDA’s “enforcement discretion” provision gives OpenBiome a sliver of space to exist while the government promises to look the other way. If the gap is closed, though, Smith says that OpenBiome’s distribution will be severely limited, to the point that the organization will effectively becoming a research operation.

“If that happens, we’ll have served our purpose,” Smith says with an air of resignation. He still wonders aloud about the financial cost of commercializing fecal transplants. “But first and foremost patients will be getting treated,” he says, “and that’s good.”