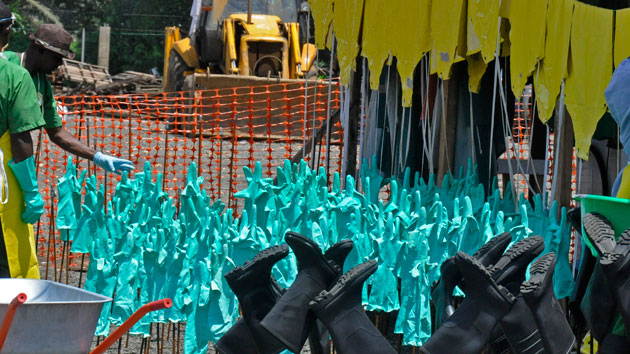

A worker hauls rice donated by the US government to a distribution center in Monrovia.Morgana Wingard-UNDP/USAID

The news out of Liberia has been upbeat lately, with fewer and fewer cases of the deadly Ebola virus being reported. But even as the direct threat posed by the disease appears to be receding, experts are warning that it has given rise to a related crisis: rampant hunger.

To assess the problem, researchers from Mercy Corps, an NGO based in Portland, Ore., spoke with 122 households and 122 vendors in three of the most heavily afflicted parts of the country—Lofa County, once the epicenter of the Liberia’s Ebola outbreak; Monrovia, the capital; and Nimba County. Their report, published last week, depicts a population gradually moving from one disaster to another. The most striking findings: 90 percent of respondents said they were eating less at every meal since the beginning of the outbreak, and 85 percent were eating fewer meals every day.

The report shows that even though the number of people of infected with Ebola has been relatively small—never more than a fraction of all residents in even the hardest-hit regions—the resulting epidemic of hunger has become far more widespread.

There are two reasons for this problem. One is the increasing scarcity—and rising cost—of food imports. Vendors in Lofa (which borders Sierra Leone and Guinea) and Nimba (which borders Guinea and Ivory Coast) typically sourced their goods from neighboring countries since it was cheaper than buying imports that are shipped to Monrovia. But as panic spread and the borders closed, they were forced to acquire their goods from Monrovia, and the country became increasingly dependent on overseas imports. But because of the outbreak, fewer shipping lines have been willing to travel to Liberia. Those that continue to deliver goods have had to purchase additional insurance—an added cost that is further driving up the price of imports.

The food shortage that resulted from the decline in trade has been made even worse by a simultaneous decline in local agriculture. In northern parts of the country—like Lofa—where farmers normally rely on imported seeds from neighboring countries, rice production has fallen by as much as 25 percent in some areas. In the south, which depends heavily on mobile groups of farm laborers, production has fallen by as much as 50 percent as workers have stayed away in an attempt to avoid the disease.

Declining agriculture and trade, combined with a general slowdown in business throughout the country, has led to a collapse of the Liberian economy and a fall in household income. According to Mercy Corps, 66 percent of surveyed households reported that their income has decreased since the outbreak reached epidemic levels. To make up for their losses, people are borrowing money, often to pay for food or other household expenses.

And the hunger problem could get even worse. “If attention is not paid to the economic impact of the crisis the situation will continue to deteriorate over the coming months, with some households reaching critical levels by April/May 2015,” the researchers write.

Back in September—when the epidemic in Liberia was at its peak—we published a series of interviews that journalist and researcher Abel Welwean conducted with people in his neighborhood outside Monrovia. For some residents there, the Ebola crisis, and the looming hunger crisis, invoked memories of the country’s civil war, which ended in 2003. This is how Lawrence, the Monrovia director of an international NGO, put it:

Hunger is really hitting the country… If the ships are not coming, [farmers] are not making rice, the stockpiles are depleted…the animals are eating the crops, what happens then? The production will decrease, the price will increase, and if you don’t have money, what is going to happen? Hunger is going to strike… This is a serious war, without bullets.

Frances, a student who’s university had closed because of the disease, was equally blunt:

Liberia is declining, the economy is declining, and things are just getting difficult on a daily basis. We are not free to move around, we are not free in our own country because of this deadly Ebola virus. We are urging the international community to come to our rescue, for the downtrodden, because pretty soon there will be another war, and that will be the hunger war.