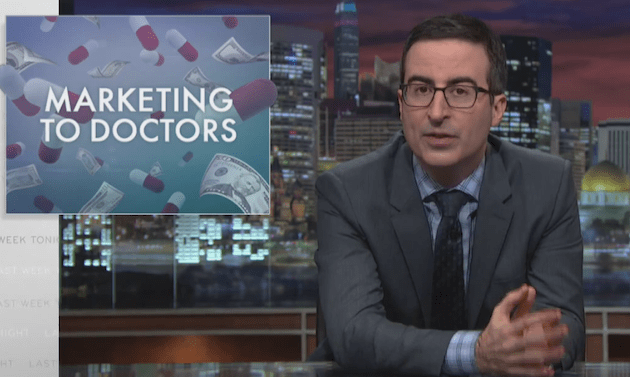

You may have recently seen a TV ad about the “most common eating disorder in US adults”: binge eating disorder. The spot features champion tennis player Monica Seles talking about her struggles with BED, which was classified by the American Psychiatric Association as a medical condition in 2013. “My binge eating episodes would usually happen in the evenings,” Seles explains from a brightly lit kitchen. “I would be back home, by myself, after a long day at the tennis courts and would just eat large quantities of food.”

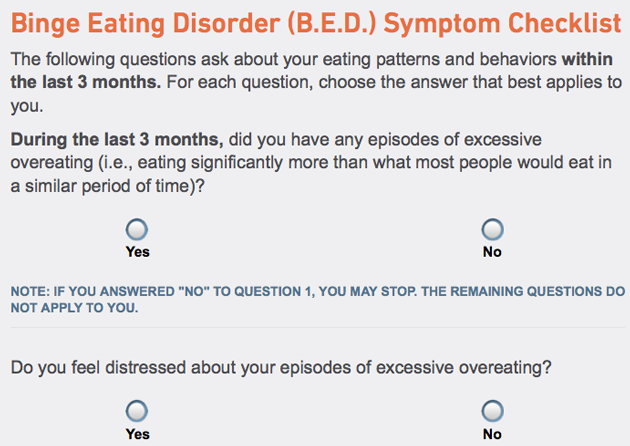

Seles encourages viewers to check out BingeEatingDisorder.com for more information; according to the website, core symptoms include “regularly eating far more food than most people would in a similar time period,” bingeing “on at least a weekly basis for three months,” and “feeling very upset by eating binges.” The website urges potential sufferers of BED to see a doctor, “bring up BED early in the appointment” because time may be limited, and prepare the doctor by sending a Binge Eating Disorder Education Kit.

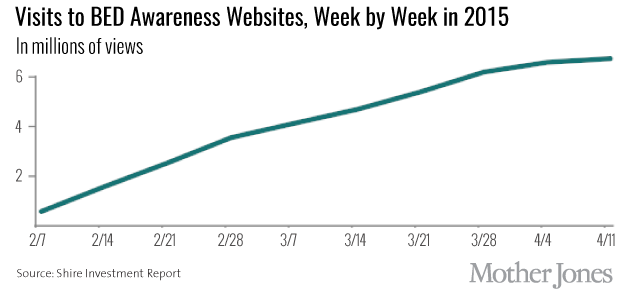

If these seem a little pointed for a friendly PSA, there’s good reason: Both the website and the ad campaign are paid for by Shire, a pharmaceutical company that, in January, won approval from the Food and Drug Administration to market a drug called Vyvanse to treat BED. Vyvanse is a Schedule II federally controlled substance—meaning it’s acceptable for medical use but has high potential for abuse—and it’s the only drug that the FDA has approved for BED. Last year, Shire spent more than $2.5 million on raising awareness among doctors about BED; by 2020, the company expects Vyvanse prescribed for BED to bring in $200-300 million per year.

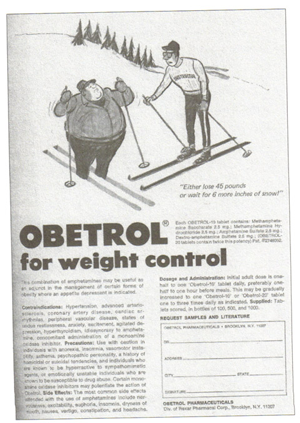

While binge eating disorder is a new diagnosis, Vyvanse isn’t exactly a new drug. An amphetamine, it was until this year marketed exclusively to treat ADHD. But its latest incarnation actually represents something of a return to its roots: Before they became ADHD drugs, amphetamines, of course, were diet drugs.

Doctors began prescribing “rainbow pills,” amphetamines named for their bright colors, in the 1940s and ’50s to help people lose weight. Andy Warhol’s drug of choice was Obetrol, a popular diet pill composed of amphetamine salts, including methamphetamine. By the late ’60s, at the peak of the drugs’ use, an estimated 1 in 10 American women were consuming amphetamines.

After numerous exposes on “Mother’s Little Helper” and “speed freaks” in Ladies Home Journal and elsewhere—as well as a study finding that nearly half of the amphetamine users took the pills for nonmedical reasons—the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (the equivalent of today’s Drug Enforcement Agency) stepped in. Amphetamine products were categorized as federally controlled substances with strict regulation of when and how they could be prescribed. The FDA prohibited doctors from selling the drugs for weight loss; the only approved usages were for narcolepsy and “hyperkinetic disorder of childhood”—today’s ADHD. By the end of the ’70s, production and use of amphetamines had plummeted.

The amphetamines of the ’60s and ’70s were a different breed from the amphetamines of today. Drugs like Vyvanse and Adderall don’t contain methamphetamine, which was responsible for making the pills particularly addictive and rush-inducing. In addition, Vyvanse doesn’t take effect until it’s digested, thus slowing down its onset and making it ineffective to snort.

Yet despite all the changes, many see Vyvanse as a variation on a familiar theme of amphetamines. This is in part because Vyvanse draws its lineage to Obetrol: After pharmaceutical executives saw potential in Obetrol—without the methamphetamine—to treat ADD, it was rebranded as Adderall (short for “ADD for all”). The FDA approved the drug for ADD treatment in 1996; Shire bought the company producing it a year later. Vyvanse, in turn, was developed as a still less abusable version of a key Adderall ingredient and acquired by Shire in 2007.

Binge eating Disorder was first described in 1990 by a psychiatrist named Robert Spitzer. At a meeting to discuss which diagnoses should be included in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the bible of the mental health field that classifies each recognized mental illness and its symptoms, he noted that some patients regularly binged but didn’t fall into the category of bulimia because they didn’t purge. Over the next two years, Spitzer led a landmark study finding the practice of uncontrollable, distress-inducing binges to be a common, untreated problem among individuals participating in weight loss programs—one that some binge eaters likened to an addiction. The evidence led the DSM committee to include BED, defined as binges featuring “impaired control” at least twice a week for at least six months, as a disorder that was “not otherwise specified.” Mental health practitioners were to be aware of its symptoms, but the disorder necessitated more study before it became a full-fledged diagnosis.

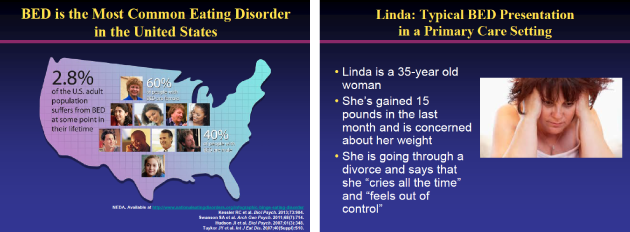

This classification in 1994 served as a rallying call of sorts among eating disorder researchers; between the release of the DSM-IV and the DSM-5, in 2013, more than 1,000 studies were published on the prevalence, epidemiology, and treatments of BED. One frequently cited study by researchers at Columbia found BED prevalent in 2.8 percent of the general population, a rate far higher than anorexia or bulimia. Evelyn Attia, the director of the Columbia Center for Eating Disorders who served on the DSM-5 committee, remembers “very consistent support” from the field that patients were “coming, they were asking for help, and we needed to formally identify them.”

In 2011, Shire researchers began studying the company’s top-selling drug, Vyvanse, as a treatment for BED. The first large trial showed promising results: At the end of about three months, those on high doses of Vyvanse binged about half as much as those on a placebo. By the time of the 2013 release of the DSM-5—which, with universal support from the DSM committee, included binge eating disorder—Shire had already laid the groundwork for its awareness campaign around the condition. Looking through the company’s financial records, one sees a point, in mid-2013, when the bulk of its funding for educational purposes transitioned from teaching doctors how to recognize ADHD, a market that was slowly being eroded by generic drugs, to awareness of BED.

In the year and a half before gaining FDA approval, the company spent about $4 million dollars on medical awareness of BED, including grants to the American Academy of Continuing Medical Education for a program called “the ABC’s of BED” and to the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, to teach doctors about “missed opportunities in the recognition of binge eating disorder.” The company also donated to patient advocacy groups, including a total of $450,000 to the Binge Eating Disorder Association (BEDA) and the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) to fund awareness activities.

In January of this year, Shire’s application to the FDA went through an expedited approval process without the usual consultation from an outside advisory board; an FDA spokesman told me this was because Vyvanse had already been approved for ADHD and there was no existing treatment for BED. The application was based on two studies, both similar in content to the first, and both led by scientists who, between 2013 and 2014, received a combined $67,000 in consulting and travel fees from Shire. A company spokesperson told me that the studies were controlled and double blinded, and that Shire believes the studies were “conducted with the highest of ethical and regulatory standards and integrity.”

The FDA announced its approval of the drug on a Friday in January; by the following Tuesday, the company’s marketing campaign to consumers was up and running, with Monika Seles speaking about her experience on Good Morning America, in People magazine, and in other media outlets.

Two years after BED was added to the official diagnostic vocabulary, mental health experts have mixed reactions to how things are going. “Patients are feeling more confident that they’ll be able to get the appropriate health care for a somewhat recognized diagnosis,” says Attia.

But Shire’s gung-ho marketing has rubbed many practitioners the wrong way. “You can barely turn on the TV without seeing Monica Seles,” groans Marsha Marcus, a University of Pittsburgh psychology professor.

Some see Shire’s BED education campaign as a cynical attempt to repackage a drug that’s been around decades. Using Vyvanse for BED “takes us down the road of the much earlier use of [amphetamines],” says Keith Conners, a professor emeritus in medical psychology at Duke. Indeed, several psychiatrists told me that they consider Obetrol, Adderall, and Vyvanse to be essentially the “same drug.”

A Shire spokesperson told me that the company is clear about the fact that Vyvanse is for BED, not for weight loss, and that Vyvanse labeling and promotional material clearly spell out its risks, including addiction and cardiovascular problems.

Yet even some former Shire employees who staunchly believe in Vyvanse’s efficacy hinted that the awareness campaign wasn’t exactly what they had in mind. “At the time, we assumed this would be focused on psychiatrists who were treating these more severely ill patients,” says Jeff Jonas, who led the initial research. Michael Cola, a former Shire executive who oversaw the development of Vyvanse, was surprised to learn about the Monica Seles ads. “It started out with good intentions,” he said. “I’m not sure where it is today.”