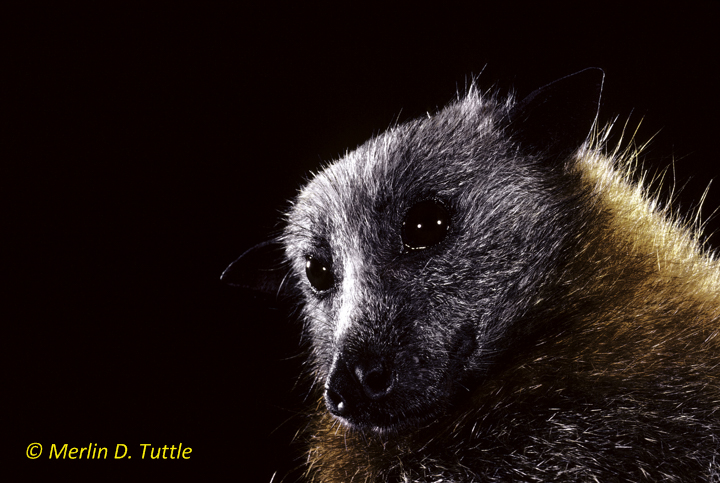

A Wahlberg's epauletted fruit bat with a mouthful of fruit. Merlin Tuttle

Despite the fact that Dr. Merlin Tuttle, 74, has saved millions of bats around the world through his research and advocacy, and has taken hundreds of thousands of pictures of bats (sometimes shampooing them beforehand), he won’t judge you if you are afraid of them.

He won’t even get mad if you’ve tried to hurt one. In his more than 50-year-long career, Tuttle has encountered just about every sort of reaction one could have toward a bat, and witnessed every horrible thing you could do to one. His response? To try to be understanding and then calmly list, as he did with me below, all the ways bats are amazing critters that will, in fact, make your life better.

Since he first discovered bats as a teenager in a cave close to his house in Tennessee, he has devoted his life to them, founding Bat Conservation International, the world’s leading bat advocacy group (which he has since left to found Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation); publishing more than 50 research articles on bats; and lending his work to several National Geographic features. Last week, he a released a charming memoir: The Secret Lives of Bats: My Adventures with the World’s Most Misunderstood Mammals. In it he recounts his incredible adventures saving the stigmatized species from moonshiners in Tennessee caves, poachers in Thailand, politicians in Austin, Texas, and on and on.

He recently talked to Mother Jones about what makes bats so important, how he started photographing them, and why he is optimistic for their future, despite the continuing threats facing the species.

On why people fear bats: “It’s human nature and animal nature that we fear most what we understand least, and bats, because they are active at night, dart around unpredictably, it’s easy to fear them. But the more we learn about them, the easier it is to like them. And most people are just amazed when they find out that there is this incredible variety and that they have highly sophisticated social systems, similar to those of primates and dolphins, and then they find out how valuable they are and probably most importantly learn that the bats just don’t go around attacking people and looking for trouble—even a sick bat is extremely unlikely to ever attack anyone. We all love our dogs and yet dogs are vastly more dangerous in terms of human mortality than bats are. Bats have one of the finest records of living safely with people of any animal in our planet.

“In 55 years of studying bats on every continent where they exist, dealing with hundreds of species, sometimes surrounded by thousands, even millions at a time in caves, I’ve never once been attacked by a bat, I’ve never seen an aggressive bat, and I’ve never contracted any disease from a bat.”

On why bats are valuable to humans: “Bats contribute billions of dollars annually in protecting farmers against crops pests, reducing the need for pesticides that already threaten nearly every aspect of our lives. If you go to a tropical fruit market, you’ll find that some 70 percent of the fruit on sale are pollinated or seed dispersed by bats. The whole tequila liquor industry is based on agave that is highly dependent on bats for pollination. Many of our most valued timber trees are dependent on bats for pollination or seed dispersal. If you go to the East African savannas, the famous baobab tree is highly dependent on bats for pollination. You go to Southeast Asia and the durian is so dependent on bats for pollination that you can’t even grow it in an orchard without bats to pollinate the flowers. And take the banana: All commercial bananas come form wild ancestors that continue to rely heavily on bats for pollination.”

On the change in attitude toward bats since he started studying them decades ago: “When I began devoting my life fulltime to bats back in 1982, just about everybody knew that bats were just ugly, dirty, rabid vermin that were dangerous, and now that is improved rather dramatically. At that time the most frequent call that zoos got about bats was, ‘Oh my god, I saw a bat in my yard last night, I’ve got children, what can I do,’ thinking that the bat was going to attack their children. And yet today those same institutions report that they are much more likely to get a call asking how to put up a bat house and attract bats to the yard. In fact, since the three decades since I introduced the idea of bat houses to North America there are now hundreds of thousands of bats living in people’s bat houses.”

On how he got into bat photography: “Back in 1978, because of my research on bats, National Geographic asked me to write a chapter in their new book Wild Animals of North America on bats. I worked real hard to write a chapter explaining to people that they didn’t have to be afraid of bats, that bats were actually quite valuable to have around. And then I went to Washington, DC, to meet with the editors and see the layout for my chapter in their book. All the pictures were just horrible! They were bats that were caught and tormented into snarling, and then photographed with their teeth bared.

“I was rather shocked to find that after all my efforts to get people over their fear, they were going to put that kind of picture with my story. They agreed that that wasn’t a good thing and sent one of their staff photographers to go to the field for month with me to get some good picture of bats to go with the chapter. But bat photography is difficult, it’s definitely not easy. And in that month he just got three pictures that were really useful for the chapter, and by that time he realized there was as much involved with knowing bats as with knowing photography, and while he was with me I had hardly let him rest for a moment without asking him how and why he was doing what he was doing. So when he left he said look, you know what I know about photographing animals now, I’ve got some spare leftover film, let me leave it with you and why don’t you go out and buy yourself a little bit more equipment and see what you can contribute for the book. And I ended up being the second-most used photographer in the book.”

On the power of photographs to convince people of bats’ value: “I began my photography strictly out of defense of bats. It dawned on me that these pictures were incredibly powerful at changing people’s perception, and so I got excited about photography. Without photography, there would have been no real conservation progress in my opinion.

“It’s so easy to change people’s minds about bats when you are armed with pictures. For kids that love dinosaurs, the dinosaurs all died out, there are bats still alive that are just as fascinatingly strange as any dinosaur, and yet if you like panda bears or something else that’s cute, there are bats that’ll run them stiff competition, too.”

On other methods he used to convince people of bat’s benefit: “I asked a Tennessee farmer one time for permission to go in his cave to study bats, and he said, ‘Oh yeah, you’re very welcome, and just kill all you can while you’re there.’ He just assumed if I was a scientist, I knew bats were bad and I would try to kill them. I came out and I said, ‘You know I really appreciate your letting me go in and look at your bats, I’m interested in learning exactly what all they are eating. You ever seen anything like these beetles?’ And he looks and goes, ‘Oh my god, them suckas eat potato bugs?’ I said, ‘Well a colony the size of yours can probably eat 100 pounds in a night.’

“I came back a month later to do some more research and he on his own decided that each of his bats was worth 5 bucks, and, by George, anyone got near to doing anything bad to his bats was going to have a big problem with him.

“That’s how it works, being able to listen to people no matter how crazy their fears are and trying to stand where they’re coming from, and then instead of getting upset when they tell you they’ve been killing them all their lives, just point out that we’ve all made mistakes in the past and that I’m not worried about what they’ve done in that past, but I assume that now that they understand bats, they’ll probably have a different attitude toward bats in the future.”

On white-nose syndrome, the fungal disease that’s wiped out nearly 6 million bats in North America: “There is no question that the fungus has had terrible consequences, particularly in the Northeast. We definitely need to help them rebuild. We probably never needed conservation action more than we do right now for bats. But the good side of this story is that because of this calamity, millions of people have learned about the value of bats and learned to care about bats who didn’t know anything about them previously. Now, because of the spread of white-nose syndrome, I’m seeing programs starting up all over the country to monitor the status, not just of a few endangered species in a few select locations, but to monitor bats in general and to track them as we do birds, and that’s a very, very important step in the right direction because white nose-syndrome is not the only thing we have to worry about. We can do a whole lot better at protecting bats in the future because of what we’ve learned through white-nose syndrome, and I’m optimistic in that regard.”