President Barack Obama and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau leave the White House Rose Garden on Thursday.Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP

President Barack Obama and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced a new plan to collaborate on climate change Thursday morning. The two leaders pledged to tackle previously unregulated sources of greenhouse gas emissions and promised better conservation of the Arctic.

The plan represents an important evolution in the two countries’ bilateral foreign policy on climate. That policy has become significantly more ambitious since Trudeau took the helm in November from longtime PM Stephen Harper, who was widely seen as an obstacle to climate action and a booster of Canada’s oil industry.

Trudeau, by contrast, has tried to reposition Canada as a leader on climate, not an easy feat for one of the world’s largest oil producers. He campaigned on promises to end fossil fuel subsidies and invest in clean energy. He made a strong showing at the Paris climate talks in December and followed that up with a proposal for a national price on carbon emissions. Although he supported building the Keystone XL pipeline, he seemed to take it in stride when the Obama administration turned the project down. Last week, Trudeau announced a plan to help his country’s provincial governments—which hold a larger relative share of power compared with state governments in the United States—coordinate on clean energy.

Overall, Trudeau’s administration has so far looked like a 180-degree turn from his predecessor, said Erin Flanagan, director of federal policy at the Pembina Institute, a leading Canadian environmental group.

“We look at what’s been accomplished post-Paris and say things are moving forward at a pace we haven’t seen before,” she said. “The proof is in the pudding.”

The most important piece of Thursday’s announcement deals with methane, a potent greenhouse gas that, from a policy perspective, has managed to stay in the shadow of carbon dioxide. CO2 is much more common than methane, accounting for nearly 90 percent of US greenhouse gas emissions, whereas methane makes up about 10 percent. But methane can trap up to 90 times more heat than CO2 in the short term and thus has an outsized impact on climate change.

Methane emissions occur at every stage of the natural-gas production process, from leaky wells and pipelines to smokestacks at power plants. In Thursday’s announcement, both countries committed to reduce these emissions 40 to 45 percent below 2012 levels by 2025. For the United States, that’s just repeating a goal that was already announced in January; a similar target also already existed in Alberta, Canada’s biggest oil-producing province. The key development in today’s announcement is that the countries are promising for the first time to regulate methane emissions from existing sources in the oil and gas sector, rather than simply applying the rules to newly built infrastructure.

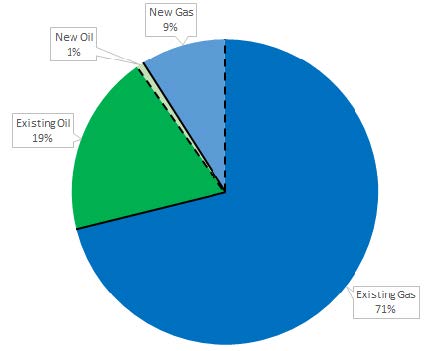

This is important because sources of methane emissions that exist right now (currently operating wells, pipes, storage facilities, etc.) will continue to account for a major share of emissions into the future. Recent studies by the Environmental Defense Fund found that in both the United States and Canada, up to 90 percent of oil- and gas-sector methane emissions in 2020 will come from sources that already exist today. Here’s a chart from the Canada report:

In other words, because it ignored existing sources, Obama’s previous methane policy was pretty toothless. The new rules announced today will have more teeth.

“There’s a dramatic change in policy that is extremely welcome,” said Jonathan Banks, senior climate adviser at the Clean Air Task Force.

That is, of course, if it actually comes to fruition. There’s no guarantee that the regulations will finish winding their way through the byzantine regulatory approval process before Obama leaves office, meaning their ultimate fate could end up in the hands of his successor. Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders have both committed to advancing Obama’s methane agenda; the Republican candidates, of course, have not.