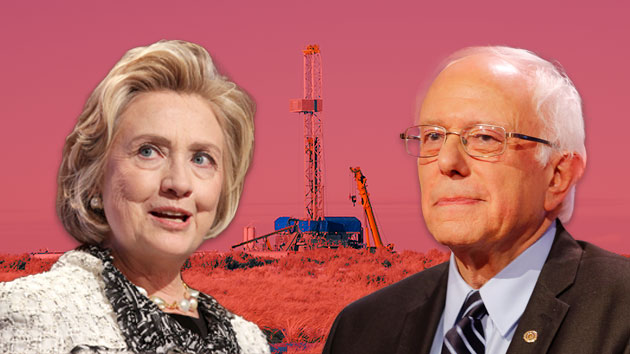

<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-352127300/stock-photo-new-york-city-december-former-secretary-of-state-hillary-rodham-clinton-spoke-at-the.html?src=gDsiqJxWFGDSjuEzw2IW6Q-1-3">a katz</a>/Shutterstock; <a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-388723837/stock-photo-new-york-jan-democratic-presidential-hopeful-senator-bernie-sanders-of-vermont-speaks.html?src=1kAf04Bx82Ik6Y0xXfEm2Q-1-18">Trevor Collens</a>/Shutterstock

California’s Democratic presidential primary on Tuesday is a make-or-break moment for Sen. Bernie Sanders, who needs a big win in the state to take anything resembling momentum to the Democratic convention in July. His rival, Hillary Clinton, has a narrow edge, leading him by about two points in the RealClearPolitics polling average as of Monday morning.

But in addition to its role in the delegate math—after Tuesday, Clinton will likely have secured a majority of the delegates, when unbound superdelegates are factored in—California’s Democratic primary could also be a referendum on how voters in the state want to deal with climate change. California is home to some of the country’s most progressive climate policies, strong industries for both fossil fuels and renewable energy, and high vulnerability to some impacts of climate change, such as droughts like the one that is still ravaging the state (Donald Trump’s opinion to the contrary notwithstanding). According to Yale University polling, 62 percent of Californians are worried about global warming, compared with a national average of 52 percent. A recent poll of California voters in both parties found that clean air and water ranked among the top issues in the presidential election.

In other words, California is uniquely suited to be a prime proving ground for differences between Clinton’s and Sanders’ approaches to issues like fracking and nuclear power.

“I think it’s fair to say overall that California is known nationwide as being an environmental leader,” said Michelle Chan, vice president of programs at Friends of the Earth in California. “And it’s very much part of our identity as Californians: Our environmental values are part and parcel of how we identify politically.”

Both candidates appear to be acutely aware of this. Last week, they courted the environmentalist vote in California. Sanders focused on climate change at a series of rallies, lambasting Trump as a “climate change denier” and calling on Clinton to up her game by coming out in favor of a tax on carbon emissions. Meanwhile, Clinton published an editorial in the San Jose Mercury News that focused on wilderness conservation.

Environmental groups are split between the Democratic candidates. Friends of the Earth endorsed Sanders nearly a year ago, and the Vermont senator also has the support of 350.org founder Bill McKibben. (350.org itself has not yet made an endorsement.) The political arms of the League of Conservation Voters and the Natural Resources Defense Council both support Clinton, as does Gov. Jerry Brown, who has been a forceful advocate for action on climate change. The Sierra Club and Greenpeace remain on the sidelines.

Needless to say, on climate change Clinton and Sanders have much more in common with one another than either does with Trump, who has called it a hoax and vowed to dismantle the global agreement on climate struck in Paris last year. In general, Clinton has stayed fairly close to President Barack Obama’s “all of the above” script on energy resources—that is, continuing some level of fossil fuel production in addition to promoting more climate-friendly sources like wind and solar. Sanders, meanwhile, has advocated a plan that hews closer to environmentalists’ dream scenario, with all fossil fuels left in the ground.

They differ more sharply on fracking. The controversial method of oil and gas extraction, which involves blasting underground shale formations with high-pressure water, sand, and chemicals, is perhaps more relevant to Golden State voters than to residents of any other state. Fracking in California has been in the news a lot recently: The industry has drawn criticism for its high use of water during the drought, and the natural gas industry was blamed for a massive methane leak at a storage facility near Los Angeles in January that drew comparisons to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Just last week, environmentalists were incensed by a new report from the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management that found that offshore fracking in the Pacific is unlikely to have a “significant” impact on the environment.

Sanders’ position is cut-and-dried: a nationwide ban on fracking. Clinton’s position is more nuanced. In a March Democratic debate, she said her administration would place so many new restrictions on natural gas production that “by the time we get through all of my conditions, I do not think there will be many places in America where fracking will continue to take place.” Still, as secretary of state, Clinton helped export American fracking technology to places like China and Eastern Europe. And she has argued—in line with the Obama administration—that although pollution from fracking is insufficiently regulated, it is a preferable alternative to coal and so can be a “bridge” to a less carbon-intensive energy system. There’s plenty of evidence that Clinton could be right, and that a fracking ban could actually backfire by leading the country to depend more on coal. But that might not matter much to California voters, a (slim) majority of whom oppose fracking, according to a 2013 Public Policy Institute of California poll.

In other words, Sanders’ message on fracking has the potential to resonate with California Democrats.

The same could be said of nuclear power, which has also resurfaced in the California news as regulators decide whether to shutter Diablo Canyon, the state’s last nuclear power plant. As with fracking, Clinton sees nuclear power as key to the clean-energy transition, while Sanders wants to shut down nuclear power completely. Neither candidate has weighed in on Diablo Canyon specifically, but in a statement to Mother Jones, a Sanders campaign spokesperson said, “We cannot allow the ailing nuclear industry to endanger the lives of millions of people just to squeeze out every last cent from its failing infrastructure.”

Regardless of which Democrat wins the primary, Trump’s positions on climate change are the polar opposite. So the big question is whether Sanders’ environmentalist supporters in California would be willing to support Clinton if she wins the nomination, rather than risk putting a climate change denier in the White House. Chan, from Friends of the Earth, said that for many environmentalists, Clinton may be an unsavory choice, but she is still one whom many in California could eventually rally behind.

“We have certainly seen Sanders’ entry in the campaign pull her to more progressive positions,” she said. “[It’s] fair to say she’s preferable to Trump.”