A mountain pine beetleJohn Ulan/The Canadian Press/AP

California’s wildfires can be traced back to a tiny bug—or at least that’s what Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) would have you think. So far this year, the state has seen at least 4,500 wildfires burning more than 200,000 acres of forest, resulting in hundreds of evacuations and at least one human death. On Tuesday, the senator tweeted about how an uptick of bark beetles in her state has helped cause the blazes:

(1/3) This great @CAL_FIRE video explains how Calif’s bark beetle epidemic leads to an increased wildfire threat. https://t.co/vwghWeSdqw

— Sen Dianne Feinstein (@SenFeinstein) September 13, 2016

Feinstein asked the US Department of Agriculture to allocate $38 million to fund tree removal projects in hopes of quelling the potential for future fires.

(3/3) Firefighters are reporting unprecedented fire behavior in areas full of dead trees. I’ve asked @USDA to act on tree removal projects.

— Sen Dianne Feinstein (@SenFeinstein) September 13, 2016

As the US Forest Service wrote in a June press release, four years of drought, warmer temperatures, and “a dramatic rise in bark beetle infestation” have weakened the woods and made them dangerously dry. More than 66 million new trees have died in the Southern Sierra Nevada since 2010.

“Bark beetles” describes several species of rice-sized insects that lay their eggs in evergreen trees, choking off the supply of nutrients from the roots of a tree to its limbs. Droughts make trees more susceptible to these insects, and California (along with Colorado, Montana, and other Western States) has seen major increases in bark beetle infestations over the last decade. Nearly 50 million of our country’s 850 million forest acres have experienced beetle outbreaks.

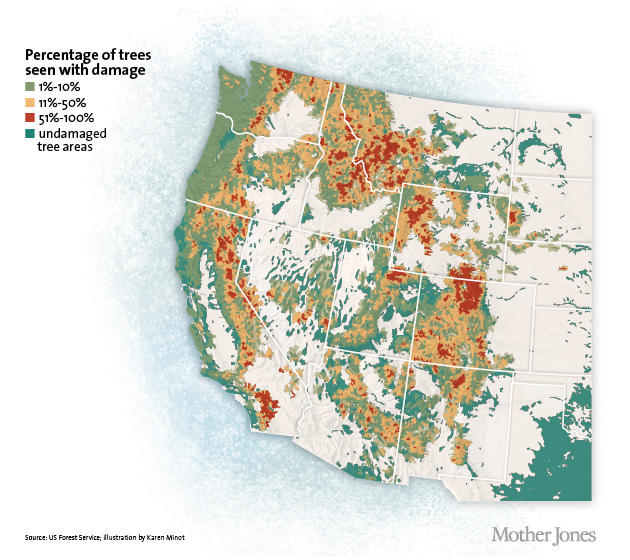

BEETLEMANIA

From 2000 to 2014, bark beetles destroyed large swaths of forests in the American West—and they’re not done yet.

So Western forests right now are crippled by both drought and insects—but does that mean insect epidemics actually increase the chance of wildfires? Feinstein and the folks at CalFire seem to think so.

But turns out the science isn’t so simple. A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2014 by four University of Colorado researchers examined the belief that the dead trees from mountain pine beetle outbreaks exacerbated wildfires. “Although MPB infestation and fire activity both independently increased in conjunction with recent warming,” they concluded, “our results demonstrate that the annual area burned in the western United States has not increased in direct response to bark beetle activity.” Several other studies, including one of lodgepole pine and spruce trees in the central Rockies, have led to similar conclusions.

This is because the parched and broiling conditions already set the stage for increased wildfires, with or without the beetles. Colorado State University biogeography professor Jason Sibold explained it me this way:

The road is icy, and a truck crashes up here on the road. Well a car crashes back there on the road. The car didn’t crash because of the truck; they both crashed because it’s icy!

So, too, he says, beetles and wildfires “are both occurring because we have hotter, drier, longer summers.” (I should add that at the time, Sibold was talking specifically about Rocky Mountain forests.)

Why does this matter? Well, because as Feinstein’s request makes clear, some people think tree removal projects might help stop beetle infestations and prevent wildfires. But others, like Diana Six and California’s Eric Barber, scientists I profiled in this feature about bark beetles and forest ecology, think that insect infestations have a lot to teach us about climate change—and that spending a lot of federal dollars digging up dead trees isn’t the best way to understand these lessons.

Policy “should focus on societal adaptation to the effects of recent increases in wildfire activity related to increased drought,” argue the researchers of the University of Colorado study mentioned above. And that might include learning to live with both beetles and more fires—rather than trying to prevent them.