This April 18, 2013 aerial photo shows a destroyed fertilizer plant, top, following an explosion in West, Texas.Tony Gutierrez/AP

First came the smoke. The explosion hit 20 minutes later—so massive it killed 15, injured 260, damaged or destroyed 150 buildings, shattered glass a mile out and set trees ablaze. Under stadium lights, the West, Texas, high school football field, home of the Trojans, was transformed into a makeshift triage center.

The 2013 disaster in West, a town of just 2,800, began with a fire at the local fertilizer plant, highlighting safety gaps at thousands of facilities nationwide that use or store high-risk chemicals. It took the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency nearly four years after that to issue a rule intended to prevent such accidents—a move strenuously opposed by industry groups such as the American Petroleum Institute.

Firefighters check a destroyed apartment complex near the fertilizer plant that exploded earlier in West, Texas, in this photo made early Thursday, April 18, 2013.

LM Otero/AP

Just a week after the rule was issued, Donald Trump was sworn in as president. Businesses tried again, asking for a delay of the requirements. This time, they got what they asked for.

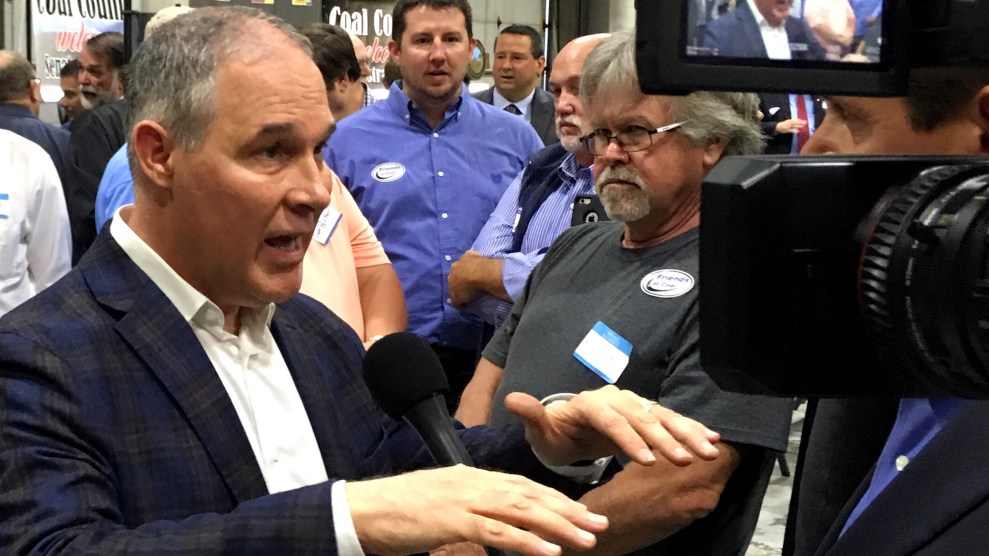

The EPA has granted more than a few private-sector wishes lately under the guise of regulatory reform. Roughly 62 percent of the agency’s “deregulatory” actions completed in Administrator Scott Pruitt’s first year and 85 percent of its planned initiatives match up with specific industry requests, according to a Center for Public Integrity analysis. These changes targeted requirements ranging from air-pollution limits for oil and gas operations to water-pollution restrictions on coal-fired power plants.

Many of these steps followed entreaties from a small number of powerful lobbying groups, including the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the American Chemistry Council and the National Association of Manufacturers.

The EPA, which ignored a half-dozen requests for comment, has said officials are merely reigning in an agency that they assert routinely overstepped its authority. But there is another interpretation. The analysis shows the EPA has been captured by industry, said Alexandra Teitz, a former agency attorney.

“The idea that ‘We are for environmental protection, too, we just choose to do it a different way’ might be plausible if we’d seen anything to support that,” said Teitz, now a senior policy adviser for the Sierra Club. “But we haven’t seen them do anything positive. So, that claim is just a joke.”

Alex Howard, deputy director of the Sunlight Foundation, an open-government group, said the industry successes have come while the EPA is “operating under a veil of secrecy.” The agency has failed to routinely disclose day-to-day activities it previously made public, he said.

While Oklahoma attorney general, Pruitt sued over 14 major EPA regulations and opposed others, including the chemical-safety rule. His legal interpretations tend to align with industry desires: a 2017 New York Times investigation revealed his deep ties to companies and propensity to use their arguments as his own.

In his first six months on the job, Pruitt was scheduled to meet 31 times more often with industry than with environmental or public-health groups, according to a Center analysis last year. The EPA’s internal watchdog is investigating his official travel, including a Morocco trip during which Pruitt promoted natural-gas exports. Asked in a January CBS News interview whether the EPA’s mission is to protect the environment or business, he responded, “It’s neither.”

“Our focus here should be on stewardship,” Pruitt said, adding that “to achieve what we want to achieve in environmental protection, environmental stewardship, we need the partnership of industry.”

Industry’s EPA scorecard

When Trump directed all federal agencies to reconsider existing rules a month into his term, Pruitt seized the opportunity. Regulatory reform would mean “listening to those directly impacted by regulations,” in contrast to the ways the Obama administration “abused the regulatory process,” he said in an EPA news release.

To see who has benefited so far, the Center examined the EPA’s list of completed deregulatory actions and its October agenda for future reform, comparing them to requests made by the private sector in comments to the agency in previous months.

The analysis focuses only on the agency’s stated deregulatory actions. It doesn’t capture other steps taken by the EPA that also went industry’s way, such as the March decision not to ban the pesticide chlorpyrifos, suspected of harming children’s brains. Agency scientists previously recommended prohibiting its use.

In April, the EPA asked the public what rules it ought to roll back. Americans flooded the agency with comments that urged officials to keep environmental-health safeguards intact, while numerous businesses pointed to rules they considered burdensome. The EPA said it drew from those comments to craft its regulatory reform agenda, released in October. But at least three of the four broad initiatives announced by the agency and all nine of the rules identified for reconsideration stemmed from industry requests—85 percent of the EPA’s reform plans.

Reopening a rule allows industry to make the case again that the regulations should be less stringent. Southern Co., for example, previously opposed regulations intended to limit water pollution from coal-fired power plants, asserting the agency relied on “faulty cost-benefit analyses.” Prior to Pruitt, the EPA disputed these claims. Now, it’s taking another look. Southern Co. declined to comment.

The broader EPA initiatives give industry a chance to fundamentally alter the way the nation fights pollution. The agency committed, for example, to evaluating the cumulative employment impacts of its environmental regulations, in response to business requests. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which didn’t reply to emails asking for comment, wrote last May that failing to properly analyze job impacts “stacks the deck against the possibility of producing a good regulation.”

Corporate influence is also apparent in at least 13 of the 21 actions the EPA has taken since Pruitt became administrator on Feb. 17 of last year. Six of these actions delayed, rescinded or reopened for consideration major regulations—wins for business interests. For instance, the agency delayed through May 2018 stricter requirements to protect people applying certain toxic pesticides, a move supported by companies such as Bayer Corp. Another seven industry victories came on narrower issues; manufacturers of wood products, for example, won a deadline extension to meet emission standards.

Industries didn’t always get what they wanted, of course. In part that’s because not all companies are on the same side of every issue. For example, the National Association of Manufacturers and other business groups that oppose the Clean Power Plan, the Obama-era rule aimed at limiting planet-warming pollution from the U.S. power sector, were pleased when the EPA said it would consider a repeal. Microsoft and Apple, on the other hand, supported the regulation in federal court.

Deregulation’s impact

Many companies and trade organizations say their outreach to the EPA is no different than in previous administrations. Some are employing the same arguments they used during the Obama era, including assertions that small environmental gains are coming at an outsize cost to business.

“We have lost the critical balance in our federal environmental policies between furthering progress and limiting unnecessary economic impacts,” the National Association of Manufacturers wrote to the EPA last year. The group didn’t respond to the Center’s requests for comment.

The Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers’ members supported the EPA taking a second look at limits set for greenhouse-gas emissions from light-duty vehicles “to let the facts dictate the outcome,” wrote spokeswoman Gloria Bergquist. She added, “We are not prejudging the results.”

These reviews will aid the public, companies said. “A vibrant U.S. manufacturing base that helps American companies compete globally and keeps jobs here at home is what we all want,” wrote Laura Toole, a spokeswoman for General Motors.

But Teitz, the former EPA lawyer, said Pruitt is pushing agency norms. It’s not unheard of for new administrations to take another look at regulations that aren’t yet in effect, or even those that are, she said. But this EPA is reversing rules companies already must follow at an unprecedented rate, she said, causing confusion for officials in the field and leaving the public under-protected.

That, public advocacy groups and states such as New York and Massachusetts say, is exactly what has happened with the chemical-safety rule, delayed through February 2019. Since the rule was finalized in the waning days of the Obama administration, more than a dozen accidents, leaks, explosions and fires occurred at facilities that would have been covered by these new requirements, according to the Sierra Club. At least eight people died. More than 40 were injured.

A federal court will hear arguments about the delay in March. Industry opponents of the rule say in filings that it would cost companies money without providing benefits to the public. A Louisiana security official, in a court document filed by Oklahoma and 11 other states that support the rule delay, said that allowing it to take effect could expose chemical facilities to terrorism threats because of new disclosure requirements. (Military experts opposing the delay have said the rule would improve national security by better informing first responders.)

Whichever way the court rules, it likely won’t affect West, Texas. The town hasn’t replaced its fertilizer plant and has no intention of doing so, said John Crowder, a local pastor.

“The community would just not welcome that kind of business,” he said. It took nearly five years for West to rebuild, he noted, work that was just completed last month “to a collective sigh of relief.”

Crowder is no great fan of regulation. Now, though, he sees a need for more oversight.

He doesn’t know much about the requirements the EPA enacted and then put on ice, so he can’t say whether they would avert tragedies like the one in West.

“But if there were a rule that could prevent it,” he said, “I can’t imagine a valid reason for delay.”