When Julia Spicher Kasdorf pulled off Pennsylvania’s Route 15 on her way upstate in 2012, she noticed something she’d never seen before. Across the highway, by the restaurant where she and her husband stopped for lunch, helicopters dangling strange pendants were hovering over the mountainside. Kasdorf, a poet and English professor at Pennsylvania State University, asked her server what was going on. “Those guys are here because of fracking,” the waitress said. Oil and gas companies were doing seismic testing for a new pipeline.

Kasdorf grew up in central Pennsylvania surrounded by dairy farms. She’d seen the way coal mining had ravaged the state’s southwest, but this destruction was new. Determined to keep an open mind, she began seeking out stories from people affected by fracking. Her curiosity turned into a six-year project and a collaboration with documentary photographer Steven Rubin that culminated in their recent book, Shale Play: Poems and Photographs from the Fracking Fields. Her conversation at a roadside restaurant inspired the opening poem, “Fry Brothers Turkey Ranch with Urbanspoon and Yelp Reviews.” Here’s a snippet:

The young waitress says last winter they didn’t have to lay

Anyone off. The older waitress says the gas just helps out a bit:

On farms around here, you see a new tractor or truck,

Someone’s put up a garage or painted his house. Look,

Over in Dimock, their water was bad before the gas came.

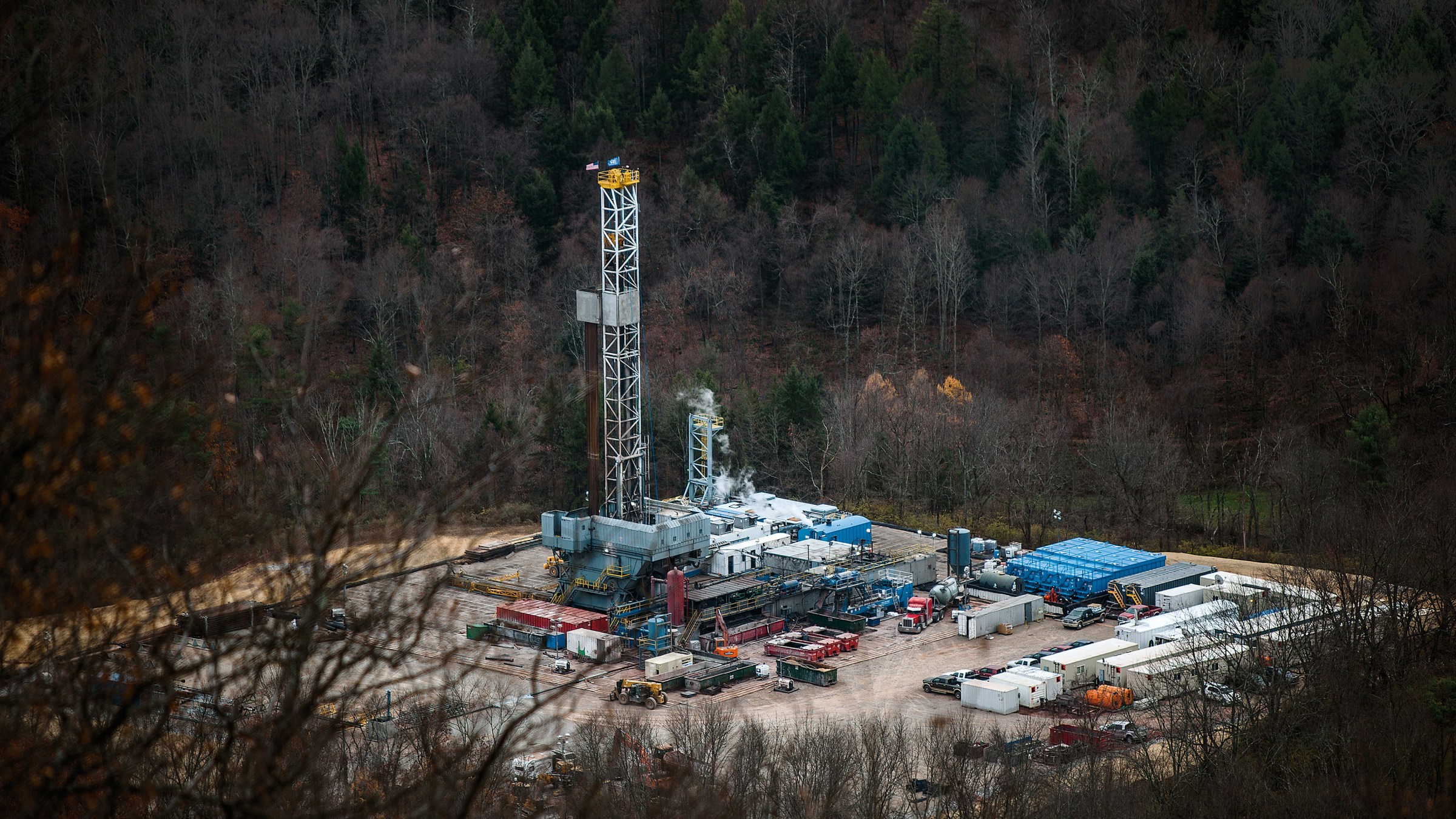

Laid-off workers and students training for shale gas careers visit a Marcellus Shale rig in Greene County in August 2012.

Steven Rubin

Gas-processing gear on a well pad inside Tiadaghton State Forest, Lycoming County, July 2014

Steven Rubin

Fracking, or hydraulic fracturing, is a process for extracting oil and natural gas. Water, sand, and chemicals are pumped deep into the earth at high pressure in order to crack up ancient shale rock and release natural gas. Pennsylvania sits atop one of the world’s largest natural gas fields, the Marcellus Shale, and as of May 2017 was host to 10,097 active fracking wells, according to the state Department of Environmental Protection.

Since the boom began in 2008, fracking has boosted Pennsylvania’s economy with new jobs and investment. But it has also transformed the rural landscape and introduced a host of environmental and public health concerns. The industry has an exemption from the Safe Drinking Water Act and does not have to disclose the chemicals it uses—even though fracking has been linked to high levels of carcinogens in groundwater.

In her university town, State College, Kasdorf was cloistered from the realities of fracking. As she began her research, however, she became aware of the discord between rural residents she spoke with, who saw fracking as a lifeline in poor communities, and her friends in East Coast cities, who questioned why Pennsylvania would allow extraction companies to destroy the state’s natural environment. “I was really determined to keep an open mind,” Kasdorf says. “My impulse was to defend rural people for whom making a living has become increasingly difficult. If fracking means you can keep your farm, am I going to stand in judgment about that? I didn’t know.”

A wastewater tank at a well pad in Lycoming County whose operator, Inflection Energy, has been cited for repeated violations, including the spillage of some 63,000 gallons of toxin-laden water into a nearby creek

Steven Rubin

Residents of Fayette County protest the construction of new pipelines in August 2015.

Steven Rubin

Kasdorf follows a long line of American poets, such as Muriel Rukeyser, Charles Reznikoff, and poet laureate Tracy K. Smith, who have based work on witness and documentation. In Shale Play, Kasdorf draws from court transcripts, letters, and legal documents. Her role, she says, is to select details and language from everyday experiences to highlight their significance. “Americans have always needed help gaining access to their feelings and using their feelings intelligently to make meaning,” she explains.

But Kasdorf doesn’t see herself as an impartial reporter. She lives just 30 miles from where she was born, in a county that lies partially over the Marcellus Shale. As she learned more about the industry, she began to notice mountainsides being quarried for gravel to be used upstate on new roads and well pads. Her daughter once pointed to a dry-cleaning delivery van and asked sarcastically whether it too could be involved in fracking. In her poem “Hot Flash,” Kasdorf reflects on her growing rage:

I can be driving on a highway and it flies

Across my face like flames over dry grass.

“Sometimes I would just get so sad,” she says. “I sat in those hearings and I would collect fragments of what was said in order to tell a story. And obviously that story is entirely skewed by my experience.”

Nonetheless, Shale Play is a collage of voices, drawing in the testimonies of activists, residents, industry lawyers, and workers.

We’re not the gas company; we just lay the pipeline.

I make sure the pipe’s good, the joints are welded right.

Kasdorf explores the nuances and tensions of her home state without allowing any one perspective to dominate.

Workers clean up after a day of spray painting gas well pads throughout Moshannon State Forest in July 2012.

Steven Rubin

Route 22, Westmoreland County, August 2012

Steven Rubin

Despite the power of the fracking industry and the damage already done to Pennsylvania’s rural landscape and communities, Kasdorf remains optimistic. “I don’t want people to feel defeated,” she says. “There was a kind of ferocity and resilience in the people I met, who were fighting with whatever tools they had to try and get to the bottom of things, often against great odds.”

Roughly 50 new wells were drilled in Pennsylvania every month last year, according to industry analyst Imre Kugler. But in April, a Pennsylvania appeals court issued a landmark ruling that redefined some fracking as trespassing. The fracking company’s appeal was rejected in June, and the decision may set a precedent that could curb industry reach. Left unchecked, some experts believe more than 47,000 new fracking wells may be drilled in Pennsylvania by 2045.

“These companies have no concern for the people and places they are using,” Kasdorf says. “We must protect our own people and places from the violence of this kind of exploitation and destruction. And we must devote our resources to developing sustainable energy sources rather than letting multinational corporations make our decisions for us.”

Colby Perrotta and his daughter view the remains of the Donora-Webster Bridge in Washington County. The 107-year-old truss bridge, which makes an appearance in one of Kasdorf’s poems, was demolished in 2015 after repairs or replacement were deemed too costly.

Steven Rubin

This article has been updated.