This story was originally published by Wired. It appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

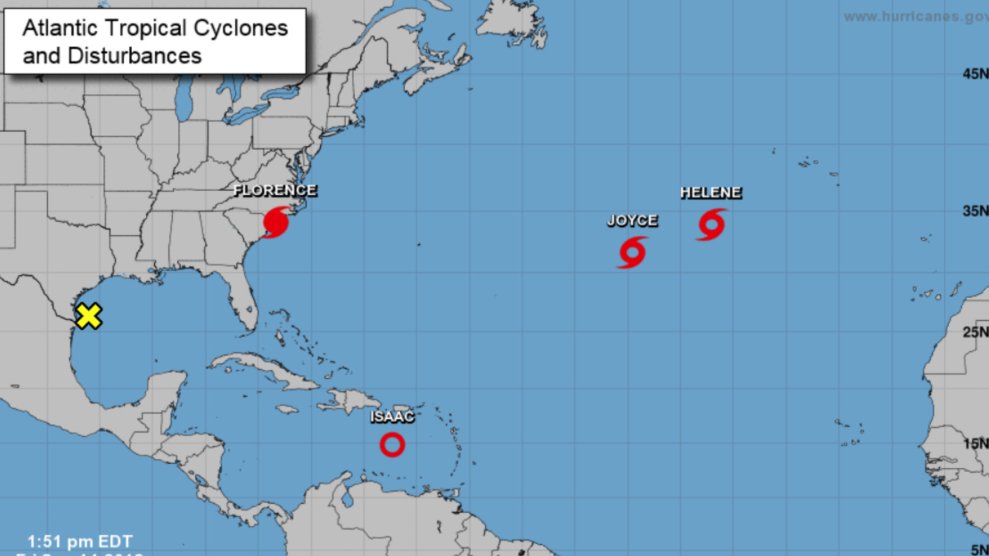

The map looks terrifyingly unfamiliar. Not because of the outlines of the continents; those are comforting in their hooks, tails, splotches, and whorls. It’s the storms. Across the globe’s tropics right now, seven superstorms are swirling over oceans. Hurricane Florence is butting into the Carolinas on North America’s southeastern coast. Tropical storms Helene, Isaac, and Joyce are hovering over the Atlantic like jets stacked on approach to Charlotte. Tropical cyclone Barijat is breaking up as it makes landfall at the Gulf of Tonkin while the Philippines and the rest of southeast Asia girds itself for Super Typhoon Mangkhut.

So, fine, sure, it’s hurricane season. Stormy weather, yes, but climatology said this was going to happen. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has said that science doesn’t know if a warming planet will have more hurricanes, but its assembled researchers do agree that what hurricanes happen will be worse. More intense wind, more rain, parked for longer over coastal cities unprepared for 100-year-storms that now come once every five years instead.

Still, though, a map of a planet with semi-permanent storms around its belt, with a violently churning equator…that starts to look otherworldly. It’s more like the planet-spanning white storms of Saturn, or the swirling atmosphere of Neptune. It’s the sign of a planet in the throes of change, and those changes don’t look good for the future.

Humans are used to the idea of some parts of their homeworld being all but uninhabitable. The arctic regions, even as they lose more and more of their icy expanses to a warmer atmosphere, are essentially no-go regions without intense scientific support. Yes, there are scattered settlements above the Arctic Circle, and some of the bases in Antarctica are technically permanent, in that there are humans there year round, even in the permanent darkness of austral winter. But no human lives in Antarctica, and even temporary visits require protective gear and technical support. Parts of the world’s deserts are all but uninhabited, and researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry have argued that some climate change models put the hottest daytime temperatures in the Middle East and North Africa above survivable levels for humans.

To be clear, scientists tend to dismiss the idea that climate change and other human interventions could render the entire planet uninhabitable. “This is, of course, nonsense,” emails Christopher McKay, a NASA planetary scientist who studies terraforming and life in extreme environments. “What is certain is that the coming changes will be very, very inconvenient to human society and be of enormous cost to human infrastructure. Fires, floods, sea level, heat waves, etc … Although a cynic might say that the Earth overall will benefit in direct proportion that all things human are decremented.”

It’s true that an absence of people in the region might be a boon for all the other living things; editing people out of a landscape tends to make that landscape healthier in the end, if the people didn’t poison it or burn it down before they left. If people can’t live in the tropics anymore, that might increase the biodiversity of everything else there. “A dispassionate observer would ask the question: would the total biodiversity on Earth be higher before climate change or after climate change?” McKay says. “My off-the-cuff intuition is that total biodiversity on Earth would be higher after.”

That won’t be of much comfort to the people living in the tropics, of course. And that change is already happening. US government scientists have warned that millions of people are going to have to leave the atolls of Micronesia by mid-century—just 15 years away!—as climate change raises sea level and floods their islands. As usual, climate change affects the poorest people disproportionately.

Still, though, that’s not “uninhabitable.” In fact, the people who study the possibility of life on other worlds talk about grades of habitability—somewhere else might have even more diversity than Earth can currently support, or could support before humans started mucking about with things. “Using this astrobiological definition of habitability, climate change on Earth today is likely to affect how habitable our planet is. However, even the worst-case scenario won’t make the planet uninhabitable for all forms of life. That’s the positive part,” says Jack O’Malley-James, an astrobiologist at Cornell University. “The negative part is that what we’re doing to the planet is making it less suitable for our own survival. Human civilization has depended upon millennia of fairly stable and predictable climate conditions.”

That’s what we don’t have anymore. The hallmark of the Burning World is more extreme weather at less predictable intervals. Hurricanes can do more damage due to rainfall and storm surge than high winds. People build along coastlines and in low-lying areas, covering the ground with impermeable concrete and asphalt, magnifying the effects of storms; in many ways, cities are giant machines for moving water away from buildings, but under hurricane conditions, the water overwhelms the machine.

When that happens more than once in a while, it should be hard to ignore. When it’s happening in more than one place on Earth at the same time, it’s even harder. What that belt of swirling storms girdling the planet’s midsection says is that the climate is not changing; it’s that the climate has changed. None of the countries on the map are undiscovered. The storms show exactly where we’re headed, and which parts of the world may not belong to humanity any longer.