The temperature has been dropping all morning, so by the time we reach Adam Chappell’s cornfield at the edge of the tiny town of Cotton Plant, Arkansas, it’s in the 30s. Cold for the Delta. Heavy clouds press down on a border of maple and oak trees. I follow Chappell into the field, where we pause amid piles of corn husks and a few abandoned mustard-color cobs. It’s December, and harvest is almost over, yet neat rows of oat grass, fernlike vetch, and radish leaves poke up through the detritus in a medley of growth and decay.

“I bet you my earthworms are down about a foot,” Chappell says through a coppery beard, his large hands hunting for warmth in the pockets of his sweatshirt. “You could probably dig ’em up yesterday, but right now it’s too cold. This place is covered in earthworms. And it didn’t used to be.”

Chappell’s 100-acre field once looked like his cousin’s across the road, an empty stretch of tilled dirt about as appealing to an earthworm as a parking lot. He used to clear his fields after fall harvest, leaving them barren all winter. But about a decade ago, after his farm’s battle with herbicide-resistant pigweed left him and his brother on the brink of bankruptcy, the fourth-generation farmer had a revelation after a late night of scouring YouTube. He phased out the herbicides and instead left the stems and stalks in the field and scattered rye seeds among them to grow through the winter.

His neighbors called it “farming trashy,” implying he was too lazy to clean up his field before planting it in the spring. Yet Chappell observed how the rye fended off the pigweed and shielded his soil so microbes could multiply underneath the protective canopy. He soon shifted almost all his land from conventional to regenerative farming, an approach that focuses on replenishing the soil’s nutrients without relying on synthetic and mined fertilizers.

Chappell says his yields haven’t changed much but he now makes more profit on every acre because he spends less on equipment, water, herbicides, and synthetic fertilizer. This season, he purchased 75 cows to munch down the oat grass and vetch and fertilize the soil before he plants it with cotton. Ten years into his regenerative experiment, the switch has reinvigorated his farm and saved him from financial ruin.

What he didn’t expect is how these tweaks would become the center of a privately funded, tech-amped venture to rescue the American agriculture industry and slow climate change in one fell swoop. Standing next to Chappell today are four representatives from Indigo Agriculture, a sizable ag-tech startup that’s betting it can boost his profits by paying him to draw carbon dioxide out of the air and store it in the ground.

Adam Chappell stands in his field of radishes, hairy vetch, and oat grass—cover crops that help sequester carbon dioxide.

Andrea Morales

Scientists estimate the earth’s soil holds two to three times more carbon than the entire atmosphere. That’s a good thing, because cars, planes, factories, and farms churn out CO2 at astounding rates. If farmers could coax their fields to suck up more of the gas and deposit it underground in the form of organic carbon, it could go a long way toward mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. The benefits don’t stop there: Increasing soil’s carbon content also protects against erosion and increases biodiversity.

The idea of carbon farming is gaining traction. As part of the 2015 United Nations climate change conference, the French government launched an initiative to encourage countries to increase the carbon sequestered in their soil by 0.4 percent a year. In February, Rep. Chellie Pingree (D-Maine) introduced the Agriculture Resilience Act, which would immediately sign the United States on to the French plan and take other steps to restore eroded soil; House Democrats drew on Pingree’s legislation for their climate crisis “Action Plan,” released in late June, which dedicated a chapter to investing in agriculture as a climate solution. And in his “Plan for Rural America,” presidential candidate Joe Biden promises to make the United States’ agricultural sector the first in the world to achieve “net-zero” emissions, in part by increasing payments to farmers for carbon farming through an existing conservation program.

As the US government dithers, the private sector is springing into action. Last June, Indigo announced its plan to sink a teraton (1 trillion metric tons) of carbon dioxide into cropland around the world. Farmers who tend at least 300 acres and were enrolled in Indigo’s carbon marketplace by the end of last year would be guaranteed $15 for every metric ton of carbon dioxide they capture. Companies hoping to offset emissions associated with activities like business travel, energy production, and data storage—or at least seeking a greener image—will be able to purchase credits on Indigo’s carbon exchange for a yet-to-be-determined price.

It’s a bold scheme. And it may be impossible. Some experts believe the soil will never absorb as much carbon as Indigo claims. And some doubt a carbon marketplace can gain enough traders to keep the price of the credits high enough to inspire farmers to change their ways. But Indigo—armed with some of the country’s leading soil experts, agribusiness consultants, and biotech veterans—is forging ahead. Paying farmers to switch to regenerative agriculture “is the most optimistic thing I know about in regard to climate change,” says David Perry, the company’s CEO, and it has the possibility “to fundamentally change farming for the better.”

When Indigo’s representatives caught wind of Chappell’s experiment in regenerative farming at the No-Till on the Plains Winter Conference in early 2019, they invited him to meet with their team in Memphis. Later that year, Chappell signed up to participate in the company’s nascent carbon exchange.

More than 5,000 farmers have joined him so far, Perry estimates. One of them is Ben Riensche, who grows corn and soybeans on 18,000 acres near Jesup, Iowa. He had watched market consolidation and industrialization gnaw at the profits of his family’s fifth-generation farm: There was always a new pesticide or fungicide that could only be paired with an endless stream of patented seeds. “I realized any time a new technology was offered, it would never make me more money,” he tells me. “The more I listened to what Indigo had to say, their mission to disrupt agriculture started making a lot of sense to me.”

Riensche is not the only farmer desperate for a new way of doing business. Growers the nation over face an uncertain future as crop prices have sagged, unpredictable weather disasters have surged, and retaliatory tariffs from President Trump’s trade wars have sent ag markets into chaos.

Much of rural America has been foundering since long before Trump took office, something Chappell knows all too well. He gives me a tour of Cotton Plant, population 595, whose main thoroughfare is lined with shuttered stores and buildings with caved-in roofs. Someone has scrawled the word “blood” in black spray paint on a boarded-up shop. An Elvis look-alike smiles down from a vintage cigarette ad on the door of the only convenience store, a relic from an era when the town prospered. Today it’s struggling. Chappell grew up here but now resides about an hour away in a suburb of Little Rock. “As the older generation dies, there’s nobody new coming in,” he says. “There’s nothing to support people here anymore. It’s just a dried-up Delta town.”

Regenerative farming is buzzy: Whole Foods predicted it would be one of 2020’s top food trends. “Regenerative farmers, who focus on soil health, are the new organic farmers,” wrote New York Times food correspondent Kim Severson in her preview of 2020’s eating fads. Last year, General Mills announced it would partner with farmers to drive the adoption of regenerative practices on 1 million acres of farmland by 2030, and plastered the face of North Dakota soil health champion Gabe Brown on a Wheaties box. Chipotle’s charitable arm promotes regenerative practices, too.

The term “regenerative” may have first been used in the context of farming by organic guru Bob Rodale in 1984. Yet even three decades later, no one can agree on its exact definition. Growers tend to refer to a set of five practices that unify the approach: cover crops, crop diversification, reduced or no tillage, reduced chemical and fertilizer application, and rotational livestock grazing. Currently, there is no certification program for products made specifically on regenerative farms. A group including Patagonia, Dr. Bronner’s, and the Rodale Institute, an organic farming nonprofit, released the framework for a regenerative organic label in 2018. But the certification is not yet publicly available, and it’s broad, requiring commitments to “social fairness” and animal welfare on top of soil health management.

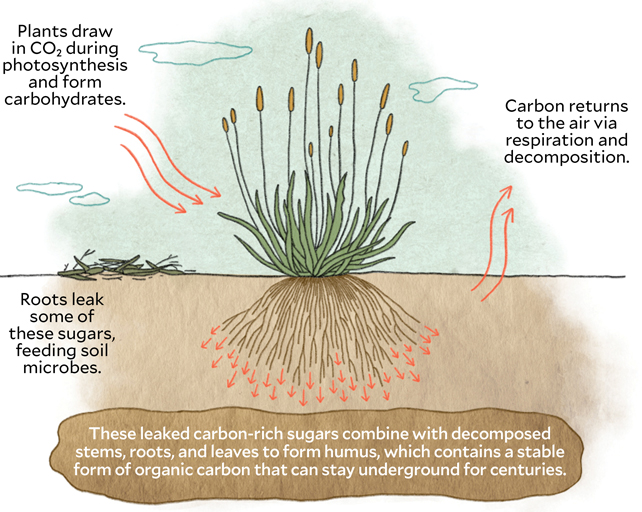

What scientists can agree on is that boosting the health of soil—making it friendlier to industrious bacteria and fungi—helps it trap carbon dioxide. Carbon always cycles around in the atmosphere, oceans, and land; sequestering it in the earth locks it up so it’s released back into the air more slowly. When plants absorb carbon dioxide, they transform the gas into sugars via photosynthesis. Some of those plant carbons are used to grow stems and leaves, and some leak out through the roots. Soil microbes help convert both plant carbon and decomposed plant matter into humus, the cakey dark stuff we associate with dirt. It contains a highly stable and long-lasting form of organic carbon that won’t seep back into the atmosphere for centuries.

An acre of farmland, according to Indigo, has the potential to trap the equivalent of 2 to 3 metric tons of carbon dioxide annually. If so, a farmer who participates in the company’s carbon marketplace could enjoy an extra $30 to $45 per acre every year. (An average acre of corn fetched around $650 in 2019.) The market hasn’t officially opened yet; company reps have spent the past year signing up farmers—who have submitted 19.8 million acres of land and counting—with the hopes of launching the exchange during the second half of 2020. While a shift to regenerative farming will likely require some initial startup costs, growers will only make money on the exchange if they successfully nudge their land to increase its carbon sequestration.

Chappell will start with Indigo’s Carbon Cup, a friendly competition between enrolled farmers to see whose soil contains the highest absolute value of carbon. The national winner can look forward to a cash prize, and state winners receive a trip to an Indigo conference.

The day I visit his farm, Indigo has sent Hannah Fite, a Memphis-based field operation specialist, to test the carbon levels in a field of Chappell’s choosing. Before Indigo came along, Chappell wasn’t in the habit of checking because each test costs roughly $60. I expected an elaborate process involving a syringe or a chemical bath. But it’s actually pretty straightforward: Fite uses an iPad to pick a randomized point generated by Indigo’s software. When she locates the spot, she pulls out a long metal probe that looks like a drum major’s baton, plunges it into the dirt, and pulls up a moist column, which she dumps into a plastic bag to send to the lab.

It’s relatively easy to test a plug of soil for carbon. What’s less simple is predicting how much carbon dioxide a farmer may lock up across thousands of acres of land with varied soils over many years. Indigo’s Perry says the company will combine the results of its randomized soil tests with satellite data and machine learning to improve the accuracy of measuring the carbon load of large tracts of farmland.

But as scientists with the World Resources Institute pointed out recently, the factors that influence how much carbon soil can retain and for how long are “enormously complex.” When Indigo announced the goal of sequestering a teraton of carbon dioxide, it assumed that farmers tending the world’s 3.6 billion cultivated acres could all increase the carbon content in their soils from 1 to 3 percent. Experts say that’s a stretch. That the initiative “is substantially overestimated is maybe a polite way of saying it,” says Keith Paustian, a soil ecology professor at Colorado State University who served as a lead author on papers for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in the early 2000s. Jonathan Foley, executive director of the climate think tank Project Drawdown, puts a finer point on it. “The claims being made by some organizations and companies right now are pretty wild,” he wrote in an email, “and I think somewhat irresponsible.”

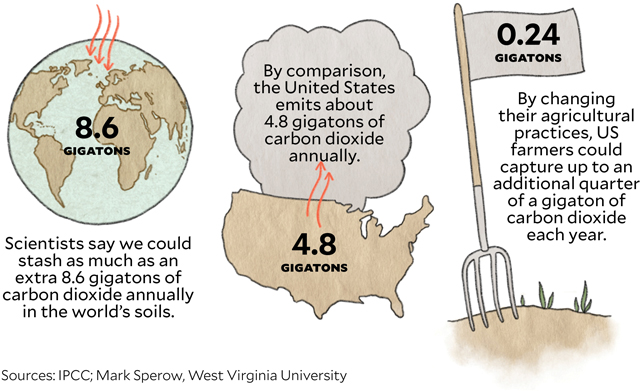

Studies suggest he might be right. While Indigo predicts farmers can absorb 2 to 3 metric tons of carbon dioxide per acre every year, measurements by Ohio State University soil science professor Rattan Lal found maximum rates of just 0.7 tons of CO2 a year per acre of US cropland. Jonathan Sanderman of the Woods Hole Research Center used a massive historical dataset to estimate that the world’s soil has lost 133 gigatons of soil carbon (the equivalent of 488 gigatons of carbon dioxide) over the past 12,000 years due to agricultural land use, about as much as we’ve lost by cutting down forests during the same time frame. In his most optimistic scenario, we could hope to recapture 103 gigatons of carbon dioxide on existing farmland by around 2040—about a tenth of Indigo’s teraton goal. In the 2019 IPCC report on land use, researchers posited that the world’s soils could stash away up to 8.6 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent a year, or nearly double the United States’ 4.8 gigatons of carbon dioxide emissions in 2019. Yet all of these estimates “assume that everyone around the world adopts new behavior and new technologies,” Sanderman says. “Not only adopts it, but does a good job of adopting it. That’s a very tenuous assumption.”

Indigo’s entrepreneurs think a private marketplace will incentivize that adoption. Carbon markets that reward growers for “ecosystem services,” as they’re known, aren’t new, but they haven’t taken off in the US. In 2003, the Chicago Climate Exchange became the country’s first voluntary and legally binding cap-and-trade market. But it collapsed in 2010 after a sudden surplus of offset credits caused their value to crash. California’s state-run cap-and-trade market provides farmers with grants to support climate-friendly practices, but the applications are onerous, and the program’s proponents say the current funding needs to increase about threefold to make a real dent. “Nobody’s paid farmers to do this before,” Perry says. “Once we start to get incentives for farmers to maximize this, I expect that we’ll find all sorts of ways of sequestering more carbon per acre than we currently know how to do.”

So far, the millions of acres in Indigo’s marketplace make it the largest project of its type. A Seattle-based company called Nori recently launched a private carbon exchange using blockchain technology, but it is working with a smaller group of farmers. Indigo has “so much money, they are able to play that disrupter role,” says Stephen Wood, a scientist at the Nature Conservancy who specializes in soil. “It makes a lot of people really uncomfortable, but it also could just be the catalyst for change that a historically not functioning market might need in order to start working.”

Eric Deeble, policy director of the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, points out that public programs to incentivize farmers for soil-friendly practices do exist; the Conservation Stewardship Program, for instance, funds farmers to plant cover crops. There’s an ongoing debate among environmentalists and policymakers, he explains, about whether the best strategy going forward is to continue to give farmers money to plant the kinds of crops and use the techniques we know lead to healthier soils, or to create a marketplace and measure the amount of carbon farmers sequester and turn it into tradable credits. The latter strategy, capitalists argue, might lead to more rapid adoption.

But private marketplaces come with certain consequences, Deeble notes. “If you are looking for a high rate of return on a carbon offset investment, you will find the lowest price with the highest value assigned, and then you will find the very biggest farms from whom you can buy those credits.” That does nothing to make sure that historically underserved producers get to participate. While the US government has a troubled history with racial equity in farming, some progress has been made; for instance, the department of agriculture at least has a civil rights division. “If you take away the safeguards that come with federal engagement,” Deeble says, “it could be calamitous for BIPOC farmers and highly diversified, sustainable farmers.”

Indigo’s Memphis office is a 12-story brick building abutting the AutoZone ballpark; employees on its east side enjoy a view of the Memphis Redbirds’ home games. At least in the days before the pandemic, a lustrous cafeteria offered free lunch and a snack area stocked with granola bars and hummus. Upstairs, the walls of the open-plan workspace display close-up photos of cotton plants and tips of wheat stalks. A mural next to the elevators spells out the company’s mission: “Harnessing nature to help farmers sustainably feed the planet.”

Indigo emerged from the Boston-area venture capital firm Flagship Pioneering in 2014. The company had planned to sell seed coatings that “complement a plant’s natural processes,” according to Indigo co-founder Geoffrey von Maltzahn, and stimulate its growth while reducing the need for synthetic fertilizer and herbicides. Buoyed by successful trials and hundreds of millions in funding, the company broadened its focus by using data to “improve farmer profitability” and dismantle the bureaucracy bogging down a slow-moving industry. “We don’t think a one-part solution will solve all the problems in agriculture,” says Allie Evarts, the PR manager taking me around the Memphis office. “We need to use a systems approach.”

In addition to Indigo Carbon, that approach now includes Indigo Marketplace, which lets growers put their grains directly on the market and score a premium for, say, non-GMO or organic varieties. (Like Etsy for corn and soybeans.) “We call it decomoditizing agriculture,” Evarts says. There’s Indigo Transport, a logistics app that connects growers and shippers with a pool of drivers for more efficient delivery. (Like Uber for agricultural truck drivers.) Indigo Acres, a pay-per-acre consulting service with a free tier, provides farmers with agronomic tools and grain testing insights. (An Acorns for growers.) Indigo Atlas draws on satellite data to produce a dynamic map of the world’s food system, offering daily forecasts of how weather patterns affect growing conditions. (Like Google Maps for plants.)

Indigo boasts more than 1,000 employees spread across its US and global offices, and counts among its executives veterans from the agribusiness giant Syngenta and tech platforms Wayfair and StubHub. In early 2020, Indigo scored $200 million of venture capital financing, bringing its total raised capital to $850 million.

As with many burgeoning tech firms, Indigo’s value proposition seems somewhat elusive. Is the company mostly profiting off its microbial seed treatments, or will brokering its carbon market prove its most profitable venture? Evarts, Indigo’s spokesperson, said only that the company delivered value through a combination of offerings. She did specify that the grain marketplace and Indigo Carbon have seen the most recent growth, and once the carbon exchange is up and running, “we expect revenue to increase dramatically as global interest in and demand for carbon credits and offset programs surge.” CEO David Perry thinks this capital will help jolt the stagnant farming industry. “There could be billions or hundreds of billions of dollars flowing into agriculture from sources that don’t exist today,” he says. “I think that’s really exciting.”

Project Drawdown’s Foley sees a dark side to this optimism. He supports paying farmers for regenerative practices and has included that strategy in his NGO’s list of solutions to beat climate change. But he smells whiffs of what he calls the “Silicon Valley hype cycle”: “Ooh, here’s a bunch of people wandering into a field and saying, ‘We’re going to disrupt something and change the physics of it.’ Then a couple of months or years go by and everybody realizes, ‘Oh my god, this is overhyped, and it’s not going to deliver.’ And then we throw the whole thing out.”

Given the climate crisis, Foley wonders, should massive banks and companies, the primary buyers of offsets in a carbon market, be allowed to pay their way out of their sins instead of making real efforts to reduce emissions? Indigo’s Perry won’t name any of the potential buyers he’s in talks with, but he points out that in January, JetBlue announced it planned to offset all emissions associated with its domestic flights. Microsoft buys a lot of carbon credits, he says, as does—gulp—Shell. A 2019 analysis by the Climate Accountability Institute revealed that 20 fossil fuel companies are responsible for more than one-third of all greenhouse gas emissions. Royal Dutch Shell was seventh on the list of top polluting oil companies.

“The first thing we need companies to do, big time,” Foley says, “is reduce their own damn emissions.”

Whether or not they deliver climate salvation, it’s clear that farmers need some kind of revolution. “It’s not a good situation out there,” Chappell says when I reach him again in January, after rain delayed the end of his cotton harvest until New Year’s Eve. The season had been wet and unpredictable. And Trump “pretty well decimated a market that it took ag 20 to 25 years to put together,” Chappell says. It’s not just the trade wars. “The morale in the ag industry is bad. It’s cost of production. Land rents.” Farm bankruptcies have multiplied, as have calls to suicide hotlines in farm country.

Working on regenerative agriculture, by contrast, has given Chappell confidence. He’s one of only a handful of growers in the mid-South with expertise in this type of farming. Indigo invited him to become a research partner; the company will run experiments on his land as part of what it calls “the world’s largest agricultural lab.” Some experts think agroforestry practices such as grazing livestock in stands of planted trees can do a better job of pulling carbon into the soil than crops alone, but these practices are far more popular in other countries. Chappell intends to experiment with a 400-acre wooded area he leases. He’ll plant it with perennial grasses and run cows and goats through to manage the mulberry brambles.

Chappell has signed up all of his acres to be measured for potential credits tradable on Indigo’s carbon exchange, and he plans to diversify his revenue stream with profits from the market.

“I’ve never been involved with anything like Indigo. It’s so fast-paced. They’ve got a lot of big ideas, and I like a lot of them,” he says. “Are they going to be practical in the real world? I don’t know. I hope so.”

This story has been updated since it originally appeared in our May+June 2020 issue.