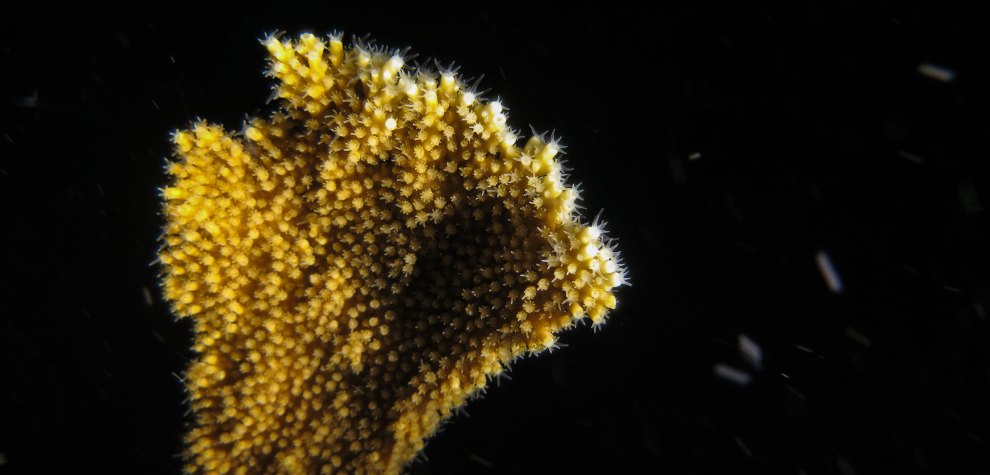

The elkhorn coral is one of the most endangered corals in the Caribbean and the Florida Keys.Kristen Marhaver

This story was originally published by Hakai Magazine and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Wearing a navy-blue polo neck emblazoned with the Florida Aquarium logo, Keri O’Neil hugs a white cooler at Miami International Airport. “Coral babieeeeees,” she says, before letting out a short laugh. Relief. The container holds 10 plastic bottles teeming with thousands of tiny peach-colored specks. Shaped like cornflakes and no more than a millimeter in length, they are the larvae of elkhorn coral, an endangered species that is as characteristic to the reefs of the Florida Keys and the Caribbean as polar bears are to the Arctic or giant sequoias to Sierra Nevada.

With the larvae kept at 27 C inside their insulated cooler nestled in the trunk of her car, O’Neil drives back to the Florida Aquarium in Tampa, where she works as senior coral scientist at the aquarium’s Center for Conservation. Once there, the larvae begin their metamorphosis from free-swimming specks into settled polyps, the beginnings of those branching, antler-like shapes that define this species. O’Neil and her colleagues provide everything the coral needs for a strong start in life: warm water with a gentle flow, symbiotic algae that find a home inside the coral’s cells, a soft glow of sunlight, and some ceramic squares “seasoned with algae” that act as landing pads for the larvae.

The transformation of larvae into polyps was the final step in a coral breeding project that began on the shores of Curaçao, an island off the coast of Venezuela, in the summer of 2018 and involved a cadre of conservationists and scientists who each specialize in one specific stage of coral development. From collection of eggs during mass spawning events to the cryopreservation of sperm, and from fertilization to larval growth, every step had to go swimmingly for the project to have any chance of success.

“It’s like the most stressful relay on Earth,” says Kristen Marhaver, a coral scientist at the Caribbean Research and Management of Biodiversity Foundation in Curaçao, who helped start this relay race by collecting eggs during a nighttime dive at a reef that’s a 45-minute drive from her laboratory. As O’Neil was picking up her coral “babies” in Miami, a second team of scientists at Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium in Sarasota, Florida, received its own. The pressure on both labs was immense. To fail now would be to drop the baton just before the final straight.

But, if anything, their efforts were too successful; hundreds of larvae settled as translucent and fragile blobs of tissue (each a single polyp) and then started to divide, branching into the clear waters of their shallow, open-top tanks. Elkhorn coral grows an average of five to 10 centimeters per year, a bamboo-like pace for corals in general. To stop them becoming entangled, O’Neil had to cut, separate, and move her colonies to different paddle pool–sized tanks over the course of the next year. “We almost ended up with a six-foot-by-four-foot solid piece of elkhorn coral made up of 400 different individuals,” she says. “They were just outgrowing the tanks.”

A juvenile elkhorn coral colony, about six months old, gets its start in a lab at the Florida Aquarium in Tampa. The eggs came from coral in Curaçao and the sperm from coral elsewhere in the Caribbean—populations that, under normal circumstances, would not have mixed in the wild.

Kristen Marhaver

The rows of coral in O’Neil’s tanks are a window into a former world. The reefs of the Florida Keys were once dominated by elkhorn coral. Visiting these islands that curl southward from Florida like the tip of a bird of prey’s beak, biologist, conservationist, and writer—most notably of Silent Spring, but also of several books on the ocean—Rachel Carson peered into the shallows using a “water glass,” an instrument akin to a glass-bottom bucket. Through this simple portal, she saw great stands of “trees of stone,” a forest of coral. Today, after decades of disease, coastal development, and bleaching, over 95 percent of the state’s elkhorn coral have been lost.

This population isn’t just depleted in number, like a forest that’s been felled, but is also impoverished from within. Some reefs in the Keys descend from a single individual that has reproduced via fragmentation—bits break off the parent coral and start a new colony. This mode of reproduction allows corals to spread, but without the genetic mixing that comes with sex, these clones are more susceptible to disturbances such as disease.

The coral larvae raised by O’Neil at the Florida Aquarium are different; they are the product of sperm and egg, a shuffling of genes, and the growth of genetically unique clumps of coral. Reintroducing them could provide a boost to the coral’s genetic diversity—a quick stir to the gene pool—and could save a denuded ecosystem. Their reintroduction could also spell its doom.

Hidden inside the genetic code of the Florida Aquarium’s coral is a map of an atypical origin: the eggs collected from Curaçao were fertilized using sperm from the Caribbean, including Florida. Although the same species (Acropora palmata), these coral populations would never breed in the wild. The distance between the two is hundreds of kilometers and contains the island blockade of the Greater Antilles—an impossible journey for any sperm. The coral housed in the Florida Aquarium are the products of human hands, the latest addition to a recent—and often controversial—trend in conservation known as “assisted gene flow,” shuttling existing genetic diversity to new places.

Elkhorn coral spawn only once a year, triggered by the full moon, but estimating the exact time and date of the spawn is tricky. Scientists in Curaçao dove for more than 40 nights before the elkhorn coral they were monitoring finally released their eggs.

Smithsonian National Zoo

No hands have offered more assistance to these coral than those of Mary Hagedorn, senior research scientist at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, who is based at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Hagedorn flew to the Caribbean to guide this project from start to finish. It is her research that made this work possible. Since 2004, she has developed cryopreservation techniques that can freeze coral sperm and—just as importantly—keep them fertile upon thawing.

Although cryopreservation has been used for IVF in humans and other mammals for decades, it’s only in the last few years that other coral conservationists have adopted Hagedorn’s techniques for coral sperm. At a time when these methodologies are most needed, Hagedorn’s work has matured into a solid science, says Tom Moore, a coral restoration manager at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration at the time of this project and now in the private sector. “I think we’re going to start seeing a lot more of this done in the course of the next few years.”

Without the option to freeze sperm, coral conservationists have been forced to work within the few hours these sex cells remain viable. In Florida, Moore says, scientists from the Lower Keys would drive north to meet colleagues from the Upper Keys and swap sperm samples on the side of the road, fertilizing eggs there and then before the sperm stopped swimming. With the option to freeze sperm using liquid nitrogen, however, samples can be transported long distances—from Florida to Curaçao, for example. Then, when eggs are collected from the reef, the sperm can be thawed and used in concentrations that make fertilization most likely. Hagedorn’s work opens up new possibilities that, just a few years ago, were largely ignored.

Kendall Fitzgerald, left, and Claire Lager, of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, use cryopreservation techniques to conserve coral as part of a global biorepository.

Smithsonian National Zoo

Self-funded for many years, Hagedorn’s research was nearly stopped altogether in December 2011. Her savings had run out and funders didn’t seem to see the potential of her work. “I was a month away from closing my lab,” she says. Then she received an unexpected call from the Roddenberry Foundation, a philanthropic organization set up in memory of Gene Roddenberry, the writer of Star Trek. Since Hagedorn’s work fit the criteria for bold and unique science, the foundation wanted to fund her research for five years. Since then, her work has grown to include frozen larvae, frozen coral symbiotic algae, and frozen coral fragments, and it has been adopted by labs around the world. To help her cryopreservation methods spread, Hagedorn runs workshops and shares her techniques freely; the instructions to build her equipment can be downloaded and then manufactured with a 3D printer.

As with IVF in humans, coral fertilization is not a perfect science. In a study published in 2017, Hagedorn and her colleagues showed that fertilization rates from frozen coral sperm are significantly lower than from fresh sperm, roughly 50 percent versus over 90 percent. And these figures were based on coral that lived as neighbors on the same reef. The researchers wanted to increase genetic diversity in the future (through assisted gene flow), but it was still unknown whether populations that had been isolated for thousands of years could produce viable offspring, especially after their sperm had been frozen. The idea to breed elkhorn coral from the Florida Keys with those from Curaçao was the most extreme test yet of Hagedorn’s methods. It was a moonshot for coral conservation, says O’Neil. “We wanted to do something that had never been done before.”

Marhaver thought that they had a five to 10 percent chance of success. To have hundreds of healthy coral now sitting in tanks barely crossed her mind. Conservationists are more attuned to the vibrations of endangerment, extinction, and loss. To have a moonshot succeed is unfamiliar territory. With the impossible now possible, the next hurdle is moving from the lab to the ocean, a leap that not everyone is comfortable with.

As in medical practice, the first rule of restoring ailing ecosystems is primum non nocere, “first, do no harm.” And what concerns Lisa Gregg, program and policy coordinator at the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC), the organization that decides the fate of the Florida-Curaçao coral, is that they aren’t suited to the local conditions of the Florida Keys, a place that Carson referred to as having an atmosphere that is “strongly and peculiarly [its] own.”

These islands are formed from sedimentation, while those of Curaçao and the eastern Caribbean are founded on volcanic activity. Plus, the Florida Keys also have their own unique combination of problems, from infectious disease to coastal development, and from hurricanes to coral bleaching. “We have a lot of problems here,” says O’Neil. “And it is quite likely that the corals that are still alive in Florida after everything that’s happened to them are probably the ones that are best suited to living in Florida and providing offspring that may be capable of surviving in Florida.”

If Curaçao genes were introduced, they might lead to lower rates of reproduction, shorter life spans, or lowered resistance to local diseases. Imperceptible at first, such “outbreeding depression” can slowly weaken a population, generation by generation. To introduce genes that haven’t experienced the same history could be a ratchet toward extinction.

The risk of such outbreeding depression is very low, however—a doomsday forecast for Florida’s reefs, many conservationists think. “I’m not so concerned that there’s a huge risk of the Curaçao [genes] causing a major detriment to the native Florida population,” says Iliana Baums, head of marine conservation and restoration at the University of Oldenburg, Germany, who has studied elkhorn coral since 1998. “But that’s based on my knowledge of the literature for other species and modeling and so on. I don’t have any direct evidence for that.” Direct evidence would require reintroduction, a catch-22 of conservation; the very thing that is controversial and potentially dangerous is also the route to understanding.