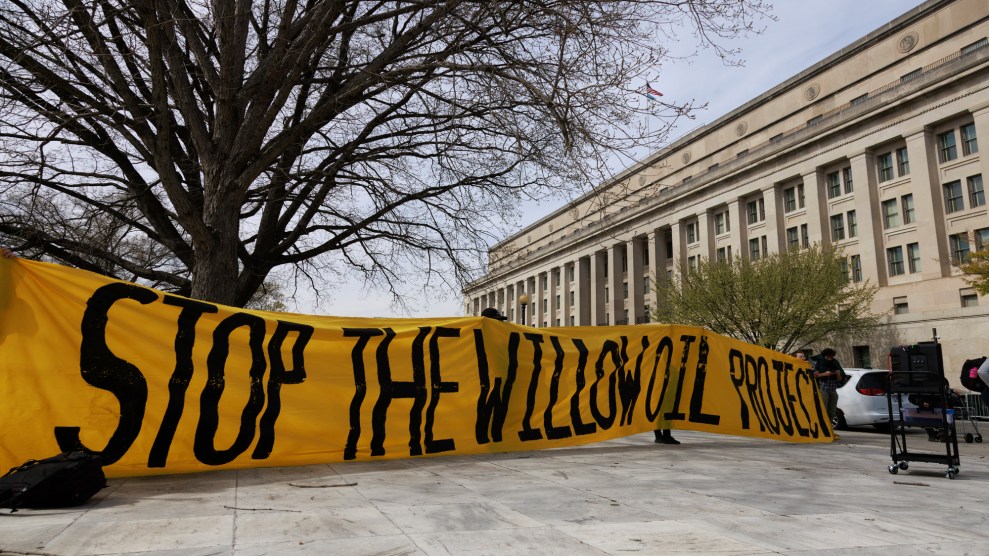

Bryan Olin Dozier/NurPhoto/AP

President Joe Biden is facing the inevitable political fallout from his approval of the Willow Project this week, after a federal judge declined to halt construction on ConocoPhillips’ $8 billion oil drilling venture in the western Arctic. Willow, one of the most contentious fossil fuel infrastructure projects since the Dakota Access and Keystone XL pipelines, was formally approved by Biden on March 13.

In a ruling on Monday, US District Judge Sharon Gleason rejected requests by environmental and Indigenous advocacy groups for an injunction that would have temporarily stopped the project from moving forward on public land. Biden’s decision to approve Willow has been particularly controversial given his campaign promise that there would be “no more drilling on public federal land, period.”

“If you’re going to stop developing new sources of oil and gas, what better place than one of the last pristine, most phenomenal ecosystems on Earth, which is the North Slope of Alaska. It’s the Serengeti of North America,” said Patrick Parenteau, an environmental law professor at the Vermont Law School and a former EPA regional counsel.

Willow would generate 576 million barrels of crude oil over the next 30 years, emitting more than 250 million metric tons of carbon dioxide. Before the project’s approval, the Interior Department had expressed “substantial concerns” about Willow, including its “greenhouse gas emissions and impacts to wildlife and Alaska Native subsistence.”

To soften the blow, the White House paired its rubber stamp of the venture with a plan to safeguard more than 13 million acres of the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska from future oil and gas development and prohibit offshore drilling in 2.8 million acres of the Arctic Ocean. But many environmental groups believe these concessions aren’t enough, especially with less than six years left to mitigate the worst effects of climate change in an area of the Arctic warming four times more quickly than the rest of the world.

In approving Willow, the Biden administration indicated that ConocoPhillips had the legal right to drill in the region because the company has held lease rights to the area since the 1990s. If the administration canceled those leases, the decision would have likely prompted a lawsuit that could have resulted in billions of dollars in damages awarded to ConocoPhillips, administration officials told the New York Times. White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre told reporters days after the approval that the president “kept his word where he can by law” and that Biden “has done more on climate change than any other president in history.”

But environmental advocates haven’t bought into Biden’s reasoning. “This was a presidential-level decision,” Parenteau said. “No court ordered this. This is the president. He owns this one.”

Parenteau argued that any legal costs from canceling the leases would “pale in comparison” to the social and environmental costs of approving the project. According to an analysis by climate nonprofit Friends of the Earth, remedying the long-term damage brought on by Willow could cost between $20 to $80 billion—more than the potential $8 to $17 billion in revenue the project is expected to bring in for the federal government and Alaska.

In March, two separate lawsuits were filed challenging Willow by groups including Earthjustice, the Center for Biological Diversity, and Sovereign Iñupiat for a Living Arctic. The organizations argued that the Department of the Interior’s environmental assessment of Willow was flawed and asked Gleason to pause construction on Willow while the suit moved forward. Though Gleason had blocked the Willow Project once before in 2021, citing a lack of a thorough environmental assessment, she declined to do so this time around, writing that construction wouldn’t cause “irreparable damage” to the plaintiffs.

Gleason’s decision allows for the immediate building of roads, pipelines, and a gravel mine that is scheduled to begin construction in the last three weeks of April. It’s alarming news for residents of Nuiqsut, the Iñupiat community living closest to the Willow Project, who are already dealing with the adverse effects of existing oil and gas drilling sites in the North Slope. Only last year, a ConocoPhillips gas leak prompted some worried residents to evacuate. The community has expressed several concerns with Willow’s potential impact: “sick fish, signs of starvations in caribou, and toxic air quality directly caused by oil and gas extraction within their homelands,” in addition to potential public health effects on people living nearby.

At the same time, in a state that has historically relied on income from energy and gas, some Alaska Native communities and state politicians have expressed support for the project because of its potential economic benefits. In an op-ed for the Hill, Democratic Rep. Mary Peltola, the first Alaska Native congresswoman, argued that Willow would provide thousands of short-term jobs that would support Alaskans. “We need a plan for a real transition that does not leave our most vulnerable people freezing in the winter in places like Noatak, Alaska,” Peltola wrote. “We need a bridge to fill the gap. The Willow Project can be part of that bridge.”

Still, ConocoPhillips’ environmental track record has advocates concerned that Willow is just a disaster waiting to happen. In 1989, residents of Ponca City, Oklahoma, sued the company after finding black slime in their basements from a ConocoPhillips refinery. They claimed pipeline leaks from the nearby refinery poisoned the water in the area, causing birth defects, cancer, respiratory problems, and other illnesses. ConocoPhillips paid more than $20 million in a settlement that included buying up or destroying more than 400 homes near the site. Since 2015, the company has also paid $11 million to settle a lawsuit after it was accused of failing to monitor hazardous materials in California and a roughly $40 million in a lawsuit over contaminated groundwater in New Jersey. (The company did not admit fault in any of the settlements.)

Although dubiously designated the fourth most “environmentally responsible” out of 120 oil, gas, and mining companies by the Arctic Environmentally Responsible Index (AERI) in 2021, ConocoPhillips found itself in 13th place in a list of the top polluters in the world by the Guardian in 2019, and in 2015, was named the “leakiest” gas company by Climate Wire.

This reputation doesn’t inspire confidence, especially for an undertaking as huge as Willow, which will move oil across swaths of land in an area where—because the permafrost is rapidly melting—the company would have to install “chilling” devices to stop oil rigs from tilting in the ground. And the potential for multimillion-dollar lawsuits hasn’t deterred ConocoPhillips in the past.

“Penalties are not a very effective treatment for Big Oil,” Parenteau said. “And I think their track record proves it…But the penalties are just the cost of doing business. Even though these penalties sound like a lot of money for violations, but not when you’re talking about the potential for recovering billions of dollars over 30 years.”

Halting fossil fuel infrastructure projects after development has begun isn’t unprecedented, and it may still be possible for Willow. In 2021, Biden rescinded the construction permit for the Keystone XL pipeline because of its potential environmental impact. And in 2020, a federal judge shut down construction on the Dakota Access pipeline after it had already begun construction. Though the environmental groups weren’t granted a preliminary injunction to halt construction on Willow, the lawsuit is moving forward, and Earthjustice and the Center for Biological Diversity have vowed to continue fighting the project.

“We have no more time to be greenlighting projects that will lock in fossil fuel production from our public lands,” Erik Grafe, deputy managing attorney at Earthjustice, said in an interview. “We are also continuing to advocate for better decisions by this administration that will align its public lands policy with its climate goals.”