Traffic lights are out of service on a street in San Juan, Puerto Rico, early Thursday, April 7, 2022. Carlos Giusti/AP

This story was originally published by Grist and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

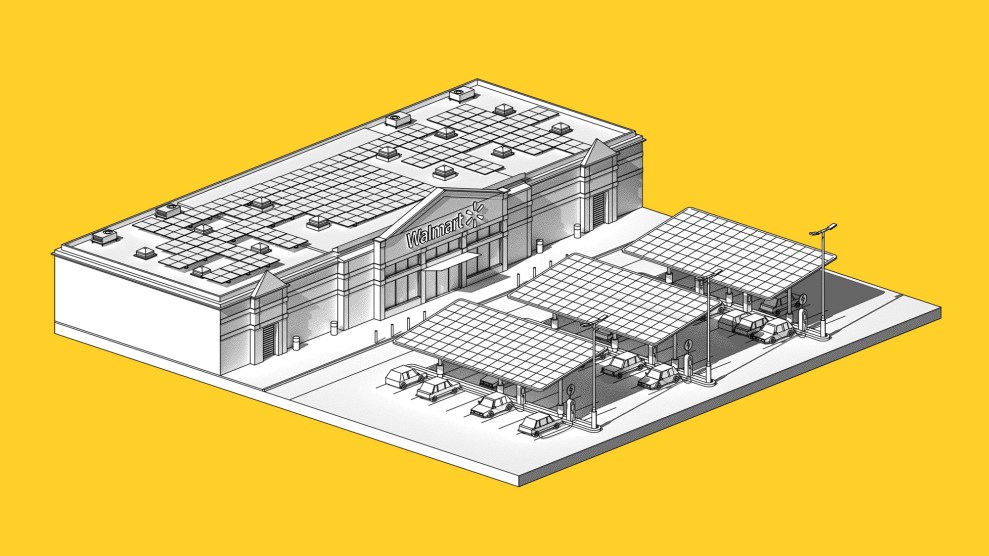

The Department of Energy announced last week that it will provide nearly half a billion dollars to install rooftop solar and battery back-up systems on the homes of some of Puerto Rico’s most vulnerable residents. The funding could cover the installation of as many as 40,000 photovoltaic systems, providing a measure of energy security to an archipelago long burdened by frequent and prolonged blackouts.

The program, which Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm outlined at an event in San Juan, is part of the $1 billion Puerto Rico Energy Resilience Fund that Congress approved last December. The fund is intended to provide reliable and affordable energy to the highest-need households, many of whom endure power outages daily or weekly.

After Hurricane Fiona left the entire archipelago without power last September, President Biden put the Department of Energy in charge of a multi-agency effort to overhaul the US territory’s energy system, which is in disrepair and depends upon fossil fuels to generate 97 percent of its electricity. The campaign includes a two-year study to find the most effective path toward Puerto Rico’s goal of achieving a zero-emission grid by 2050, streamlining approval processes, and deploying the billions of dollars allocated for Hurricane Maria recovery that have not yet been spent.

The effort will take years, and in the meantime, Puerto Ricans suffer from the persistent anxiety of not knowing when the power will go out next. In the last year, the number of rolling blackouts there exceeded the North American utility standard by 570 times, according to DOE.

“That should be seared into our souls,” Granholm told a group of federal and local officials, industry leaders and community members on Monday, “because that is unacceptable, and that is what we are trying to fix.”

The $450 million that Granholm announced will be directed toward the lowest-income households. It will be reserved for people who are medically vulnerable and depend on plug-in medical equipment, and those who live in “last-mile” communities, mostly located deep in the main island’s central mountain ranges. After Maria, some of these municipalities lacked power for nearly one year.

“To say they’re remote and rural communities does not do justice to their circumstances,” said C.P. Smith, executive director of Cooperativa Hidroeléctrica de la Montaña, which has installed microgrids in rural areas in the central mountains. “They might have one road coming out of there, no wider than a small car. They’re the last to get power because after a storm it’s not just about restringing wires, it’s about repairing a road to get a truck up there to restring the wires.”

The focus on “very low-income” families will supplement an already robust solar industry in Puerto Rico. Photovoltaic panel and battery installations skyrocketed after Hurricane Maria, and some 3,000 installations are done monthly now. More than 85,000 households have PV systems. But the poorest households have not been able to participate in the transition according to PJ Wilson, president of the Solar and Energy Storage Association in Puerto Rico, and are burdened by electricity prices at least 50 percent higher than the national average.

“We’re very glad that it appears that their intention is to focus these funds on the people who are truly so low-income or disabled that they have no other viable way to acquire solar and storage,” Wilson said. “Hopefully this helps lift people out of poverty.”

Most of the money will go directly to solar installation companies, nonprofit energy providers and electric cooperatives that will install, own and maintain the systems. An innovative $3.5 million “Solar Ambassador” program will determine which households receive them. The ambassadors will go into communities and identify households most in need—a stark contrast from other widely criticized first-come, first-served programs in Puerto Rico.

“No one ever pays for that ground game part of community organization for energy development,” said Smith. “The ambassador program will help get the message out there and identify people who we know are having a hard time.”

Another notable aspect of the program is its third-party ownership model, which takes the onus off households to maintain the systems. Installers must manage and maintain them for at least 20 years and replace worn-out batteries, and the program allocates consumer-protection funding to hold solar companies accountable. Installers will cover just 5 percent of the cost, making it easier for nonprofit energy providers and small cooperatives to participate.

The program’s structure was in large part shaped by a vigorous community outreach campaign led by Granholm. In the last year, she has been to Puerto Rico five times to gather input from Puerto Ricans at town halls and roundtables. A spring visit to the home of a couple in the mountain town of Orocovis, where their son relied on a ventilator to breathe and a small diesel generator was the family’s only lifeline in a blackout, underscored the urgency of the problem, Granholm told Grist in March. “It’s life or death,” she said.

The department incorporated public concerns about paying for repairs, prioritizing those most in need, working with existing community networks, and ensuring equitable access to information about the program and the ability to apply.

Such an approach represents a seismic shift compared to what Puerto Ricans have experienced from local and federal governments, especially in the time after Hurricane Maria caused $90 billion in damage and claimed more than 4,000 lives, according to Charlotte Gossett Navarro of the Hispanic Federation.

“What we have unfortunately experienced with a lot of the recovery money in Puerto Rico is it goes straight into the hands of the state government, and they design their programs behind closed doors,” said Gossett Navarro. “There has not been any meaningful space for communities to help design the programs, and what results is programs that are announced just full of errors in how they will be executed, and the people you want to benefit are not benefitting from it.”

Those doing the hard work of bringing solar to Puerto Rico were buoyed by Granholm’s announcement, though a few questions remain on the details of the program. “This has all the good elements, we’ll see what the stew is like when you cook them all together,” said Jorge Gaskins, board president of Barrio Eléctrico, a nonprofit energy provider serving residents across Puerto Rico.

Gaskins and other nonprofit and industry representatives said they want to know more about who would pay for the 20-year maintenance of the systems, as well as how the $450 million can cover 30,000 to 40,000 households. (Systems typically cost about $30,000 per household.) In an emailed response, the department told Grist that the leases would include a “minimal contribution from the homeowner for ongoing maintenance” and that the money is meant to incentivize installations and can be combined with solar tax credits to maximize its impact.

Applications for installation funding and the ambassador program opened Monday and will close on September 18 and 25, respectively. DOE aims to announce recipients in October, and the first systems could be online by next summer.

A second tranche of the $1 billion Puerto Rico Energy Resilience Fund, the details of which will be announced in the coming months, will support energy solutions for multi-family residences.

The accelerated timeline underscores the dire need for reliable, affordable power in Puerto Rico. Heat indices in parts of the archipelago have reached 125 degrees this summer, and hurricane season is just weeks away. Granholm said Monday that every agency moving Puerto Rico toward a resilient and clean energy future must work as quickly as possible. “Our hair should be on fire,” she said.