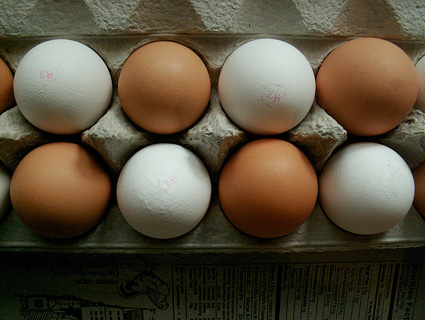

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/rosefirerising/379898756/">rosefirerising</a>/Flickr

Over on the Atlantic site, the food politics writer Jane Black has a thoughtful post on farmers market sticker shock in brownstone Brooklyn.

Confronted at her neigborhood market by the spectacle of $8/dozen eggs—which had sold out, no less—Black frets that “that the ‘good-food-costs-more’ argument is being taken to an extreme that puts at risk the goal of a mass food-reform movement, which is to make good food available to the greatest number of people possible.”

Black goes on to do a bit of analysis on the $8/dozen farmer’s production model and reckons that he probably isn’t just sticking it to Brooklyn yuppies: “It turns out that’s what it costs him to produce his eggs,” because he uses a labor-intensive pasture-based system and feeds his birds organic corn, which is much more expensive than conventional.

So we have a genuine quandary here: A farmer who’s just scraping by while doing the right thing by his land and his birds, charging a price that makes the whole concept of alternative food systems seem hopelessly elitist.

Meanwhile, at my local Walmart in Boone, North Carolina, a dozen eggs will set you back just $1.18. Those 10-cent eggs, of course, are produced in vast, fetid factories, sucking in huge amounts of environmentally ruinous corn and concentrating much more manure than can properly be absorbed into surrounding farmland.

What’s the answer to the dilemma described by Black? Can we eat affordably without destroying the ecological means of production? I doubt it; that is, not as long as our regulatory agencies sit idly while gigantic companies turn abuse—of labor, the environment, and animals—into a business model. How much of a hidden subsidy does big agribusiness reap from our lax regulatory regime, some of which it pockets in profit and some of which it passes on to consumers in the form of stuff like 10-cent eggs and $2-a-pound pork chops?

Ralph Loglisci of the Center for a Livable Future pointed me to a report (PDF), part of the Pew Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Production, that examines that precise question with regard to another product that’s cheap in the supermarket and expensive at the farmer’s market: pork.

Coauthored by Daryll Ray—a University of Tennessee ag economist whose work I revere—the report finds that under current regulations, producing hogs in vast factories is significantly cheaper than raising them on pasture. But if you made the giant hog factories deal properly with the vast amount of toxic waste they produce, the price difference reverses. In other words, a Walmart value-pack of pork chops would cost significantly more per pound than the pasture-raised ones that give you sticker shock at the farmers market.

And untreated toxic waste is only one so-called externality, or unpaid cost, of factory hog farming. Another major one is the rising menace of antibiotic-resistant pathogens, which flourish when you stuff hogs together by the thousands and feed them daily “subtherapeutic” antibiotic doses. Pew reckons that the antibiotic resistance problem adds between $16.6 billion to $26 billion in extra costs to the nation’s annual health care bill. How much more would those Walmart pork chops be if the hog industry had to pay its share of that bill?

What this is telling us is that pasture-based systems—the kind that produced the eggs whose price made Jane Black blanch—are actually a bargain in societal terms: Pay more for food, pay less for ecological and public-health calamities. But that’s cold comfort for millions of families that struggle to put decent food on the the table amid a dreadful economy.

Not hog heaven, but close: Pigs in a hoop house. But the report also points to a third kind of hog production, pictured left: hoop houses that give hogs plenty of room to roam over beds of straw. Their production costs are only marginally higher than those of factory hog farms under current regulations, and they don’t generate massive waste problems or require daily doses of antibiotics. They require much less investment to build than giant confinement buildings, meaning less risk for farmers. In fact, they could be widely distributed on diversified farms throughout the country—which is precisely how hogs were raised before the pork processing industry began in the 1970s to concentrate hog production into a few counties in North Carolina and Iowa. (Go here for a primer on hoop-house hog production; and here for an Iowa farmer’s account of his switch from CAFO to hoop-house production).

Not hog heaven, but close: Pigs in a hoop house. But the report also points to a third kind of hog production, pictured left: hoop houses that give hogs plenty of room to roam over beds of straw. Their production costs are only marginally higher than those of factory hog farms under current regulations, and they don’t generate massive waste problems or require daily doses of antibiotics. They require much less investment to build than giant confinement buildings, meaning less risk for farmers. In fact, they could be widely distributed on diversified farms throughout the country—which is precisely how hogs were raised before the pork processing industry began in the 1970s to concentrate hog production into a few counties in North Carolina and Iowa. (Go here for a primer on hoop-house hog production; and here for an Iowa farmer’s account of his switch from CAFO to hoop-house production).

What’s holding up widely dispersed hoop-house pork farming? Mainly, the vast market power enjoyed by giants like Smithfield. Over the years, they’ve essentially taken over the hog processing business, gobbling up smaller players and shuttering small and mid-sized slaughterhouses. As they’ve gained power, they force farmers either to scale up to huge factory-size operations or exit the business. Millions of small and mid-sized farms have taken the second option since the 1980s. The pork giants’ stranglehold represents yet another de facto subsidy of limp federal regulation: the failure to enforce basic antitrust principles.

Want to eat responsibly produced food without emptying your wallet? Work to free our regulatory agencies from the food industry’s back pocket.