They’re going hog wild in Iowa again. Chart: Des Moines RegisterSince the dawn of the Great Recession, Americans have been eating less meat, including pork. Meanwhile, prices of corn and soy—the main components of US livestock feed—have been high.

They’re going hog wild in Iowa again. Chart: Des Moines RegisterSince the dawn of the Great Recession, Americans have been eating less meat, including pork. Meanwhile, prices of corn and soy—the main components of US livestock feed—have been high.

Lower demand, high feed costs: Basic economics tells us that US factory farms should be cutting back, slowing down, producing less. And that would be a good thing, because as I’ve written so many times before, our style of meat production sucks up huge amounts of resources and creates vast amounts of pollution.

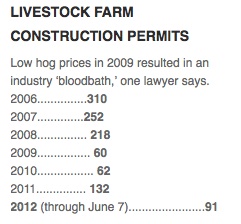

Yet look what’s happening in Iowa, by far the nation’s leading hog-producing state. There, the Des Moines Register reports, there’s been a boom in state-issued permits for new factory-scale hog confinements. As the chart to the right shows, new permits fell off dramatically in 2009, driven down by the low hog prices, but are now charging back up.

Why would the meat industry be investing so heavily in new hog capacity if the economics aren’t working out? Grist food editor Twilight Greenaway proposes an answer: The industry is looking toward a boom in pork exports. Greenaway points to a recent article in Iowa Farmer Today showing that the US pork industry is salivating at the prospect. Recent free trade pacts with South Korea and Colombia, plus an expected one with Panama, will likely boost that number.

Indeed, the pork export explosion is already underway. The industry currently exports nearly 28 percent of of the pork produced in the United States, Iowa Farmer Today reports. According to this recent USDA report, pork exports in the first four months of 2012 jumped 13.5 percent compared to the same period of 2011. The biggest driver was China, with its rapidly expanding demand for meat. Pork exports to China reached 259 million pounds in the first 4 months of 2012*—a 142 percent leap. If present trends continue, China will soon surpass Mexico and Japan as the largest export market for US pork.

And that could happen quickly. According to a hog-industry official quoted by Iowa Farmer Today, the United States produces hogs much more cheaply than its Chinese counterparts—$63 per hundred pounds of animal for US producers vs. $113 for Chinese farmers.

The difference quite likely lies in the degree of industrialization of hog farming in the two countries. In the US, nearly all hog production takes place in factory-scale facilities. Small-scale, diversified farms have been all but wiped out by the consolidation of meat packing, replaced by gigantic confinement operations. Between 1990 and 2010, this USDA report shows, the number of farms that keep hogs has plunged from about 260,00 to about 69,100, and about 97 percent of pork comes from facilities with at least 500 hogs.

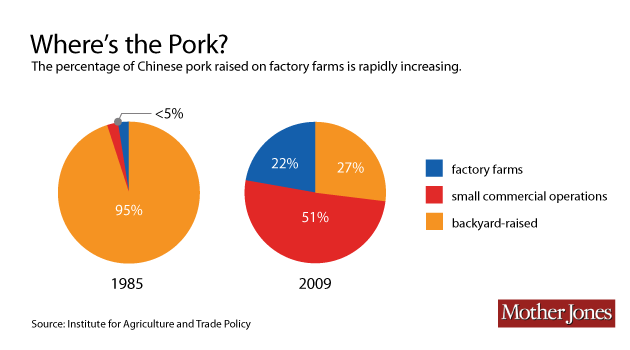

China, too, has made a major push to industrialize farming. As recently as 1985, 95 percent of Chinese pork came from backyard operations distributed across the country, a 2011 report for the Institute for Agriculture and Trade policy found. Today, as the charts below show, 27 percent of hog production still takes place in traditional backyard farming; another 51 percent takes place in small operations with between 50 and 200 pigs. The other 22 percent comes from US-style factory production, in many cases in partnership with US hog giant Smithfield.

Of course, huge operations cut costs by replacing human labor with machines, buying feed in great bulk, and foisting the cost of dealing with massive concentrations of hog waste onto society at as a whole. The mighty US pork machine has much to teach China’s food planners on these topics. A flood of cheap pork imports from the US could be the death knell for what’s left of China’s small-scale hog farmers.

Here in the States, the export boom means that even if we continue eating less meat, we can expect no slowdown in industrial-scale livestock production. Both our poultry and beef industries are experiencing similar export surges. Indeed, the Obama administration has actively encouraged it as part of the effort to double all US exports under the president’s watch. It would be a singular irony if the United States, the most powerful nation on earth, emerged as the place where lax regulations and low wages made it the hog (and chicken and cow) butcher for the world.

Correction: In the original version of this article, the number of pounds said to have been exported at the beginning of the year was incorrect.