<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/76145908@N08/6938972164/sizes/z/in/photostream/" target="_blank">Green Fire Productions</a>/Flickr

I’ve argued often that the food system functions like an economic sieve, draining away wealth. Imagine, say, a suburb served by a handful of fast-food chains plus a supermarket or Walmart or two. Profits from residents’ food dollars go to distant shareholders; what’s left behind are essentially low-skill, low-wage clerical jobs and mountains of generally low-quality, health-ruining food.

But the food system’s secret scandal is that it’s economically extractive in farming communities areas, too—and especially in the places where industrial agriculture is most established and intensive. I first learned about this surprising fact from the Minnesota-based community economics expert Ken Meter, specifically this 2001 study on a farm-heavy region of Minnesota. And now Food and Water Watch, working with the University of Tennessee’s Agricultural Policy Analysis Center, has come out with an excellent new report documenting the food industry’s effect on several ag-intense regions, with the main spotlight on the hog-centric counties of Iowa, the nation’s leading hog-producing state.

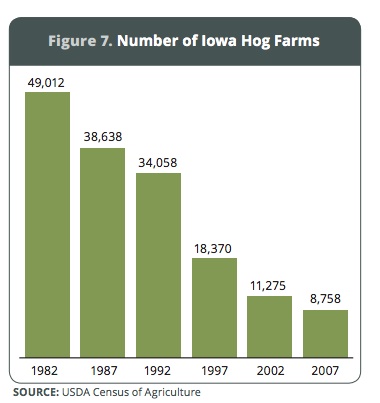

The structure of Iowa’s hog farming went through a dramatic change starting in the early 1980s. As this FWW chart show, first, the number of hog farms in the state declined.

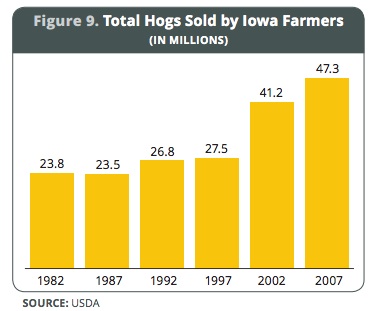

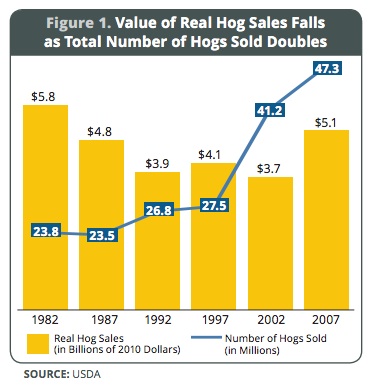

All charts by Food and Water Watch. At the same time, the total number of hogs raised in the state nearly doubled.

All charts by Food and Water Watch. At the same time, the total number of hogs raised in the state nearly doubled.

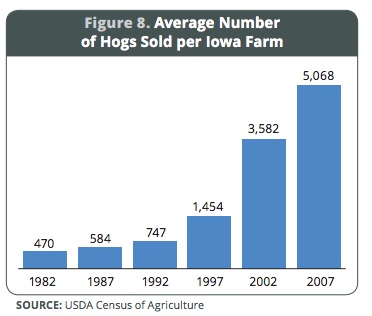

Accordingly, the remaining hog farms scaled up dramatically, growing by a factor of nearly 11 between 1982 and 2007:

What caused this epochal change? According FWW’s analysis, it was driven by the increasing consolidation of hog packing. Packers are the companies that buy hogs from farmers, slaughter them, and cut them into chops, bacon, and the like. In the 1980s, the meatpacking industry began what economists call a consolidation wave—big companies buying smaller companies and consolidating operations into bigger and bigger processing facilities. As the pork packers got bigger and bigger, they were able to use their market weight to force down the per-pound price they paid farmers for their hogs.

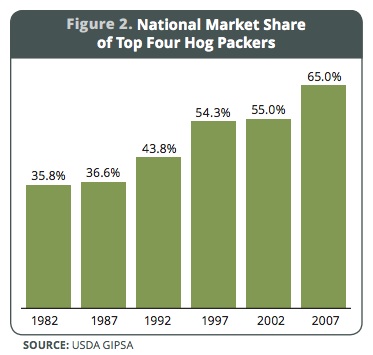

To assess the level of an industry’s concentration, economists use a measure they call “CR4″—the percentage of a market controlled by the four biggest companies. “In most sectors of the US economy, the four largest firms control between 40 and 45 percent of the market,” FWW writes. At CR4 levels above 40 or so, the reports continues, markets start to lose competitiveness—the big firms have power to dictate terms to their suppliers, in this case, farmers. Look at how CR4 has grown nationally since 1982:

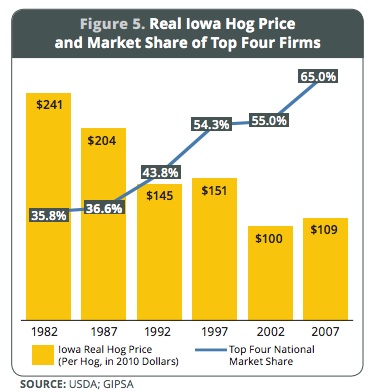

In Iowa, the situation is even more stark. CR4 levels have edged down slightly in recent years, but remain near 90 percent. That means that many hog farmers must either sell to one of the Big Four—Smithfield, Tyson, JBS, and Cargill—or exit the business altogether. As noted above, 80 percent of the farms selling hogs in Iowa in 1982 took the latter route. Most of the rest of them scaled up—and saw the prices paid them by the Big Four plunge. As the next chart shows, the real (inflation-adjusted) price farmers get for each hog fell by more than half between 1982 and 2007.

In Iowa, the situation is even more stark. CR4 levels have edged down slightly in recent years, but remain near 90 percent. That means that many hog farmers must either sell to one of the Big Four—Smithfield, Tyson, JBS, and Cargill—or exit the business altogether. As noted above, 80 percent of the farms selling hogs in Iowa in 1982 took the latter route. Most of the rest of them scaled up—and saw the prices paid them by the Big Four plunge. As the next chart shows, the real (inflation-adjusted) price farmers get for each hog fell by more than half between 1982 and 2007.

Now here’s the kicker. When you look at the state as a whole, Iowa’s hog farmers were bringing in more money, in inflation-adjusted terms, in 1982, when they raised 23.8 million hogs, than they did in 2007, when they raised 47.3 million hogs.

This is a great deal for the Big Four packers—they’re getting nearly twice the pork, for less total money. For the farmers, it’s a different story.

Now, Iowa’s hog farming used to be widely distributed across the state—most farms raised some hogs along with corn, soy, and other crops. As farms either exited hog production altogether or scaled up dramatically, hog farming got more and more concentrated into a handful of counties. You might think that people who live in these hog-centric counties got some economic benefit from the vast scaling up of hog production. At least you’d hope so—as I learned on a 2007 trip through one of those counties, Hardin (report here), it’s no fun to live in industrial-hog country. Such areas are marked by clusters of bleak hog houses, each containing as many as 2,400 animals—as well as fetid, foul-smelling manure cesspools (known as “lagoons”) and horrific periodic spraying of nearby fields with liquid shit rife with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. A recent study from University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill researcher Steve Wing showed that people who live within smelling distance of industrial-scale hog farms have higher incidences of high blood pressure.

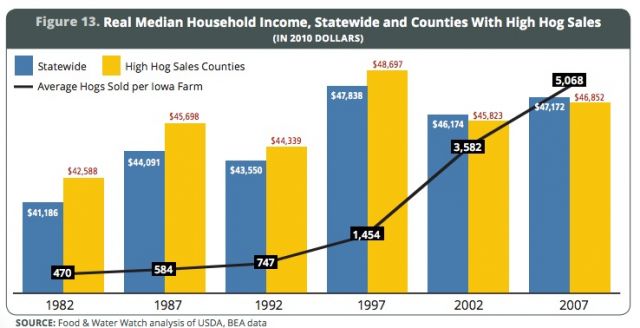

Well, Food and Water Watch found that hog-heavy Iowa counties don’t do better economically than other counties—the opposite, in fact. The next chart compares real median annual household incomes in hog-heavy counties (based on the total number of hogs sold each year) with the statewide average.

Note that in ’82, hog-heavy counties had slightly higher-than-average median incomes. After 25 years of scaling up, that reversed itself. Overall, the state’s average median income rose by 14.5 percent over the time period, while median incomes in the state’s hog-intense counties grew by just 10 percent.

Food and Water Watch also finds evidence of growing inequality in the hog counties—while real median incomes grew by 10 percent between ’82 and ’07, average incomes jumped by about a third. “The rise in real per capita income alongside a less robust increase in median household income suggests that earnings are being captured by a smaller portion of more well-off people in counties with high hog sales,” FWW writes.

Why the dismal economic performance in the counties that house Iowa’s booming pork industry? It costs money to run a big farm, and the larger the farm, the less of those farm expenditures go to local business, FWW found. Large farms buy about a third less per hog worth of goods from local businesses than small farms, the report shows. And that’s a third less money circulating through local economies, building wealth and creating jobs. The study found that for the average Iowa county, the average number of nonfarm local businesses grew by about 30 percent between 1982 and 2007. For the hog-heavy counties, though, the average number of such establishments fell by more than 10 percent.

Not surprisingly, while the average Iowa county saw robust growth in total jobs over that period, for hog-heavy counties, total jobs dropped.

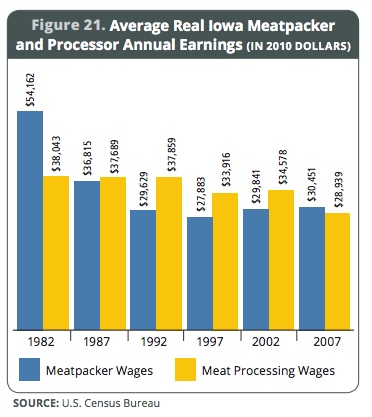

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the economic story for meatpacking and processing workers—the people who slaughter, cut, and package Iowa’s vast annual hog crop. As Ted Genoways’ blockbuster 2011 Mother Jones piece shows in graphic detail, conditions have grown quite grim on the slaughterhouse floor. The following chart looks at real annual earnings for packers (workers who slaughter live animals) and processing workers (people who turn carcasses into sellable products). This is a story of full-on immiseration—what were once middle-class jobs now pay poverty-level wages.

Here’s how FWW sums the situation up:

Counties with more hog sales and larger farms tend to have lower total incomes, slower income growth, fewer Main Street businesses and less retail activity. General employment levels have suffered, wages in meatpacking have declined and farm job opportunities are more difficult to find. In spite of what Big Pork boosters have said, there is little evidence that the trends in Iowa hog production have been good for Iowa’s rural economies.

Now, in their defense, the meatpacking giants often counter that the changes described here are necessary for the provision of cheap food. To deliver you a bountiful supply of pork chops, farmers and workers must be squeezed. But here, too, FWW brings a cold slap of reality. The report finds that when hog prices rise, the pork packers tend to pass on the increase to consumers “completely and immediately”; but when they fall, as they have for much of the past 25 years, the companies tend to pocket much of the difference as profit, passing only some on to consumers.

So, in addition to all the environmental damage associated with factory-scale hog farming, it’s an economic disaster, too—unless you happen to be a shareholder in one of the Big Four pork packers.