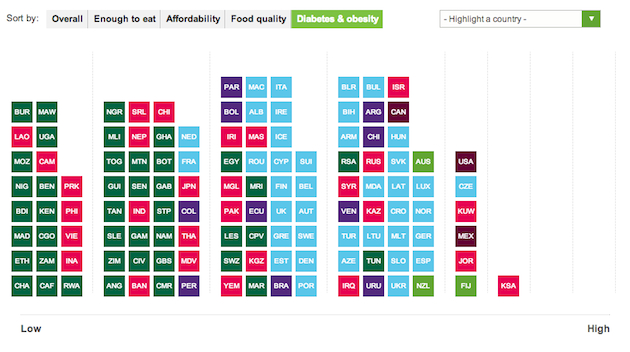

Over the past few decades, it has become possible to speak of a “global food system”—shorthand for the trade patterns, shaped by multinational companies, that move raw agriculture commodities and processed food across borders. Yet as this fascinating new Oxfam study shows, there are still huge differences in people’s experience of food across the globe. Oxfam ranked nations on four criteria: whether food exists in plentiful supply, whether it’s broadly affordable, whether it’s of good quality, and whether it’s causing high rates of obesity and diabetes.

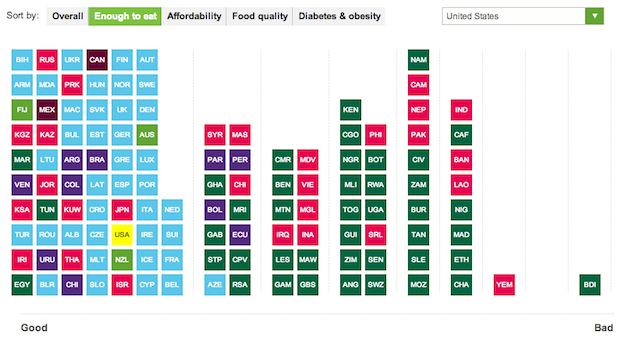

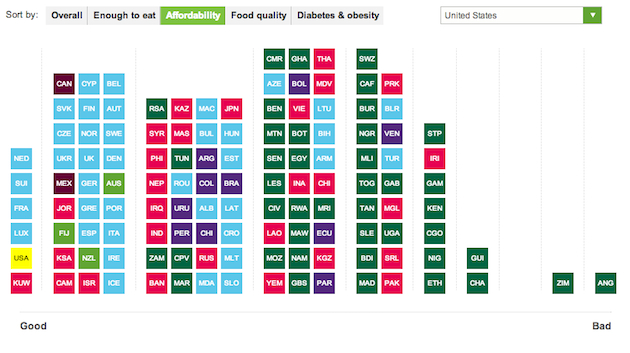

Try playing around with the above interactive tool (note that it functions better in Chrome than in Firefox). Oxfam’s visualization tool broadly groups countries on a scale of “good” to “bad,” but can be confusing when it comes to ranking countries within the same bunches. To get more precise rankings, go to this Excel file.

The overall rankings, which average the four categories and is the default setting of the above tool, tell us something we already know: that Western Europeans enjoy a pretty great food situation, while people living in most African and (to a lesser extent) Asian countries have it pretty bad. The US comes out pretty well, tied with Japan but behind 19 West European nations (as a look at that Excel file shows).

Drilling down a bit, the “enough to eat” metric—which compares rates of malnutrition and underweight children—tells us it’s way better to live in high-income countries like the usual West European suspects and the US than in extremely low-income ones like Zimbabwe, Angola, and Chad. There are a couple of outliers, though. Mexico, Jordan, and Brazil, for example, have a much lower per-capita GDPs than the Western European nations, the US, and Japan, yet it joins them on the “good” end of the scale (GDP numbers here.) It would be interesting to study the food policies of Mexico, et al, to see how they manage to make food broadly available despite relatively low national incomes.

The “affordability” metric—measuring how pricey food is vs. other goods, as well as price stability—tells a similar tale: It largely tracks income (people who make plenty of money can afford plenty of food). It ha a similar set of outliers, too.

The “obesity and diabetes” metric is a kind of mirror image of the previous two: Higher-income countries tend to have higher rates of these diet-related maladies. Here, the US emerges at the high end of the scale, bunched with petro-states like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Again, Mexico and Jordan find themselves out of their income league. But the chart doesn’t quite argue that countries that countries that severely limit malnutrition and make food affordable are doomed to super-high rates of obesity and diabetes. Look at low end of the chart, where you find the Netherlands and France. And the middle, which includes Italy, Denmark, Greece, and other West European nations. These examples suggest that you can create robust food systems that are broadly affordable—without making a huge swath of your population sick and fat.