<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&language=en&ref_site=photo&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&use_local_boost=1&autocomplete_id=&search_tracking_id=Puk9jB98gVUUK6iaYtz99g&searchterm=food%20pyramid&show_color_wheel=1&orient=&commercial_ok=&media_type=images&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&color=&page=1&inline=264882746">Mykola Komarovskyy</a>/Shutterstock

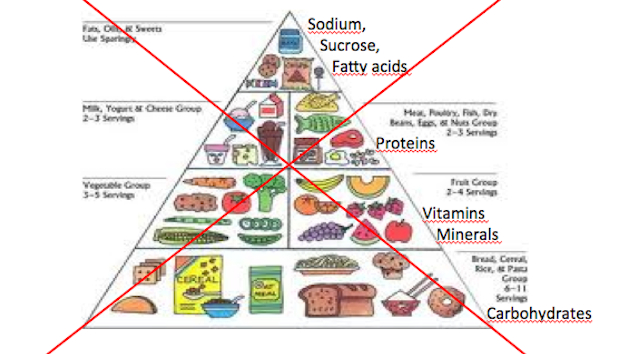

Later this year, the US government is set to unveil its new dietary guidelines—advice on what Americans should eat to stay healthy. The guidelines, once known as the Food Pyramid, are updated every five years and are hugely influential: They affect everything from food labeling and doctors’ advice to school lunch menus, aid programs for low-income families, and research priorities at the National Institutes of Health. They also have some clout globally, with governments in other Western countries often adopting similar nutrition policies.

So how exactly does the US government come up with these guidelines? The process might be less scientific than you’d expect, according to a new investigation in a major British medical journal that suggests Big Food is playing too big of a role in the government’s dietary recommendations.

The guidelines, writes journalist Nina Teicholz in the BMJ journal, are based on a report by the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, a panel of experts tasked with reviewing scientific studies on nutrition. For years, the advisory committee faced criticism about its review process, so in 2010 the US Department of Agriculture created the Nutrition Evidence Library, which set up a system to methodically evaluate scientific research based on a hierarchy of evidence and a transparent grading process.

But in the 2015 report for the new guidelines, the advisory committee said it did not use NEL reviews for more than 70 percent of topics it covered; instead, Teicholz found, the committee used studies by outside professional organizations, including some with backing from Big Food, like the American Heart Association (which she says received 20 percent of its revenue from industry in 2014) and the American College of Cardiology (which she says received 38 percent of its revenue from industry in 2012).

In her investigation, Teicholz also examined the industry ties of specific members of the advisory committee, finding that they received support from groups like the California Walnut Commission, the International Tree Nut Council, Unilever, and Lluminari, a health media company that works with General Mills, PepsiCo, and Stonyfield Farm. “While there is no evidence that these potential conflicts of interest influenced the committee members, the [2015 dietary guidelines] report recommends a high consumption of vegetable oils and nuts,” Teicholz writes, while noting that most scientists in the field of nutrition receive some support from industry due to a shortage of public research funding.

Teicholz, author of The Big Fat Surprise, a book about the politics behind dietary fat recommendations, takes particular issue with the advisory committee’s push to restrict saturated fats, which it describes as a form of “empty calories.” She writes, “Unlike sugar, saturated fats are mostly consumed as an inherent part of foods such as eggs, meat, and dairy, which together contain nearly all the vitamins and minerals needed for good health.” She says the committee also did not sufficiently consider studies showing that low-carbohydrate diets are effective for promoting weight loss and improving heart disease risk factors.

Barbara Millen, the chair of the advisory committee, rejects allegations that the committee’s dietary recommendations are not supported by science. “The evidence base has never been stronger to guide solutions,” she was quoted as saying in the BMJ. “You don’t simply answer these questions on the basis of the NEL [Nutrition Evidence Library]. Where we didn’t feel we needed to, we didn’t do them. On topics where there were existing comprehensive guidelines, we didn’t do them.”

Millen defended the recommendations on saturated fat and said there had been insufficient evidence to consider low-carbohydrate diets, while adding that committee members were vetted by counsel to the federal government. But Teicholz isn’t convinced: “It may be time to ask our authorities to convene an unbiased and balanced panel of scientists to undertake a comprehensive review, in order to ensure that selection of the dietary guidelines committee becomes more transparent, with better disclosure of the conflicts of interest, and that the most rigorous scientific evidence is reliably used to produce the best possible nutrition policy,” she writes.

Update: The US Department of Health and Human Services has issued a statement about the BMJ article: “The British Medical Journal’s decision to publish this article is unfortunate given the prevalence of factual errors. HHS and USDA required the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee to conduct a rigorous, systematic and transparent review of the current body of nutrition science. Following an 19-month open process, documented for the public on DietaryGuidelines.gov, the external expert committee submitted its report to the Secretaries of HHS and USDA. HHS and USDA are considering the Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, along with comments from the public and input from federal agencies, as we develop the 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans to be released later this year.”