danny4stockphoto/Getty Images

With its year-round sunshine and vast tracts of fertile land, California is one of the jewels of US food production, providing a third of the nation’s vegetables and two-thirds of our fruits and nuts. As the climate warms, can we continue to take this $50.5 billion bounty for granted?

That’s the question posed by a team of University of California researchers in an eye-opening new paper published in the journal Agronomy, in which they digest recent research to “document the most current understanding on California’s climate change trends in terms of temperature, precipitation, snowpack, and extreme events such as heat waves, drought, and flooding, and their relative impacts” on the state’s agriculture.

They address these topics one by one, and the results are hardly comforting to US eaters.

For one thing, the scientists found, a temperature change of just a few degrees is “closely related to yield reductions” in some of the most cherished California crops: almonds, wine grapes, strawberries, walnuts, freestone peaches, and cherries. Avocado production could plummet by the middle of the century. Because of fewer winter chill hours, by the end of the century, the paper suggests, only 10 percent of the Central Valley will remain viable to grow fruits like apricots, kiwis, peaches, and nectarines.

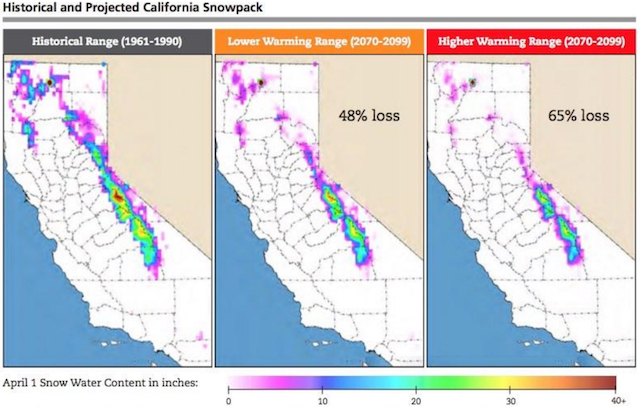

Then there’s the Sierra Nevada snowpack, the hoard of frozen water that gathers in the mountains on California’s eastern fringe over winter, before melting in the spring and irrigating farmland in the Central Valley, the state’s most productive farming region. California’s devastating recent drought (2012-2016) was largely driven by paltry winter mountain snows, which provide “almost 80 percent of the state’s precipitation in an average year,” the report notes.

And those dry times may already be back. As I reported in early February, a winter had left the snowpack at just 24 percent of its long-term average for the time of year. This past weekend, a big snowstorm raised it to 37 percent of average—still not great. Such levels may soon be considered the new normal. California’s snowpack has already “reduced considerably” in recent decades and is “projected to shrink further in the future climate,” the authors report.

Under an optimistic scenario, the snowpack is projected to be 48 percent lower in coming decades than it was in the 1961-1990 period. Under a more dire but realistic scenario, the pack will undergo a 65 percent loss.

Of course, when Central Valley farmers lack access to irrigation water that comes from melted snow, they revert to pumping it from underground aquifers. As we learned in the last drought, such massive withdrawals of a finite resource cannot go on long without causing severe problems, including dry wells, infrastructure-destroying land subsidence, and soil that’s too salty to grow most crops.

On top of the shrinking snowpack, the authors also note that “daytime and nighttime heat waves are expected to become more frequent and intense.” And as temperatures rise, the “impact of pests, diseases, and weeds is increasing substantially, with their altered growth cycles possibly becoming concentrated and impacting crop harvests,” they note.

In short, California’s climate has already “changed significantly” since the first half of the 20th century, when the state emerged as a linchpin of our food system. And “this change can be expected to continue in the future.” As I put it in a 2015 New York Times piece, the time has probably come to de-Californify the nation’s produce supply—that is, increase fruit and vegetable production in less water-stressed areas.