Supporters celebrate as they await the victory speech of Mike Braun, who defeated a Democratic incumbent in a race to represent Indiana in the US Senate, Nov. 6, 2018. Darron Cummings/Associated Press

In Tuesday’s midterm elections, President Donald Trump and his Republican Party largely tightened their grip over farm country, with the GOP winning most key races—with a few notable exceptions.

As the election drew near, the president doubled down on two positions that could have soured his relationship with the large-scale farmers who produce most of the nation’s food. He continued his trade war with China, prompting the country to slash its typically massive purchases of US-grown soybeans, pork, almonds, and sorghum.

And he escalated his campaign to demonize immigrants from Mexico and Central America, even though nearly three-quarters of US farm workers were born in that region, according to the latest data from the National Agricultural Workers Survey. Partly as a result of stepped-up border enforcement and immigration raids, one in three farmers report that the “difficulty of finding enough workers is making it harder to operate their farms and ranches and hindering their ability to expand,” according to a nationwide poll by the trade journal Agri-Pulse, released Nov. 7.

None of this mattered much on Tuesday. In California’s agriculture-dominated San Joaquin Valley, the globe’s epicenter of almond production, at least two Republican House members—Rep. Devin Nunes and Rep. David Valadao—survived spirited challenges from Democratic opponents who ran on promises to rein in Trump on trade and immigration. A third, Rep. Jeff Denham, held a narrow lead over his opponent, Josh Harder, as of Wednesday afternoon, but the race hadn’t been called yet.* (Here’s my October piece from the ground trying to make sense of that region’s tangled politics.)

In the soybean-heavy Midwestern states of Missouri, Indiana, and North Dakota, Republicans snapped up three Senate seats from incumbent Democrats. Sen. Joe Donnelly (D-Indiana) lost by nearly eight percentage points to Mike Braun, a businessman tightly aligned with Trump. According to county data crunched by the rural-affairs website Daily Yonder, Donnelly had a sizable edge in major urban areas but lost by double digits in rural zones—suggesting that the trade war and farm-labor crunch did little to harm the GOP in Indiana farm country.

Similar trends—Democratic candidates doing well in cities but bombing in rural areas—also played out in Senate races in three other states with substantial farm sectors: Texas, Florida, and Tennessee, Daily Yonder found.

There were bright spots for Democrats, too. In the most soybean-dominated state of all, Iowa, the Democrats grabbed two House seats from Republicans, and came close to taking a third. Rep. Steve King (R-Iowa) has long displayed virulently anti-immigrant views and allied himself with white nationalists. These positions became an albatross after a neo-Nazi killed 11 people at Pittsburgh synagogue in late October, causing the eight-term Congressman to lose support within his own party. But King still squeaked by with just 50 percent of the vote—vs. typical 60-plus percent showings—and will now be the only Republican in Iowa’s four-member House contingent.

And the GOP continues to have a strong foothold in the state: Republican Kim Reynolds was elected governor by three percentage points, a position she was first appointed to in 2017, when her predecessor, Terry Branstad, was tapped by Trump to be US Ambassador to China. Neither of the state’s Republican senators, Chuck Grassley and Joni Ernst, faced re-election in 2018.

So what explains the GOP’s relative success in farm country, despite the trade war and the immigration crackdown? When I visited California’s San Joaquin Valley a couple of months ago, Joe Del Bosque, who farms export-dependent almonds and labor-intensive melons, tried to explain it to me.

Farmers “like to support incumbents, because they’ve been at it a while and we’ve seen their record,” he says. “We’d rather not change horses in the middle of the stream, because we know who we got. We have somebody who can actually do something.” He noted that his region’s (now-re-elected) House GOP incumbents had proven they have the ear of the Trump Administration by drawing visits from cabinet members like USDA secretary Sonny Perdue and Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke; he did not articulate exactly what these encounters had accomplished.

He also expressed the hope that Trump may yet make a good deal on immigration. As for trade, when we spoke, the president had just completed a preliminary agreement with Mexico to replace the North American Trade Agreement, which later became the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement when Canada signed on. Del Bosque pointed to the budding deal as evidence that Trump would ultimately triumph in his trade war, opening bigger-than-ever market access for his California’s almonds.

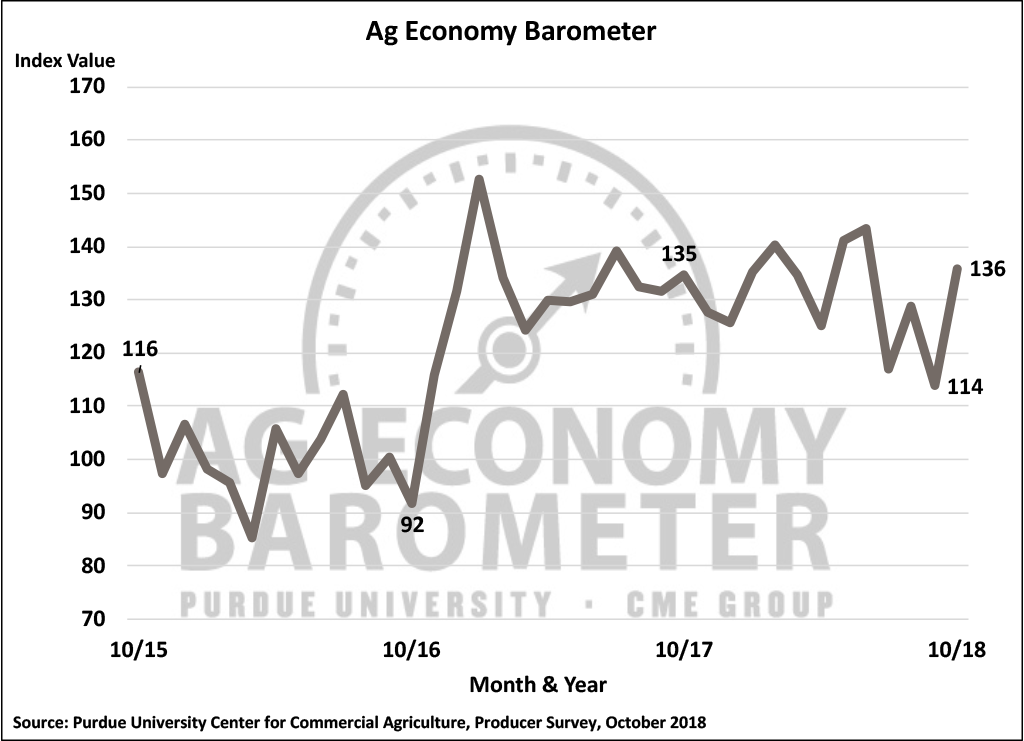

The USMCA has yet to be ratified, but other farmers are apparently impressed as well. The latest release from the Purdue University/CME Group Ag Economy Barometer, which surveys 400 farmers on their sense of the ag economy each month, found a sharp uptick in positive sentiment for October, just in time for the election.

Note that it surged with Trump’s election in 2016 and has seesawed ever since, but has remained above pre-election ’16 levels. More than 60 percent of the respondents told pollsters that the USMCA “somewhat” or “completely” relieved their farm income concerns over the next 12 months. It should be noted, however, that neither Mexico and Canada are huge buyers of US soybeans or almonds.

Update, November 14, 2018: Josh Harder ended up beating Jeff Denham, leading by 2.62 percent of the votes.