Traditionally, chicken musakhan was made around the olive oil pressing season in October or November to celebrate (and gauge the quality of) the freshly pressed oil.Jenny Zarins

On the international stage, discussion of the Occupied Palestinian Territory (as the United Nations calls Palestine) is often reduced to its long territorial conflict with Israel. As the occupation grinds on, Palestinians “live a harsh reality, but it’s not stopping them from living their life,” says chef Sami Tamimi, who was born and raised on Jerusalem’s Arab east side. “They still fall in love and get married and [have] kids—and they eat a lot and they love to share food.”

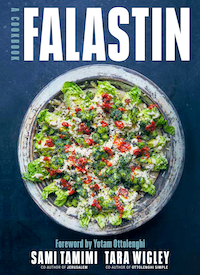

Tamimi started his culinary career in Palestine before moving to London as a young chef in 1997, where he met a fellow food-obsessed Jerusalem native, Yotam Ottolenghi, a Jewish Israeli. Together, Ottolenghi and Tamimi launched the celebrated Ottolenghi group of restaurants and cookbooks—including the 2012 jewel Jerusalem, a valentine to their shared, divided home city. (Tamimi remains executive chef and partner in the Ottolenghi enterprise.) Jerusalem largely avoided the bitter politics of Palestinian dispossession and revolt, focusing on the ancient city’s culinary glories. Tamimi’s new cookbook Falastin, co-written with fellow Ottolenghi stalwart Tara Wigley, is his effort to reclaim his homeland as more than a totem of intractable conflict—and reveal it as a place where people live full (though tightly constrained) lives and eat absolutely delicious food, while also portraying the “pretty grim picture” of the occupation.

In the latest episode of Bite, I caught up with Tamimi at a flat in Rome, where he is spending the summer.

Tamimi explained that Palestines are generally “obsessed” with food: “We sit down to breakfast and we’re [already] talking about what to cook for dinner.” And what breakfasts they have! In addition to more conventional fare like soft-cooked eggs served under a torrent of za’atar (the emblematic Palestinian herb mix) and chopped green onions, Falastin’s breakfast section includes “hummus two ways.”

Jenny Zarins

Tamimi’s hummus bears no relation to stuff you find packed in tubs at the supermarket. Silky smooth (from a five-minute food processor blitz) yet substantial (from a big addition of tahini), it’s served not as a dip, but rather as a luxurious pillow for savory toppings. The book offers two: feather-light beef meatballs and fried eggplant cubes, both lashed with fresh mint, toasted nuts, and olive oil. Not the sort of thing I’m going to be digging into often first thing on a Tuesday morning, but the combo did make for a glorious weekend brunch.

In Palestine, Tamimi explained, males are generally shut out of the family kitchen. “I always had a curiosity for cooking, since I was five years old,” he says. “I always snuck into the kitchen because I wanted to see what’s happening. I’d be pushed out, and then five minutes later, I’d be back.” His break came at the age of 16, when he asked his father for a bike. “He said to me, ‘just go out and work and get the money for the bike,'” Tamimi says. That led to a job as a dishwasher at a hotel restaurant, where a professional kitchen beckoned. Before long, he was waking up at 3:30 a.m. and riding his new bike to cook the breakfast shift, scrambling eggs for almost 200 people by hand.

While he didn’t learn to cook from the matriarchs of his home kitchen (his mom, who died when he was seven; and his aunts), Tamimi used his “excellent food memory” to recreate the dishes of his childhood, streamlining them to fit into busy lifestyles. In addition to the recipes, the book offers a beautifully written travelogue of Tamimi’s and Wigley’s trips through the fragmented occupied territories, with profiles of the people they met along the way, including Vivien Sansour, who runs the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library, which seeks to preserve ancient seed varieties and traditional farming practices—both under severe pressure from the occupation.

And Islam Abu Aouda, who lives with her family in a refugee camp in Bethlehem, offers cooking classes to visitors as part of the Noor Women’s Empowerment Group, a grassroots collective that raises funds for the area’s disabled kids, including her own eldest child. Aouda’s dream, beyond a stable place to live, is to visit the sea for the first time, Tamimi and Wigley report. She lives within three hours of the Israeli coastal town of Haifa, where Palestinians can’t easily go; “getting in the way is the paperwork needed, the visa often denied, the checkpoint lines so long and humiliating, the regular and real demands of her family,” the book explains. As for Gaza, the one chunk of Palestinian territory with Mediterranean coastline, getting there would require the same tangle of impediments, with an additional one: It’s under blockade, and anyone who visits risks getting trapped up there for months by Israeli forces, Tamimi tells me.

Tamimi and Wigley ultimately didn’t visit Gaza, opting not to risk getting held there. But they offer a blunt essay on the struggles of Gaza’s fisherpeople, whose boats are limited to within three miles of the coast, enforced by trigger-happy Israeli naval ships. As a result, they’re cut off from sardines, a one time staple. The restriction leaves them to “cull from the shallow waters close to the shore,” bringing in “small and young fish that if, left alone, would ensure their future prosperity,” the authors write. Fishing once provided a stable income for more than 30,000 Gazans and a robust source of high quality food for the region. Now, “a day at the sea can barely provide enough to feed a family, let alone take to market to sell.”

The Gaza essay’s opening sentence serves as a thesis statement for the whole book: “Writing Falastin, we’ve tried to strike a balance between telling it like it is in Palestine (which is not, clearly, always great), and conveying the upbeat spirit and ambition of the people we’ve met (which is, generally, always great).” That balancing act, achieved through deft storytelling and glorious recipes, has made Falastin the perfect guide as I cook my way through our national moment of grinding pandemic and political rot.

In the interview, Tamimi and I discuss the addictive, fiery-hot and and enlivening condiment shatta; and his take on Palestine’s national dish, chicken musakhan, a staple of his childhood. Here are the recipes.

Both recipes below reprinted with permission from Falastin: A Cookbook by Sami Tamimi and Tara Wigley, copyright © 2020. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

Chicken musakhan

Serves four

Musakhan is the hugely popular national dish of Palestine. Growing up, Sami ate it once a week, pulling a piece of chicken and sandwiching it between a piece of pita or flatbread. It’s a dish to eat with your hands and with your friends, served from one pot or plate, for everyone to then tear at some of the bread and spoon on the chicken and topping for themselves.

Traditionally, musakhan was made around the olive oil pressing season in October or November to celebrate (and gauge the quality of) the freshly pressed oil. The taboon bread would be cooked in a hot taboon oven lined with smooth round stones, to create small craters in the bread in which the meat juices, onion, and olive oil all happily pool. Musakhan is cooked year-round, nowadays, layered with store-bought taboon or pita bread, and is a dish to suit all occasions—easy and comforting enough to be the perfect weeknight supper as it is, but also special enough to stand alongside other dishes at a feast.

Playing around: The chicken can be replaced with thick slices of roasted eggplant or chunky cauliflower florets, if you like (or a mixture of both), for a vegetarian alternative. If you do this, toss the slices or florets in the oil and spices, as you do the chicken, and roast at 425°F for about 25 minutes for the cauliflower and about 35 minutes for the eggplant.

1 chicken (about 3¾ lb/1.7kg), cut into 4 pieces (3 lb/1.4kg), or 2 lb 2 oz/1kg chicken breasts with the wing-tips left on (between 4 and 6, depending on size), skin on, if you prefer

½ cup/120ml olive oil, plus 2 or 3 tbsp

1 tbsp ground cumin

3 tbsp sumac

½ tsp ground cinnamon

½ tsp ground allspice

Salt and black pepper

¼ cup/30g pine nuts

3 large red onions, thinly sliced ⅛ inch/3mm thick (mounded 4 cups/500g)

4 taboon breads (see headnote), or any flatbread (such as Arabic flatbread or naan bread; ¾ lb/330g)

¼ cup/5g parsley leaves, roughly chopped

1¼ cups/300g Greek yogurt

1 lemon, cut into wedges

Preheat the oven to 425°F. Line a rimmed baking sheet with parchment paper, and line a bowl with paper towels.

Place the chicken in a large mixing bowl with 2 tbsp of oil, 1 tsp of cumin, 1½ tsp of sumac, the cinnamon, allspice, 1 tsp of salt, and a good grind of black pepper. Mix well to combine, then spread out on the prepared baking sheet. Roast until the chicken is cooked through. This will take about 30 minutes if starting with breasts, and up to 45 minutes if starting with the whole chicken, quartered. Remove from the oven and set aside. Don’t discard any juices that have collected in the pan.

Meanwhile, put 2 tbsp of oil into a large sauté pan, about 10 inches/25cm, and place over medium heat. Add the pine nuts and cook for 2–3 minutes, stirring constantly, until the nuts are golden brown. Transfer to the prepared bowl (leaving the oil behind in the pan) and set aside. Add the remaining ¼ cup/60ml of oil to the pan, along with the onions and ¾ tsp of salt. Return to medium heat for about 15 minutes, stirring from time to time, until the onions are completely soft and pale golden but not caramelized. Add 2 tbsp of sumac, the remaining 2 tsp of cumin, and a grind of black pepper and mix well, until the onions are completely coated. Remove from the heat and set aside.

When ready to assemble the dish, preheat the broiler and slice or tear the bread into fourths or sixths. Place under the broiler for 2–3 minutes, to crisp up, then arrange on a large platter. Top the bread with half the onions, followed by all the chicken and any chicken juices left in the pan. Either keep each piece of chicken as it is or roughly shred it, into two or three large chunks, as you plate up. Spoon the remaining onions over the top and sprinkle with the pine nuts, parsley, remaining 1½ tsp of sumac, and a final drizzle of olive oil. Serve at once, with the yogurt and lemon wedges alongside.

Shatta (red or green)

Makes 1 medium jar

Sami knew that he had a true partner in culinary crime in Tara when he spotted a jar of this in her bike basket one day. “I don’t go anywhere without some,” Tara said, as casually as if talking about her house keys. Shatta(ra!) is on every Palestinian table, cutting through rich foods or pepping up others. Eggs, fish, meat, vegetables—they all love it. Our recommendation is to keep a jar in your fridge at all times. Or your bike basket, if so inclined.

Equipment note: As with anything being left to ferment, the jar you put your chiles into needs to be properly sterilized (instructions below).

9 oz/250g red or green chiles (with seeds), stems trimmed, very thinly sliced

1 tbsp salt

3 tbsp cider vinegar

1 tbsp lemon juice

Olive oil, to cover

Place the chiles and salt in a medium sterilized jar and mix well. Seal the jar and store in the fridge for 3 days. On the third day, drain the chiles, transfer them to a food processor, and blitz; you can either blitz well to form a fine paste or roughly blitz so that some texture remains. Add the vinegar and lemon juice, mix to combine, then return the mixture to the same jar. Pour enough olive oil on top to cover, and keep in the fridge for up to 6 months. The oil will firm up and separate from the chiles once it’s in the fridge, so just give it a good stir, for everything to combine, before using.

*Sterilizing jars is a necessity when preserving foods; makdous, for example, or shatta. It ensures that all bacteria and yeasts are removed from a jar so that the food remains fresh. There are various ways to sterilize a glass jar; including a water bath, where the jars go into water, with their lids added separately, the water is brought to a boil, and then the jars are “cooked” for 10 minutes, or filling the jars with just-boiled water and then rinsing and drying with a clean dish towel. We tend to just put ours into the dishwasher, though, and run it as a normal wash—it’s a simple solution that works very well.