Paul Bersebach/MediaNews Group/Orange County Register via Getty Images

As the debate over raising the minimum wage heats up, there has been renewed attention on the subminimum wage that restaurant servers make in many states, also called the tipped minimum wage. House Democrats’ proposed Raise the Wage Act would increase the minimum wage to $15 an hour over the course of five years, and would also phase out the subminimum wage in the states where it still exists.

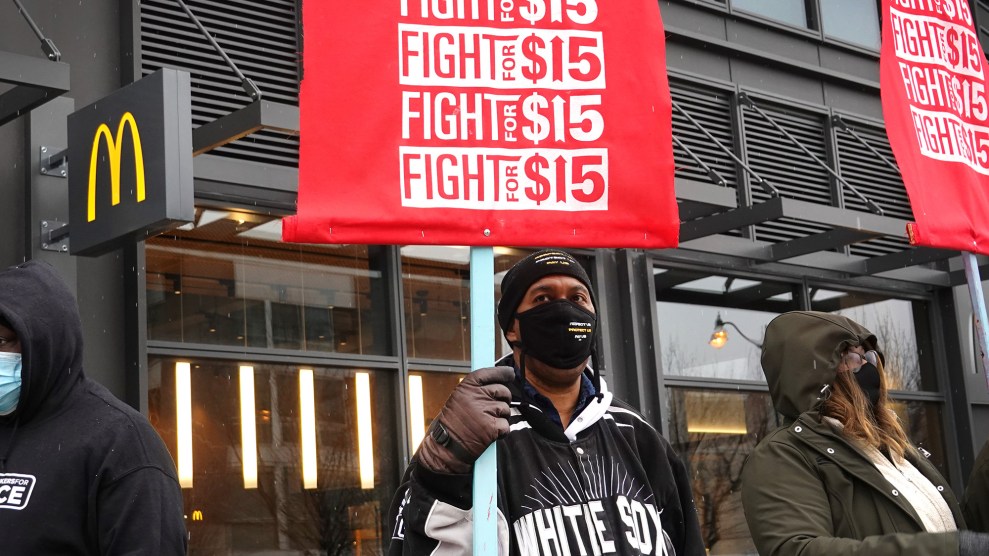

Not everyone’s happy about either of these ideas: The National Restaurant Association, a trade group that represents large chain restaurants like McDonald’s and Darden Restaurants, argued in a recent op-ed that “wage hikes hurt restaurants” that are “stretched to the brink financially,” and the proposal to strike the tipped minimum wage comes at the wrong time for struggling servers.

Will ditching the subminimum wage actually hurt restaurants? A new report by One Fair Wage, a nonprofit advocacy group for restaurant workers, shows some evidence to the contrary.

The report, which relied on an analysis by a team of Harvard researchers, found that in states where the subminimum wage has already been eliminated—meaning tipped workers are paid the minimum wage with tips on top—have, on average, experienced almost the same rate of decline in hotels, restaurants, and other hospitality businesses as states that continue to have the subminimum wage. The researchers’ analysis focused on January 2020 to January 2021.

For example, tipped workers in California earn $14 an hour, which is the same as minimum wage workers. In the past year, the state saw a 52 percent decline in leisure and hospitality businesses—the same rate as Maine, where tipped wages are set at $6.08, or half of the state’s minimum wage.

The report also found that states with the highest rates of decline in hospitality businesses—Michigan, New Mexico, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts—are all states with the subminimum wage.

As David Cooper, senior economic analyst at the Economic Policy Institute, notes in the report, minimum wage hikes result in stronger buying power to workers. In turn, hospitality businesses benefit from the extra purchases. “Tax breaks or deferrals, rent subsidies, expanded lending programs, and other business-oriented relief measures all help firms weather a downturn,” Cooper says, “but they’re not going to drive additional spending in the same way that a minimum wage hike does.”