The farm bill is one of the most important but least understood pieces of US legislation, and it’s overdue for renewal. But Congress couldn’t pass a new version in the fall, reflecting partisan dysfunction and also a contentious debate about what the bill ought to be—a debate that has become ensnared in the nation’s culture wars. Racial equity, food sovereignty, protections for workers, and meaningful action on climate change have broadened the bill’s traditional mandate of growing food and feeding hungry people. In this special series, a partnership with the Food and Environment Reporting Network, we’ll be exploring some of the urgent issues a new farm bill must address. Read the other stories in the series here.

The farm bill was once an example of bipartisan bonhomie in Washington. The recurring five-year legislation—a marriage of farm subsidies and nutrition assistance programs—gave both rural Republicans and urban Democrats in Congress strong incentives to support it, even if neither group was entirely satisfied. Pork helped, as it does. The bill has always relied on handouts to grease its wheels, like large milk subsidies that particularly benefited dairy farmers in states that happened to have powerful members on the Senate Agriculture Committee, or billions for an ethanol industry that likely wouldn’t exist without government help. The bill’s horse-trading quality, giant price tag, and broad mix of programs have always made it complicated to get across the finish line. Yet despite contentious fights and delays, final passage of some kind of omnibus compromise has rarely been in doubt.

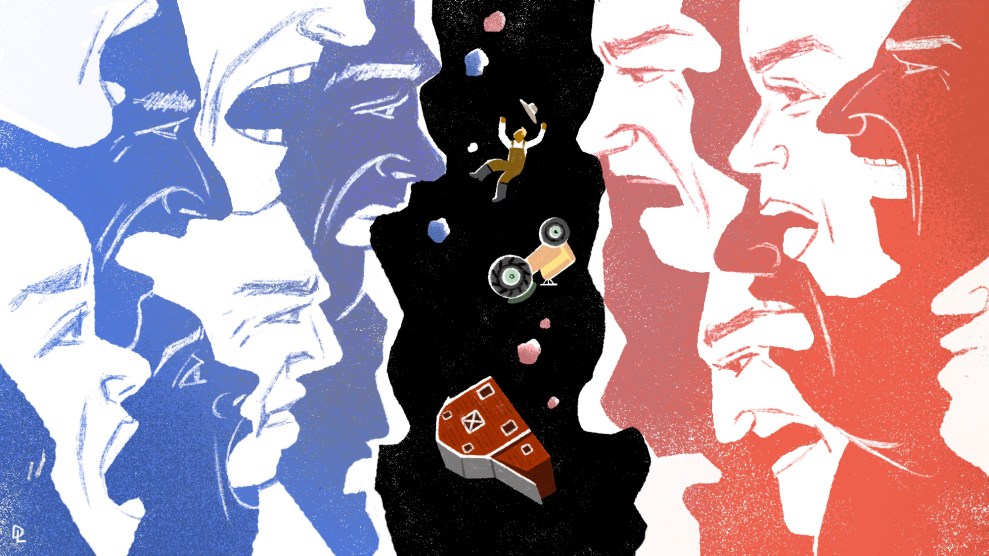

But that may be starting to change. Hyperpartisan combat is the rule of the day in Washington, and even old staples of bipartisan legislation like the farm bill are increasingly swirling into a doom loop where the two parties are incentivized to escalate fights and disincentivized to compromise. “This farm bill is not going to be about the policy, this farm bill is going to be about the politics,” said Rep. Kat Cammack (R-Fla.) in August. She estimated that 30 to 40 members of both parties had already decided that they wouldn’t support a farm bill before a bill was introduced. Earlier in 2023, the right-wing House Freedom Caucus instructed its new members to use conflicts around the farm bill “as leverage points to enact a conservative policy agenda.” Anticipating the assault from the right, Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) said that Democrats should approach the farm bill “on the offensive and drawing lines in the sand.”

That posture kept Congress from making progress on new legislation after the current farm bill expired last September. So they kicked the can to September 30 of this year. Will the process get easier before then? Unlikely, but Congress famously requires the pressure of a deadline to get its work done. But in case you hadn’t heard, there will be an election this fall—an extremely divisive, hotly partisan election—right when Congress will face its new deadline on the farm bill. That’s not a recipe for bipartisan bonhomie.

This is a high-stakes problem. If the bill is allowed to expire without another extension or new bill, its commodity programs will revert back to “permanent law”—standards set by the farm bills in 1938 and 1949. That would create an economic disaster. The government would begin buying products off the market, causing prices of essentials like milk to skyrocket. And although SNAP benefits (food stamps) and federal crop insurance are permanently funded, some of the farm bill’s smaller programs would run out of money and begin to lose the legal authority to function. Programs to help organic farmers compete or to help seniors afford locally grown produce would be some of the first to be affected.

Delays have consequences, too. It costs more to farm than it did when the last farm bill was passed in 2018, and the reference prices that determine when farmers get financial assistance for particular crops need updating. A year’s delay in cost updates can make a big difference in an industry where a drought, storm, or early fall freeze can dramatically alter a farmer’s economic picture. That’s the reason the farm bill is reconsidered every five years—to keep the Depression-era law up to date with the needs of the day.

And while the worst case scenario of missing the deadline and reverting back to permanent law seems unlikely, nothing is certain in this Congress. It is, after all, the same group that spent three weeks last fall aimlessly playing musical chairs with the Speaker of the House and was one of the least productive Congresses in recent history.

So why are we here? Why can’t Congress get this done?

The answer is the political doom loop, in which polarization leads to dysfunction, leading to more polarization and more dysfunction. More than 90 percent of congressional districts were uncompetitive in the last election, meaning that the overwhelming majority of representatives have districts that are safe for their party. Gerrymandering makes this worse, but the core problem is that Republicans and Democrats increasingly live in different places. The boundary lines in the farm bill fight make this clear: Democrats increasingly represent largely urban, very liberal districts; Republicans largely rural, very conservative ones. Representatives who choose legislative combat over compromise are representing the hyper-partisan demands of their most loyal and active voters. In this political environment, it can be strategically savvy to use everything you can get your hands on as a political weapon against your opponents.

Jim Jordan, the Republican congressman from Ohio who came within a handful votes of being elected Speaker last year, is perhaps the perfect exemplar of the farm-bill-as-weapon strategy. In a decade and a half in Congress, Jordan has never voted for a farm bill, instead using the opportunity to show off his proud unwillingness to compromise with Democrats. When Jordan first came to office in 2007, that approach was not so common; former Republican House Speaker John Boehner famously referred to Jordan as a “legislative terrorist” due to this kind of posturing. Seventeen years later, Jordan’s approach is widespread among House Republicans, the overwhelming majority of whom voted to overturn the 2020 election, and Jordan himself was nearly made Speaker.

Members of Congress who want to find something to oppose in the farm bill have plenty of options. First is the bill’s main feature: the nutrition assistance programs, such as SNAP, which takes up about 80 percent of the bill’s funding. Republicans have long wanted to separate out food stamp funding from the farm bill, and in its 2023 budget proposal, the Republican Study Committee, the largest conservative caucus in the House, suggested doing just that. Separating SNAP from the rest of the bill would allow Republicans to slash its funding and include more work requirements for Americans who receive food stamps. Democrats have indicated that they won’t budge.

A second sticking point involves the reference prices. If the market price of a particular crop falls below the reference price, government assistance kicks in so that farmers get at least something for their yield. But many farmers argue that the reference prices are so low that they barely make a difference. (One farmer recently told Iowa Public Radio: “It’s not a safety net, it’s a safety asphalt.”) Increasing reference prices, however, would mean either increasing the price tag of the already expensive farm bill or reallocating money from some other part of the bill. (A 10 percent increase in reference prices could cost around $20 billion). And big price tags are hard to swallow for members who don’t want to be labeled “big spenders.”

Then comes President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act. The law, passed by Democrats in a partisan budget reconciliation process, set aside $20 billion for “climate smart” agriculture practices. Republicans want to fold this funding into the farm bill and reallocate some of the money for conservation purposes separate from the greenhouse gas-reducing priorities of the IRA. Democrats want to keep it solely focused on climate if it is built into the farm bill.

These kinds of fights aren’t new. What is new is that a growing number of representatives have a political incentive to prefer an unresolved fight over a compromise deal. In today’s political environment, walking away from a problem can make better strategic sense than working to find a solution. That’s especially true during a viciously partisan election like the one we’ll face this fall.

This is a consequence of the larger two-party doom loop of escalating partisan warfare poisoning every other area of American politics today. To truly fix the problem at its core would require significant structural reform, like changing our congressional district system to elect multiple members in each district in proportion to their party’s amount of support. Reforms like proportional representation would help make space for the more fluid coalitions that once facilitated compromise legislation on Capitol Hill.

But in the immediate term, we are left to hope that level heads prevail among the sitting members of this Congress. If a new bill gets passed, it will likely be driven more by the Senate, which has longer terms of office and slightly more wiggle room to negotiate between the two sides. Or maybe the 2024 presidential race will be so outlandishly toxic that it will take attention off everything else, giving Congress some breathing room to make deals.

Whatever happens, the doom loop that got us here is not going to resolve on its own. If a new farm bill manages to squeak through this fall, as it must, the trends of recent years suggest that it will only be harder next time. Politicians will continue to turn plowshares for farming into swords for partisan fighting. And without changing the underlying problems in our politics, we’ll only be further eroding our own democratic soil.

Correction, February 1: This article has been updated to make clear that Inflation Reduction Act funding is not already in the farm bill.