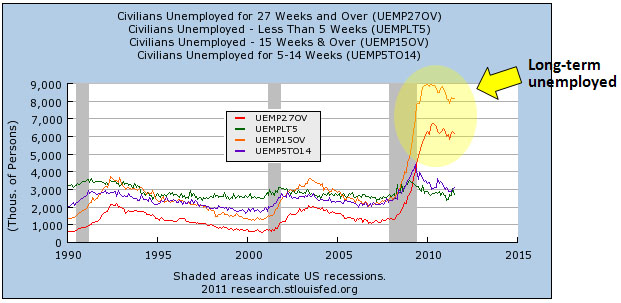

When an economy goes into recession, an obvious response should be lower wages for workers. However, there’s lots of empirical evidence that employers are reluctant to lower the wages of their workers, and it’s easy to understand this on a social basis: it’s bad for morale, it makes managers feel like dicks, etc. etc. Even in a very bad recession like the one we just went through, most employers weren’t willing to go any further than making some modest cuts in benefits (higher copays for health insurance, lower contributions to retirement funds, and so forth).

But what about the unemployed? Why is it that they don’t eventually lower their wage expectations enough to make themselves more employable? Tyler Cowen runs through a few of the arguments on this score and finds them all unsatisfactory. He concludes that neo-Keynesian models are badly lacking:

Often when this topic comes up I feel I am playing a game of whack-a-mole. Most of all, I am struck by how little attention people pay to their own sticky nominal wage hypotheses. If that were the problem, and if unemployment were today’s biggest issue (a totally plausible claim), you might expect people to blog the microfoundations of nominal wage stickiness very, very often. You might expect ethnography. Micro-level data. Lots of juicy anecdotes and journalistic features, not just on the unemployed but on the stickiness itself. Perhaps some micro-level advice. Dozens, no hundreds of blog posts on the all-important microfoundations of the #1 social problem of our time.

But no, there’s not much of those to be seen. At some level it is understood, if only implicitly, that the sticky nominal wage theory is an embarrassment — when it comes to the unemployed across the longer run (but not the employed). It doesn’t get too close a look.

What else? Few people want to come out and utter the possibility: “They’re just too stupid and too stubborn to lower their wage demands.” Mood affiliation reigns, and the prevailing mood is to express sympathy with the unemployed. In fact that sentence is not my view, but it actually makes somewhat more sense than most of what is listed above. A lot of people don’t like hypotheses which suggest the unemployed are not victims of the system, so it doesn’t get much of a hearing.

I am not an economist (IANAE for short), and I don’t understand the importantance of sticky wages to models of long-term unemployment. But I guess I’m unclear about how important this really is outside of the academic modeling universe. Tyler says he doesn’t believe the folk wisdom that people are just too stubborn to lower their wage demands, and I don’t either. I simply know far too many examples of people who are extremely willing to accept much lower wages than they used to make. Maybe not right away, but within a few months or a year at the outside, virtually everyone is willing to accept a pretty sizeable pay cut.

One problem with this, on a purely social (i.e., non-economic modeling) basis is that employers have always been leery of hiring people at reduced wages. They’re afraid you’ll be bored with a less challenging job. They’re afraid you’ll be unhappy over your salary and bring a bad attitude to work. They’re afraid you’re just taking something out of desperation and will jump ship the minute something better comes along. They’re afraid that your willingness to accept less is a sign that you know you’re unemployable because you’re a lousy worker.

But does any of this matter? Tyler suggests a different explanation for long-term unemployment that has nothing to do with wage demands: “I think, by the way, that excess capacity theories are one of the most plausible attempts to explain continuing unemployment….The firm doesn’t want to produce any more output, so the worker’s wage demands don’t matter so much. This will have real import for the analysis of monetary and fiscal policy, so the microfoundations really matter here.”

This is where I get confused. In the real world of op-eds and columns and blog posts, as opposed to academic papers stuffed with Greek letters, isn’t this exactly what nearly everyone is saying? It’s not that workers aren’t willing to accept less, and it’s not that workers have suddenly become useless in our brave new high tech society. The problem is that we’ve gone through a financial collapse, households are overleveraged, and this has cratered demand for goods and services. With demand low, firms have no expectation that their business is likely to expand, so they aren’t hiring unemployed workers at any wage. Add to that the social issues I mentioned above, and the long-term unemployed are screwed.

Obviously I’m skipping over the deep microeconomic modeling issues here, which are legitimately important to economists, but how does that really affect real-world monetary and fiscal policy? We live in a world that’s got too much debt overhang, and outside of the weirdo fringe, I’ve mostly heard pretty similar approaches to dealing with that from both left and right. So I guess I’m a little unclear about how and whether sticky wages really matter much.