Did Paul Ryan lie repeatedly in his acceptance speech last Wednesday, as countless fact-checking articles later claimed? Stephen Hayes thinks it’s an unfair charge. “Here’s the funny thing about most of these articles,” he says in the Weekly Standard today. “They fail to cite a single fact that Ryan misstated or lie that  he told. In most cases, the self-described fact-checks are little more than complaints that Ryan failed to provide context for his criticism of Barack Obama.”

he told. In most cases, the self-described fact-checks are little more than complaints that Ryan failed to provide context for his criticism of Barack Obama.”

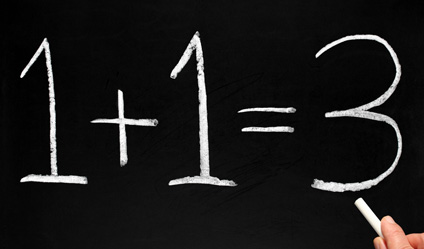

He’s right. There are two big problems with getting obsessed about “lies.” The first is that it’s usually too hard to prove. You have to show not only that something is unquestionably factually wrong, but that the speaker knew it was wrong. That’s seldom possible. The second problem is that it’s too narrow. Politicians try to mislead voters all the time, and only occasionally do they do this with flat-out lies. Bottom line: if you focus only on actual lies, you miss too much. But if you try to turn everything into a lie, you sound like a hack.

A better approach is to focus instead on attempts to mislead. But how do you judge that? A few years ago I developed a three-part test that I use to check my immediate emotional reaction to things politicians say. I’ve found it pretty useful in practice, though it’s not perfect and it doesn’t apply to every kind of slippery statement. Here it is:

- What was the speaker trying to imply? This is necessarily a judgment call, but it’s what gets us away from “lying” and instead focuses our attention on how badly a speaker is trying to mislead us.

- What would it take to state things accurately? This is the most important part of the exercise. Without getting deep in the weeds (nobody expects politicians to speak in white paper-ese), what would it take to restate things reasonably accurately?

- How much would accuracy damage the speaker’s point? Obviously, if accuracy dents the speaker’s point only a bit, not much harm has been done. If it demolishes the speaker’s point completely, it’s as bad as an actual lie.

Here’s an example from Ryan’s speech, where he talked about the $716 billion “funneled out of Medicare by President Obama”:

- He’s implying that Obama reduced Medicare spending and this will hurt Medicare beneficiaries, something that Republicans oppose.

- A more defensible version might be something like this: “Obama has reduced payments to hospitals and private Medicare plans. This will lead to less service, lower quality, and fewer plan choices for seniors. Until a few weeks ago, I thought this was a good idea and proposed the same cuts in my budget, which was supported by 95% of the Republican caucus in the House.”

- The first two sentences don’t damage Ryan’s point much at all. The third sentence is a major change that turns it completely on its head. On a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 is reserved for flat-out lies, this is about a 9. There’s obviously a huge attempt to mislead here.

Here’s another one. Ryan talked about Obama’s 2008 visit to a GM plant in Janesville, where he told the workers, “I believe that if our government is there to support you … this plant will be here for another hundred years.” On Wednesday Ryan said: “Well, as it turned out, that plant didn’t last another year. It is locked up and empty to this day. And that’s how it is in so many towns today, where the recovery that was promised is nowhere in sight.”

- He’s implying that the plant closed on Obama’s watch and that lots of other plants remain shuttered because the economy has remained weak.

- A more accurate version would go something like this: “That plant closed before Obama took office, and none of his bailouts or stimulus bills were able to bring it back to life. And that’s how it is in so many towns today, where the recovery that was promised is nowhere in sight.”

- This is a small change, and frankly, it doesn’t really change the emotional resonance of the sentence much. It’s maybe a 2.

I chose these two examples for a reason. The first one, on examination, was worse than I thought. Obama did cut planned Medicare spending by $716 billion, so at first glance an accurate rephrasing didn’t change Ryan’s point much. But when I remembered that Ryan and the entire Republican caucus had supported those cuts just a few months ago, it was obvious that this was a major-league whopper — and there’s simply no way to restate it without changing its impact completely. The attempt to mislead is enormous.

Conversely, the second example annoyed me a lot when I first heard it, but when I went through the exercise of writing a more accurate version, I realized that it didn’t really change things much. The restated version has much the same impact as the original. There’s an attempt to mislead here, but for most listeners it’s fairly subtle.

It’s Step 2 of this test that’s key. You have to rewrite the offending statement to be defensibly accurate. Keep in mind that this doesn’t mean rewriting conservative attacks to include every possible liberal talking point. This is a presidential campaign, not a graduate seminar. You need to do the absolute minimum it would take to make the statement tolerably defensible.

Needless to say, this doesn’t work for everything. In Romney’s infamous welfare ad, for example, he says that Obama is “dropping work requirements” and “Under Obama’s plan, you wouldn’t have to work and wouldn’t have to train for a job. They just send you your welfare check.” This actually is a flat-out lie, not merely an attempt to mislead. Beyond that, though, the real dirty work of the ad is the way it pushes obvious racial hot buttons, and that’s simply not something you can judge on a scale of truthfulness vs. deceit.

Still, for many things, this test is useful. What’s the minimum change it would take to keep the offending statement from being actively misleading? Once you’ve made the change, how much does it really change the emotional resonance of the statement? If you do an honest job of this, you might surprise yourself now and again.