If banning leaded gasoline—and thus reducing childhood exposure to airborne lead—leads to less violent crime when all those children grow up, shouldn’t it also lead to a smaller prison population? Yes it should. But there are problems. First, prison sentences tend to be long, so even when the number of new offenders began to decline in the 90s, we were still adding to a prison population that included lots of offenders from the 80s who weren’t going to be released anytime soon. So the prison population continued to grow. Second, the great crime wave of the 70s and 80s spawned an enormous public policy reaction. Courts got tougher, sentences got longer, and things like three-strikes laws became commonplace. So even as violent crime rates declined, more suspects were caught and convicted, and a larger percentage of them were given long prison sentences.

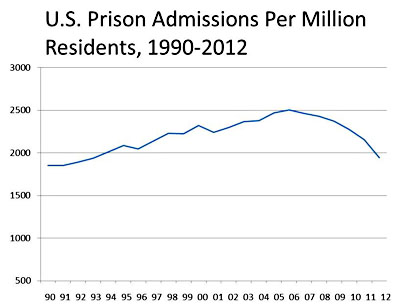

But eventually incarceration rates were bound to catch up anyway. After all, there’s a limit to how many new cops you can put on the streets and how much tougher you can make sentencing policy. So have they? Unfortunately, total prison population tells us more about policies and crime rates in the past, when today’s prisoners were first  incarcerated, than it does about today. So Keith Humphreys decided instead to take a look at new prison admissions. He was pleased with what he found:

incarcerated, than it does about today. So Keith Humphreys decided instead to take a look at new prison admissions. He was pleased with what he found:

I was startled and encouraged to see that under current policies, we are at a two decade-year low in the prison admission rate. To provide historical perspective, peg the change to Presidential terms: When President Obama was elected, the rate of prison admission was just 3% below its 2006 level, which was very probably the highest it has ever been in U.S. history. But by the end of Obama’s first term, it had dropped to a level not seen since President Clinton’s first year in office.

As dramatic as these changes are, the prison population would be declining even faster if we fully accepted the logical consequence of the lead-crime hypothesis: not just that violent crime rates have plummeted over the past two decades, but that they’re likely to stay low. The problem is that our sentencing and incarceration policies are a vestige of an era when violent crime was rampant and only a harsh and iron-fisted response seemed to have any chance of stopping it. But we no longer need those policies. We could return to a less severe approach without endangering public safety if only we had the will to do it. America’s young simply aren’t as violent as they used to be.

Not convinced yet? Here’s some further data from Rick Nevin:

From 2002 to 2012, the incarceration rate fell 51% for men ages 18-19, 30% for men ages 20-24, and 21% for men ages 25-29….The prison population has fallen at a slower rate because steep incarceration declines for young men have been offset by rising incarceration for older adults. From 2007 to 2012, the incarceration rate increased by 21% for men ages 45-49 and surged 45% for men ages 50-64.

Incarceration rates are way down for men in their teens and 20s, who grew up in the relatively lead-free post-1990 environment. But for older men, who grew up before then, incarceration rates are actually up. Lead did its work on them long ago.