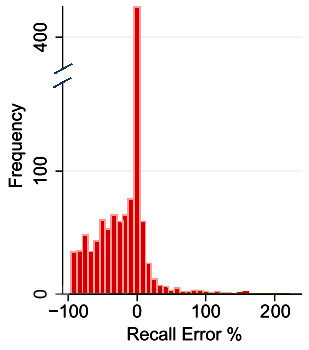

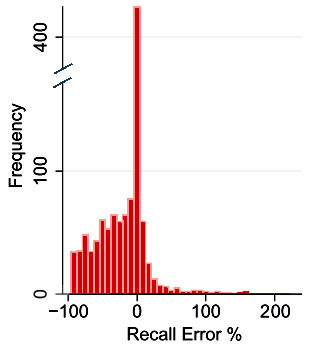

Over at Wonkblog, Christopher Ingraham points us to new research from Ireland suggesting that an awful lot of people don’t know how much they paid for their houses. I’ve adapted the main chart from the study on the right. As you can see, most people who get this wrong underestimate how much they paid—sometimes by gigantic amounts. Very few people overestimate how much they paid, and virtually no one overestimates by more than a quarter or so.

Over at Wonkblog, Christopher Ingraham points us to new research from Ireland suggesting that an awful lot of people don’t know how much they paid for their houses. I’ve adapted the main chart from the study on the right. As you can see, most people who get this wrong underestimate how much they paid—sometimes by gigantic amounts. Very few people overestimate how much they paid, and virtually no one overestimates by more than a quarter or so.

What accounts for this? As it happens, the authors are mostly concerned with how this poor recall affects estimates of the wealth effect—which I admit I didn’t really understand.1 Because of this focus, they don’t spend a lot of time speculating on the underlying causes. But they do mention that the older the loan, the less accurate people are; that younger people remember better than older people; and that errors are smaller among the well-educated.

But none of this explains why the bad recall is overwhelmingly on the low side. So here’s my guess: people lie. Or, more charitably, they’re in denial. They don’t want to admit to themselves or their friends how much they lost during the housing crash. Or, when prices are rising, they like to brag about how much they’ve made. Everyone else claims to have made a killing, so they slice a little bit off their buying price to make it seem like they made a killing too. No one wants to be a sucker, after all. Do this enough times, and eventually you come to believe it yourself.2

1The authors say that “An increasing number of micro based estimates of the housing wealth effect use the recall house price as an indicator of housing wealth.” So if recall prices are systematically lower than the actual prices paid, this would lead to estimates of the wealth effect that are too low.

That’s fine, and it’s a reasonable topic for a research paper. It’s important to know just how the wealth effect works. But why would anyone use the recall price for this in the first place? Shouldn’t wealth effect estimates be based on how much people think their houses are worth right now? Or on how much equity people think they have, which would actually be higher if they underestimate the original price of their house? I’m a little stumped by this.

2Here’s another guess: people tend to remember loan amounts more than the actual price of the house. If they put 10 percent down on a $300,000 house, the amount of the loan is $270,000, and that’s what they remember. I’m not sure I buy this, but it’s a possibility.