Late last fall, Dick Cheney began speaking of the “Salvador option” as a strategy for gaining a conclusive victory in the Iraq War. His comments, echoed by conservative pundits in the weeks that followed, recalled the time, in the early 1980s, when the maps and place-names beamed into American homes on the nightly news were not those of Fallujah or Baghdad, but of El Mozote and San Salvador.

Commentators who today invoke El Salvador hold it up as an example of the United States defeating an insurgency with minimal use of American personnel—by providing arms, training, and support to local counterinsurgents. It is unclear exactly what such a tactic would look like in Iraq, though one presumes it could mean anything from arming Shia militias to root out Sunni insurgents to the formation of Salvador-style death squads. In invoking El Salvador, though, the pundits say little about how the US government’s policy of propping up a right-wing military regime and its allied paramilitaries was experienced by the population on the ground. Nor do they acknowledge that the eventual folding, after a dozen years, of Salvador’s leftist FMLN guerillas owed as much to external political factors as to the efforts of the U.S.’s proxy forces. Indeed, that El Salvador can be held up as a successful case of American interventionism suggests how dim memories have become of what actually happened there.

In this context, the American release of Luis Mandoki’s Innocent Voices is especially welcome. Based on the life-story of Oscar Torres, who co-wrote the script with the Mexican-born Mandoki (heretofore best known in this country for Lifetimey weepers like Message in a Bottle and Angel Eyes), it takes place in 1980, at the outbreak of the Salvadoran civil war. The setting is the small village of Cuscatanzingo, where Torres, then 11 years old, lived with his mother and siblings. Unlike the Hollywood movies that portrayed these events as they were unfolding—movies such as Oliver Stone’s classic Salvador, which, Graham Greene-style, had jaded gringo journalists working out internal dramas amidst Third World bloodshed—Innocent Voices depicts the Salvadoran War from the point of view of the civilians who endured its greatest suffering.

Innocent Voices follows a year in the life of a waist-high protagonist named Chava (the extraordinary Carlos Padilla), based on Torres, as he and his community confront the ever-present threat of forced conscription—the Salvadoran Army’s policy being to press boys as young as 12 into service against the leftist guerrillas—and the steadily encroaching violence of the war.

Chava inhabits a world peopled mostly by schoolmates and female relatives, nearly all the surviving able-bodied men of Cuscatanzingo having departed either for military camps or the United States. The film’s action takes place entirely within this circumscribed world, and Mandoki gives us a dense and vivid depiction of life in a conflict zone. As Innocent Voices unfolds, we see how every one of the spaces in which the townspeople live their lives—the school, the church, the central square and their ramshackle homes, the bridge in between, the river below—are defiled by the war. Any illusion the characters may nurture of the normalcy of their lives is quickly broken the sight of menacing soldiers on patrol (often joined by shadowy American advisors), or the loud report of a nearby explosion. As Chava and his classmate Cristina Maria share their first chaste kiss one afternoon on a rooftop in town, they are pulled back to the degraded adult world around them by the cries of two women being seized and tossed in the back of a jeep by green-helmeted soldiers in the street below. Each day children play at war on gravel streets that become the setting for real gun battles each night, battles that awaken those same children from their dreams in tears, as bullets whiz through their open windows.

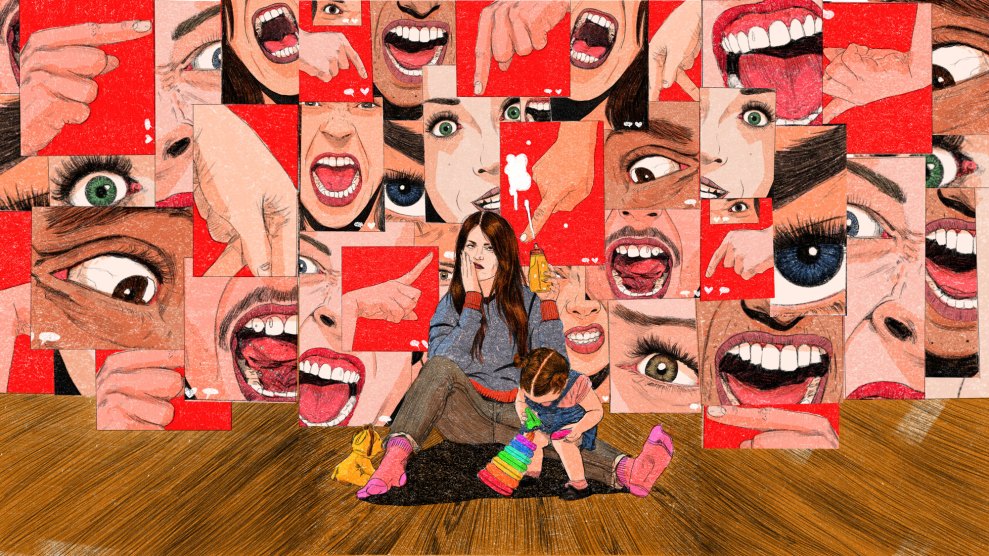

The victims of violence in Innocent Voices are, as the film’s title suggests, rarely the people bearing weapons. We see almost no shooting of actual soldiers or guerillas; instead, we see families separated, children brutalized, innocents lynched. The means of pacifying a popular insurgency here is not the killing of insurgents but rather the decimation and demoralization of the civilian population thought to sustain the insurgency—which is to say, the very people the counterinsurgents are nominally trying to win over. The idea is to kill not the bandits in the mountains but whomever it is easy to kill, stealing away sons, terrorizing families—all to convince people that, as long as their brothers and sisters and uncles are willing to fight, it is they who will suffer.

Were it not based in the life-experience of Torres, the sympathetic depiction of the guerillas would no doubt be cited as evidence of the film’s lefty agenda—and it will inevitably attract some such accusations. The truth, however, is that two decades later, the dynamics of the conflict on the ground in El Salvador are quite beyond debate: over the course of the war, some 1 million people were forced to flee the country; more than 75,000 civilians lost their lives, the vast majority at the hands of the military and right-wing death squads, forces either supported or tolerated by the United States.

Today, the focus of America’s foreign policy has shifted away from Central America and to the Middle East. On the surface, the Iraq conflict would seem to have little in common with the Salvadoran civil war. The geopolitical calculations are no longer those of the Cold War. And in this new war, it is the insurgents that have taken to killing civilians as a matter of strategy, leaving the Iraqi people in the dire position of risking death from one side if they deal with the Americans and from the other if they do not. As in El Salvador, though, the people suffering most are the civilians whose hearts and minds are supposedly at stake, but whose lives are treated as disposable—a situation that could likely only be made worse by further proxy militarization. For those seeking to know the true nature of the “Salvador option,” Innocent Voices could hardly have come at a better time.

Innocent Voices is now showing in select theaters.