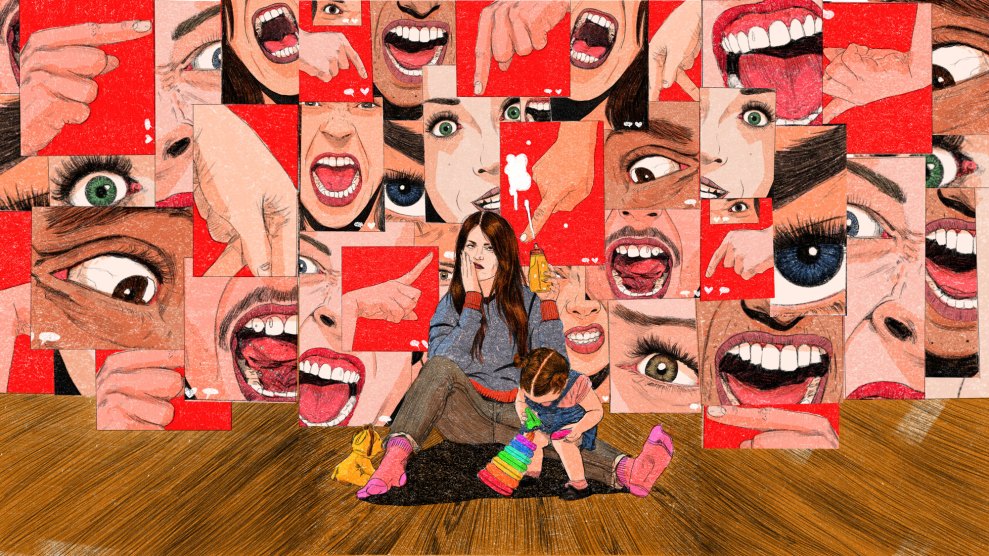

Laura Bush is a lot more popular than her husband, so when many W.-haters see the first lady in photos or on TV, they must wonder, How does she live with him? The speculation about the first marriage has been fueled by Laura Bush’s few titillating suggestions that she might be a closet liberal whose political views, particularly on abortion and homosexuality, directly contradict her husband’s. (She was a librarian, after all.) When I look at Laura Bush, I have more Us Weekly sorts of questions, like, Has she had a face-lift?

But unlike her predecessor, Bush has remained something of a sphinx these past eight years, offering few clues about her views of the world and of her husband. The public sees in her what it wants to see, projecting on to her beliefs that she has chosen to neither confirm nor deny. So author Curtis Sittenfeld has gone ahead and tried to fill in the blanks through fiction. American Wife, timed for release with the opening of the Republican convention, is Sittenfeld’s attempt to imagine the interior life of Laura Bush. Much of the story will be familiar to readers, as it tracks closely to Bush’s biography, down to the cashmere coat she wore to her husband’s first swearing in. Sittenfeld clearly believes the reclusive Laura Bush is, underneath her dowdy exterior, a fascinating character study, but even in Sittenfeld’s skilled hands, Bush proves no more gripping in fiction than she does in real life.

The book resembles Sittenfeld’s first novel, Prep, in that the heroine, Alice Blackwell, is a bookwormish, sensible woman from a middle-class Midwestern family who is thrust, not unwillingly, into the world of the overprivileged. This time the foreign territory is populated with country clubs and political campaigns, but it is not altogether different from the elite prep school of Sittenfeld’s first novel; both settings require the ability of their protagonists to anticipate treachery and to form friendly alliances for survival.

The story begins with Blackwell’s Wisconsin childhood, and the seminal event of her life, which is not her marriage to the future president of the United States, but a car accident in which a 17-year-year old Blackwell kills a young man, for whom she had harbored an enormous crush. While this reads like good fiction, it is one of many parts of the book that is based on Bush’s life. A teenage Laura Bush did indeed run a stop sign and careen into another car driven by a popular classmate she may or may not have wanted to date. He, like the character in the book, died from a broken neck, and Bush has never been able to bring herself to talk publicly about the accident.

Sittenfeld assumes, perhaps correctly, that the accident is why Bush stayed single for so long. (She married George in 1977, less than a year after meeting him, at the age of 31.) The depression that followed this life-changing event seems to haunt the fictional Laura Bush, and helps explain her attraction to the affable dunce, Charlie Blackwell, the restless heir to a political dynasty and a meat-packing fortune who would rather be baseball commissioner than president. Much of the book is devoted to their early courtship and life together.

After marrying into the fancy family, Blackwell leads an existence that is full of the dull minutiae of garden clubs and private-school luncheons. In fact, Sittenfeld goes overboard when it comes to the details of blue-blood culture, though one suspects she gets those details right. (As a graduate of a Western land-grant college, I can’t judge the accuracy of this particular point.) Like Bush, Blackwell eases into her new life seemingly with little nostalgia for her former single, independent self. While she isn’t thrilled with being thrown into public life, she doesn’t hate it enough to walk away, either. When Charlie’s drinking becomes excessive, she decamps to her mother’s for a while. Ultimately she decides to return, in part because she loves Charlie, but also, more tellingly, because she loves her privilege.

This summer, Sittenfeld took some heat from early reviewers incensed that she invented sex scenes between the fictional Laura and George. For all the fuss, those scenes are not only tame but necessary to the plot, as they help illustrate why Blackwell (and, we hope, Laura Bush) stuck with her man. The sex is a refreshing bit of heat in a book dominated by the gloomy details of country-club membership and vacation-home etiquette. There are but a few funny scenes, particularly when Blackwell realizes how spoiled her daughter is becoming. (At one point, Blackwell’s 9-year-old daughter goes into hysterics after the kid in an ice cream truck refuses to let her “sign” for her purchase, the way she does at the country club.) It’s not hard to imagine a young Bush twin staging such a scene when venturing out with the little people.

American Wife is less a story of how Bush/Blackwell manages as first lady than an intimate portrait of the hundreds of small choices that landed her there. As such, the narrative structure doesn’t quite work. The book is conceived as a look back by a 60-year-old woman, but the older woman’s hindsight doesn’t always square with the image Sittenfeld paints of Blackwell’s youth. The transformation of Blackwell from an independent, liberal woman on the verge of homeownership to the dutiful wife of a good ol’ boy with a trust fund is unconvincing, or at least unsatisfying, because its cause is the oldest one in the book: true love. Blackwell’s fairly tenuous personal convictions about politics or other social issues, however liberal, are no match for Charlie, who sweeps her off her feet and liberates her from the cloud of vehicular homicide. But for the politics, American Wife would feel a lot like garden-variety chick lit, the old “opposites attract” romance that could be the stuff of Jane Austen.

The politics, though, are there. All the usual suspects appear, though under different names, including Karl Rove, a version of anti-war protester Cindy Sheehan, even Jeb and Barbara. In crafting Alice Blackwell, Sittenfeld assumes all the things long suspected about Laura Bush and the people around her: that Condi is a lesbian. That Laura has indeed had a face-lift. Sittenfeld does a decent job of trying to craft plausible explanations for some of the mysteries about the Bushes, such as why George W. ever wanted to be president in the first place. She casts Charlie as a fidgety guy with few professional ambitions who replaces drinking with jogging. Alice Blackwell eventually realizes that her husband’s decision to run for governor, and eventually president, has little to do with a desire to serve or a commitment to Republican principles. Instead, he runs because at the age of 40, his Princeton college reunion imminent, he has scant little with which to impress his former classmates. Charlie is obsessed with his own legacy.

Blackwell also suspects that public office appeals to Charlie because he is afraid to sleep alone at night. Getting elected would ensure that he’d never lack for the company of security staff and other aides available night and day. Charlie’s phobia is a clever theme running through the book that Sittenfeld extrapolated from the fact that Laura Bush calls in the president’s fraternity brothers to keep him company so he doesn’t get lonely while she’s traveling.

Sittenfeld isn’t the first writer to fictionalize the life of real and famous women, but she’s chosen a subject with little to offer by way of dramatic tension. Sittenfeld tries to create some around the hot-button issues of the war and abortion. Many pages of the book are devoted to Blackwell’s musing over whether or not she is in some way culpable, and responsible, for the slaughter in Iraq. Even so, the guilt over a foreign war hardly compares to the offerings of, say, the frequently fictionalized Anne Boleyn. Laura Bush is likely to survive her first ladyhood with her head, and her reputation, intact, giving the novelist precious little to work with. If not for the war in Iraq, Laura Bush, with her eight years of polite literary festivals and breast-cancer awareness events, would barely register as a footnote in history. Sittenfeld makes up for her subject’s drama deficit with her ability to capture those little details of blue-blood life, like the Princeton college reunions, that made Prep such a success. But the invented drama can’t hold up the weight of the book; its digressions on the pitfalls of fame and the indignities of having to coauthor books with cats make it seem too long by at least 100 pages.

In the end, if the book disappoints, it’s not entirely Sittenfeld’s fault. The problem may be that Laura Bush just isn’t that interesting. And the bigger problem may lie with her husband. Despite what Code Pink thinks about him, up close, the former Yale cheerleader is someone you probably would end up liking if seated next to him at a party. Laura fell hard for him after only three short months, and her devotion to him clearly trumps any subversive political convictions she may harbor. Indeed, unlike the highly complex Clinton marriage, the Bush union seems solid. Laura and George are apparently quite happily married, and happy marriages are rarely the stuff of good fiction, even when they play out in the White House.