<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/28455143@N08/4826025794/in/photostream/">pagetx/Flickr</a>

Some of the best parenting advice I’ve ever gotten was from a website for prison guards. While researching a story on prison riots, I was browsing CorrectionsOne, a site for corrections professionals whose typical stories have titles like “Mass. man escapes jail wearing only boxer shorts” and “Alternative Uses for Batons” (sorry, that one’s for sworn correctional officers only). There, amid the Taser ads and tales of prison gangs, I came across an article that changed the way I think about being a dad.

The article, “7 things never to say to anyone, and why”, listed common statements used by prison guards and police officers and explained why they make people do the exact opposite of what they’re being told to do. The seven things were:

1. “Hey you! Come here!”

2. “Calm down!”

3. “I’m not going to tell you again!”

4. “Be more reasonable!”

5. “Because those are the rules!”

6. “What’s your problem?”

7. “What do you want me to do about it?”

If you’ve ever been a child or have your own, you undoubtedly recognize those as the greatest hits of the pissed-off parent. As the father of three kids under five, I’ve probably said some variation of each of these phrases dozens, if not hundreds, of times.

The list was compiled by Dr. George “Rhino” Thompson, an English professor-turned-cop whose theory of “tactical communications” has been packaged into a training program called Verbal Judo that’s been used by prisons and police departments across the country. Its core principle is that you should never say what first comes to mind, especially when you’re angry. “The most dangerous weapon you have is not the 9-millimeter or the .357 or the Ithaca pump shotgun,” Thompson says in one of his instructional clips. “No! The most dangerous weapon is the cocked tongue.”

Here’s what he means. Consider why barking the command “Come here!” doesn’t really work. Thompson explains in his article,

You have just warned the subject that he is in trouble. “Come here” means to you, “Over here, you are under my authority.” But to the subject it means, “Go away—quickly!” The words are not tactical for they have provided a warning and possibly precipitated a chase that would not have been necessary had you, instead, walked casually in his direction and once close said, “Excuse me. Could I chat with [you] momentarily?” Notice this question is polite, professional, and calm.

Now substitute the word “subject” with “three-year-old,” and you have a perfect description of how an everyday exchange with your child can rapidly turn into an all-out confrontation. Another familiar example: “I’m not going to tell you again!” This phrase, Thompson says, “is almost always a lie. You will say it again, and possibly again and again!” And there’s the old parental fall-back, “Because those are the rules!” It only encourages resistance, says Thompson. Better to explain the rules and why they’re important: “A true sign of respect is to tell people why, and telling people why generates voluntary compliance.”

Reading Thompson’s article made me realize two things: One, I needed to rethink how I talked to my children. Second, raising kids isn’t totally unlike being a prison guard.

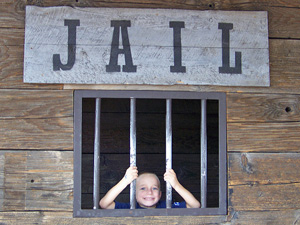

I don’t mean to belittle the hardships of prison or exaggerate the irritations of family life. But as a parent, your job is to care for, feed, and protect people who find themselves in a situation where they don’t make the rules and from which they can’t escape. They’re often not too happy about it. (The other day, my two-year-old pressed up against the glass next to the front door and growled, “I want to get out—jail!”) Being a parent sometimes means enforcing lights out, serving unpalatable meals, confiscating contraband, and punishing infractions by rescinding privileges or using the kiddie equivalent of solitary: the quiet corner/chair/room. You have to manage ever-shifting alliances and rivalries between siblings, with their turf battles, insider lingo, idiosyncratic concepts of fairness, and the fashioning of weapons from household objects. You’re often overworked, outnumbered, and outwitted. Yet if all goes well, your kids do their time and enter the outside world with the values and skills they need to survive. (Hopefully, they never “break parole” and come home again.)

Thankfully, as a parent, you don’t have the recourse to violence that prison guards do. But when you screw up, things can devolve into a Stanford Prison Experiment-type situation: a feedback loop where everyone assumes oppositional roles that feed the tension and conflict.

That’s why, whenever my kids and I have a failure to communicate, I try to think of the advice contained in Thompson’s list of seven things not to say to anyone. Its overall lesson is this: No matter how mad or frustrated you are, you can—and should—communicate in a way that conveys respect and empathy. While such courtesy may feel like a concession of authority, it is actually the best way to keep control of the situation. If you stay calm, your kids are more likely to cool down. (Bonus points if you acknowledge their feelings and explain the consequences of their behavior.) If you escalate, your kids are likely to get even more defensive or obstinate. And that will probably prompt you do something futile, like shouting “Be quiet!” or making elaborate threats you either have to follow through with or lose face. “Natural language”—what our gut tells us to say—”is disastrous,” writes Thompson.

Easier said than done, right? Admittedly, doing some Verbal Judo on your kids would probably a lot simpler if you looked and sounded like Doc “Rhino,” a barrel-chested guy with a shaved head and a raspy voice caused by a bout of throat cancer. (Sadly, Thompson died unexpectedly last week at the age of 69.) But in my sporadic application of his strategies, I’ve been pleasantly surprised. My kids don’t always react with “voluntary compliance,” but I feel a lot better about how I’m treating them, even if inwardly I’m not feeling like the equanimous dad I aspire to be.

Is it weird subjecting your kids to communication strategies designed to talk down angry convicts? I don’t think so. In fact, it’s striking how much overlap there is between Thompson’s message and that of Positive Discipline, a parenting philosophy that shuns traditional yell-and-punish techniques for a more touchy-feely approach in which parents try to understand the emotions behind kids’ actions. Both are based on the idea that empathy and steadiness aren’t mutually exclusive. As Jane Nelson, one of the advocates of Positive Discipline, states, “If you’re being too kind without being firm, you’re probably being too permissive. And if you’re being firm without being kind, you’re probably being controlling and disrespectful.” Or as Thompson succinctly puts it, “Polite civility can be a weapon of immense power!”

Keep that in mind the next time you’re ready to tell your kids to go the f*** to sleep.