Philip Pullman was raised on the tall tales of his grandpa, an Anglican vicar, but his own life has taken plenty of dramatic turns. When he was seven, his mother received a telegram: His father, a Royal Air Force pilot, had gone down over Kenya. “There’s a suspicion that he might have been drinking too much or he might have crashed on purpose because he was in all sorts of trouble—women trouble and money trouble and God knows what else,” recalls Pullman, who is now 66.

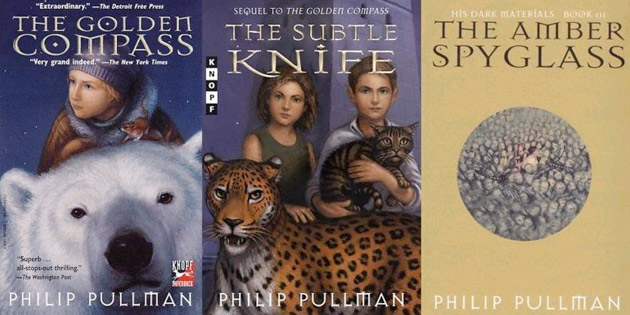

The family relocated to Australia and finally to North Wales, where Pullman devoured books and “grew up intellectually, and emotionally, I suppose.” He later attended Oxford and then spent years teaching English, honing his storytelling chops on captive middle-schoolers and publishing a dozen or so politely received books and plays before hitting pay dirt with His Dark Materials, the wildly popular young-adult trilogy consisting of The Golden Compass, The Subtle Knife, and The Amber Spyglass.

HDM, which has sold well over 15 million copies and been translated into at least 39 languages, has earned Pullman some of the most prestigious awards in children’s literature. In this epic twist on Adam and Eve—replete with angels, witches, and ursine warriors—the church is a malevolent force, characters have animal soulmates called dæmons, and, far from sinful, the loss of innocence of protagonists Lyra and Will is a saving grace.

The series (a prequel called The Book of Dust is in the works) and Pullman’s public antipathy for organized religion (not to mention his 2010 parable, The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ, wherein Jesus is betrayed by his weak-willed twin brother) have raised holy hackles—the Catholic League complained that Pullman was “using a fantasy to sell atheism to kids.”

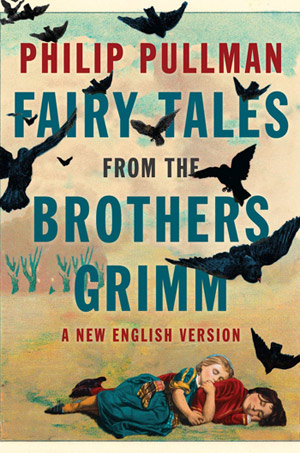

I reached Pullman at home in Oxford to discuss his latest book—a retelling of Fairy Tales From the Brothers Grimm—his writerly superstitions, and what he’d ask Jesus over dinner. (Pullman’s spot illustrations are used with his permission.)

Mother Jones: The Grimm stories have been told and retold for generations. What made you want to return to the originals?

Philip Pullman: It was sort of returning to my roots, really. I wanted the chance to look again at these very famous stories and see what made them work well, whether there were any ways in which they could be improved. Because the great thing about fairy tales and folk tales is that there is no authentic text. It’s not like the text of Paradise Lost or James Joyce’s Ulysses, and you have to adhere to that exact text. I thought there were things maybe I could play around with.

MJ: Were you also hoping to remind us that they don’t belong to Disney?

PP: Disney is a huge presence when it comes to fairy tales because he’s made of them such brilliant artifacts in terms of movie-making. But it’s very hard to ignore what he’s done to them—the characters of the seven dwarves, for example: Sneezy, Happy, all those things. They’re not like that in Grimm, and I didn’t feel that was a very interesting path to go down. But I’m not interested in denigrating Disney or even commenting on him very much. I’m more interested in seeing what I can do with the stories myself.

One thing that did strike me was how different these stories are from novels. You almost never see an adverb—”he said ruefully”—anything like that. That doesn’t happen. You just get what he said, what she did, that absolutely bald statement. And I like that. I wanted to avoid what some modern tellers have done, quite legitimately, to make them more like novels and short stories, to characterize the heroes and the heroines much more than they are characterized in Grimm. I like the psychological flatness of them, the fact that they’re more like masks than individuals.

MJ: It’s clear why some of the old versions have fallen out of favor with parents. “The Robber Bridegroom,” for instance, is pretty disturbing. At what age would you say they’re appropriate for kids?

PP: I’m with the Grimms on this: stories for young and old. You can’t characterize them any better than that. I guess their intention was to have them told around the fire in the evening to the whole family.

MJ: That’s funny, because I actually read your “Cinderella” to a big group of kids around a campfire last weekend, and when the birds pecked out the mean sisters’ eyes, the kids laughed!

PP: That’s right!

MJ: Maybe it was the delivery. Or maybe kids just appreciate biblical justice.

PP: [Laughs.] I think it may be both! But you’re right, the justice of it seems to children correct and right—I mean, we laugh at it! We underestimate children’s ability to know what is a story and what isn’t.

MJ: My kids want to know why all the fathers are so feckless, while the women tend to be greedy or ambitious or evil.

PP: Yeah, people don’t come out of these stories very well, do they? I mean the father in “Rumplestiltskin” is a hopeless man. An even worse case is the father in “The Girl With No Hands.”

MJ: And “Cinderella.” And “Hansel and Gretel.”

PP: Yeah, they’re all hopeless. They’re all unable to protect their children against what happens. They send their them into the wild forest without the slightest compunction. They’re a dreadful lot of beings on the whole. But I suppose if they didn’t do that, we wouldn’t have a story.

MJ: The Grimms originally had the mother as the bad character in some of the tales, and then changed it to the stepmother in later editions. Why is that?

PP: They must have felt that it would be a little too frightening for a child to think that his or her mother could actually abandon them in the forest and let them starve to death. In one story, we see them changing halfway through the text from Mutter to Stiefmutter—they must have forgotten to correct it. But if you were an actor, the mother would be the part to play. The fathers have so little to do; they’re such feeble characters.

MJ: You’re the father of two grown boys, but you tend to prefer girl protagonists. Are you trying to remedy a dearth of—

PP: No, absolutely not! It’s not my business to remedy dearths! It’s my business to tell stories. Lyra and the other heroines didn’t come with placards saying, “Make this a feminist story!” I’m glad people enjoy seeing a female protagonist in a big adventure story, but I didn’t do it for political reasons.

MJ: So I gather that you, not unlike Lyra, your Dark Materials heroine, had a largely absent father and perhaps a slightly Mrs. Coulterish mother. [Mrs. Coulter is Lyra’s mother.]

MJ: So you were a happy kid?

PP: [Laughs.] My mother Mrs. Coulterish? I never thought of her like that, but perhaps you’re right. I remember her getting dressed to go out in the in the evening with sort of early-1950s glamour. The perfume she used to wear was called Blue Grass, by Elizabeth Arden. I still remember it. My mother wasn’t absent, but my father was. My mother married again after my father’s death—another Royal Air Force officer, and a very different kind of man. We went to Australia when I was eight or nine. We lived there for a couple of years, and then came back and lived in North Wales for the whole of my teenage years, the whole of my secondary schooling—The Broken Bridge was a love letter to that landscape of North Wales that I love so much. I learned how to play the guitar a little. I learned how to draw a little. I learned how to write poems quite a lot. I just had a good time reading and reading and reading. So that’s where I did most of my growing up.

PP: Yeah! Very happy in retrospect. I seemed to have spent the whole time either reading, which I loved, or laughing, which I love, or fooling about, which I loved. There was the usual teenage angst: “Nobody understands me” and “I’m the only genius in the world” and all that stuff. But that didn’t get very deep.

MJ: What were some of the books that you couldn’t get enough of?

PP: I loved Kipling—still do, really. The Just So Stories were marvelous, and The Jungle Book. I loved also the novels of Arthur Ransome. He was pretty big over here from the ’30s onwards. Very realistic stories, about ordinary children having adventures in their summer holidays and sailing boats and climbing mountains and that sort of thing. I also loved the Moomin books of Tove Jansson.

MJ: My family loves the Moomins!

PP: Oh, good. I think they’re a particular taste. You have to hit the Moomins at the right moment and then you’re a Moomin fan for life.

MJ: What are you reading now?

PP: A very fascinating book by Robert Caro, the biographer of Lyndon Johnson. I’m reading his first book, The Power Broker, about Robert Moses and his history as a builder of New York. That’s amazingly good. I’m a great fan of James Lee Burke. I’m reading the first of his Dave Robicheaux novels, Neon Rain. I think I’ve read most of the others. I read a lot of books of crime and thrillers. James Lee Burke is a particular favorite of mine. He’s a wonderful writer.

MJ: Lost innocence is obviously a major theme in your work. Does your own literary loss of innocence, your experience as a storyteller, interfere with your enjoyment of reading?

PP: That’s a very interesting and a very big question. I thought of this a lot when I was writing His Dark Materials. The central moment in the account of Adam and Eve in the book of Genesis is when they sort of come to after they’ve eaten the fruit and they realize they’re naked and try and cover themselves with fig leaves. That seemed to me a perfect allegory of what had happened in the 20th century with regard to literary modernism.

Literary modernism kind of grew out of a sense that, “Oh my god! I’m telling a story! Oh, that can’t be the case, because I’m a clever person. I’m a literary person! What am I going to do to distinguish myself? I know! I’ll write Ulysses.” [Laughs.] Actually, I don’t think that was Joyce’s motive—but a lot of modernism does seem to come out of a fear of being thought an ordinary storyteller. So they tell it backwards and they tell it in the present tense and they cut loose the pages and shuffle them around—all that kind of stuff. When I first started writing, I tried to do that sort of thing, but I realized that there was a limited value in that. And it also made it difficult to read, and I didn’t really want my books difficult to read. This is the value for me of writing books that children read. Children aren’t interested in the least about your appalling self-consciousness. They want to know what happens next. They force you to tell a story.

MJ: I gather you kind of used your middle-school students as guinea pigs.

PP: I didn’t care about them. [Laughs.] If it kept them quiet for half an hour, good, that’s fine. My real purpose in telling them stories was to practice telling stories. And I practiced on the greatest model of storytelling we’ve got, which is “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey.” I told those stories many, many times. And the way I would justify it to the head teacher if he came in or to any parents who complained was, look, I’m telling these great stories because they’re part of our cultural heritage. I did believe that. But mainly I wanted to practice again that bit where Achilles looks over the walls of the Greek camp and looks across as the sun’s setting and sees the man who’s just killed Patroclus! That was the best training I could possibly have had, and it rid me forever of self-consciousness as a storyteller.

MJ: What were some of the tricks you employed to tame your students?

PP: The range of individuality in children is infinite, but every class of children seemed to have the same groups. And there was a chief girl and a chief boy—a girl that all the other girls of that age looked up to and imitated and a boy that all the boys looked up to and imitated. I realized that if I got them on my side and exclusively taught them for a couple of weeks, maybe for the first full term, then I wouldn’t have any trouble. Teachers often make the mistake of thinking they’re the boss of the class; they’re not. The boss of the class is sitting down there somewhere.

MJ: So, I’ve read that you were close to your grandfather, an Anglican vicar.

PP: He was a lovely man. He was kindly, funny in the sense of being little bit physically clumsy. [Laughs.] I remember one year when we were having a box of fireworks, he dropped a match into it and of course, they all went off. That was sort of thing Grandpa did. He was a great storyteller. All the stories of the Bible that I know came to me first from my grandfather’s lips. He would see stories in everything. We would be going out for a walk, and we’d come to a long, straight stretch of road with a tree at the end of it: “That’s the Trail of the Lonesome Pine. That’s what this road is called, boys.” [Laughs.] “That oak tree there? That’s the very one Robin Hood used to hide in.” He told stories very easily and very generously, so I loved him for that. He was a simple man, a Victorian; he was born in 1890-something. He saw no reason and had never seen any reason to question his Christian faith. His faith was strong and simple and that’s it. And I, like his other grandchildren and the children in his parish, sheltered underneath it.

MJ: So you believed in God when you were a little kid?

PP: Yeah, of course, because Grandpa told me he existed.

MJ: But Grandpa made up stories.

PP: I kind of believed in them as well. [Laughs.] No, there was a different quality to the biblical ones: They were really true. Jesus really was there and David really did go down to the riverbed and choose some stones.

MJ: When did you know you were an atheist?

PP: Well, I still don’t. Let me put it like this: I don’t see any sign of God in this world, in the place where we live and things we know. It can all be explained to my mind perfectly satisfactorily without God. But in the great darkness beyond this little spark of light where I live, of course there may be all kinds of things. There may be a god. So I’m really an agnostic.

MJ: You recently told a young reader that the person you’d most like to have dinner with is Jesus. What would you ask Jesus?

PP: Yeah, well, he’s the most fascinating character in history, really—the character who’s made more difference to the world than anyone since him. I daresay that Muslims would say Muhammad was that character, but I think Jesus had a sort of 600-year start on him. [Laughs.]

I’d like to hear what kind of Jew he was, for example, how pious he was.

According to what he says in the Gospels, he was absolutely certain that the end of time was coming, that the kingdom of heaven was coming within his lifetime—if not within his lifetime, then within the lifetime of those who were listening to him.

Like many prophets—and we’ve seen several in our own times who say, “Come up on the top of the mountain; the flying saucers are coming on Tuesday and then we’ll all go and we’ll all be taken up to Venus and we’ll all live happily every after,” and they all go up to the top of the mountain and the flying saucers don’t come, so on Wednesday they kind of trudge down rather disconsolately: “Well, we got the timing wrong. It’s next October”—Jesus was in that unfortunate position. The crucifixion saved him from that. He never had to deal with the fact that the kingdom of God wasn’t ever going to come. His disciples, of course, had to deal with it, and little by little they had to realize that it’s a metaphorical thing. Well, that’s not what Jesus meant. I’m fairly sure he meant it literally. But he must have been the most fascinating man.

MJ: So would it be fair to say you’re a fan of Jesus and an enemy of the church?

PP: Uh, yes. That’s pretty much where I am. If we all gave all our goods to the poor, the church would fall apart. If we all hated our father and mother, as Jesus told us to, there’d be an end of the church’s emphasis on the family as being the one important thing holding the whole society together. There are all sorts of ways in which the church’s teachings contradict directly what Jesus says in the Gospel.

MJ: You have a superstition involving “story sprites.” Tell me about that.

PP: The state of mind which I put myself when I tell a story is one in which superstition flourishes very easily. And I welcome that because it helps me. A story, to me, has a particular sprite, like the angel of the spirit of that story—and it’s my job to attend to what it wants to do. When I tell the story of Cinderella, the sprite does not want me to make it into an allegory of the fall of communism. The sprite would be unhappy if I did that. I can’t put it any more clearly than that because it’s a strange area and I’m not very sure about it myself. But I’m perfectly happy about being superstitious and atheistic.

MJ: Any other notable superstitions?

PP: Yeah! I’ve got a number of private superstitions which I’ve discovered work.

MJ: Do tell.

PP: Uh, well, I’m superstitious about the paper that I use, for example. I’ve written all my novels on a paper of a particular size with lines of a particular distance apart and with two holes in the paper for the folder clip. There was a time a few years ago when I couldn’t get any two-holed paper and all they had in the shops was four–holed paper. And I thought, “This is terrible!”

It was when I was finishing The Amber Spyglass. I couldn’t buy any paper with two holes in it and I had two or three chapters to write. Well, I found the answer! I found these little stickers that you write a price on and stick them on a back of a book—I got a whole bunch of those and I covered up the top hole and the bottom hole. [Hilarity ensues.]

MJ: That is so funny!

PP: Yeah, that’s an example of utter irrationality. But it worked for me.

MJ: Is it also true that you write precisely three pages a day?

MJ: It’s interesting you don’t use computer to write your novels, since it makes the editing so much easier.

PP: Uh, yes. When I’m in the middle of writing a novel, I write by hand on that sort of paper, and when I get to the bottom of the third page, I finish the sentence at the top of the next page. Or if I finish the page with a sentence, I write that sentence on the next page, so the next page is already defeated! It’s not just a blank page looking at me. But when I’m doing a film script or something, I’m doing that on the screen because you use special software for scripts and so on. So I do it until I’ve done roughly the right amount.

PP: Yeah, too easy!

MJ: You’re a fierce defender of public libraries. Do you feel strongly about how readers come to your work?

PP: Yeah, that is a good question. The e-book revolution has made it very easy to pay writers a good deal less than what their work is worth. I do strongly believe that we writers ought to hold out for much better royalties.

MJ: J.K. Rowling reportedly sketched out the Potter series before she wrote the first book. I gather that’s not how you operate.

PP: Well, that’s what she said. [Laughs.] How shall I put this tactfully? It would interest me a great deal to know that J.K. Rowling had the whole how-many-thousand pages of it sketched out before she began to write it. One of the ways in which writers most show their inventiveness is in the things they tell us about how they write. Generally speaking, I don’t like to make a plan before I’ve written a story. I find it kills the story—deadens it, makes it uninteresting. Unless I’m surprised by something in a story, the reader’s not going to be surprised either.

MJ: Okay, so you’re sitting there staring at your two-hole paper…

PP: Well, I have an idea, usually a visual image of some sort. A setting. A particular, I don’t know, urban scene, a particular time of day. Something that grips my imagination for some reason.

MJ: What was it for His Dark Materials?

PP: It was this child going into a room where she wasn’t supposed to be and being trapped there and hearing what happens.

MJ: How did your notion of a dæmon come about?

PP: That just came about because I’d written the opening of the book about 15 times without the dæmon and it wasn’t working. A girl goes into a room, looks around, somebody comes in and she’s trapped. But it wasn’t working and I didn’t know why. Then Raymond Chandler’s advice came true: “When in doubt, have a man come through the door with a gun.” In this case it was a dæmon. When in doubt, have a dæmon! Wow, yes! Now Lyra can talk to the dæmon. And the dæmon can contradict her and say, “No, don’t go in there, we’re not supposed to.” It was suddenly much more dynamic.

MJ: You created a foil, essentially.

PP: That’s right. Someone to converse with, an accomplice, all sorts of things. And it wasn’t until much later that I realized what the dæmon could do, and that adult dæmons were different from children’s dæmons because they stopped changing. That was the real moment: not discovering the dæmon but discovering that adults’ dæmons had stopped changing. That’s when I realized that I’d got hold of this big innocence and experience idea. The most exciting thing that’s ever happened to me as a writer was realizing that.

MJ: What form would you prefer your own daemon to take, and what form do you suppose she might actually take?

PP: That’s a good point: You can’t choose, can you? I would like my dæmon to be more photogenic than I am. Then she could take my place in the photographs I have to submit to. But I think my dæmon is probably one of those birds that steal things: a magpie, a jackdaw, a raven. She’s a scruffy, greedy, idle, old thing, but she has a very sharp eye for a story.

MJ: Did you fathom how alluring the notion of a daemon—this literal animal soulmate—might be for your readers?

PP: I had no idea. I had hoped people would like it. But you see, my previous books hadn’t sold very well. I had a small readership. I had a few good reviews. And I thought this would be the same. I thought it would sell maybe two, three thousand if I was lucky.

MJ: The success of the books took you entirely by surprise?

PP: Absolutely, completely by surprise. I was amazed—delighted of course.

MJ: Tell me about the mail you receive.

PP: There was a period when I had a great deal of mail specifically about His Dark Materials. Before the third book was published, that’s when I got the most. When is it going to come out? Hurry up, hurry up! What happens next? To which I could only reply, “You’ll get it when it’s finished.” I get a small amount of mail from people who think I’m going to hell—and deservedly, I may say, for having seduced so many children into the powers of evil. That kind of letter is less common than it was. I think Harry Potter distracted a lot of those readers.

MJ: There have been no less than 18 books written about His Dark Materials.

PP: Eighteen! Is that right?

MJ: They’re all on your website.

PP: Oh, right. Well you’re a more assiduous reader of my website than I am a writer of it.

MJ: Have you read any of them?

PP: No. It would either make me think what a great guy I was or else make me think, “No, they got it all wrong; let me write in and correct it.”

MJ: One thing that struck me was that the alethiometer, the all-knowing device that Lyra comes to master, could be a storyteller’s curse. It’s a built-in deus ex machina.

PP: That’s one of the reasons why I had Lyra lose it in the end—it was getting too powerful. If you know what’s going to happen next, it ruins the story. She’s using it still in the book I’m writing now, the sequel, but she’s having to do it consciously, with all the reference books, and it’s a real chore. That way it works for me as a storyteller.

MJ: What else can you tell me about The Book of Dust?

PP: It’s progressing. It’s taken me a while to get started because I was doing lot of other things, including film scripts, shorter books, my Grimm tales. But now the way is clear and I’m very happy with the way it’s going.

MJ: Speaking of films, just before The Golden Compass movie came out, one writer predicted that your characters would shortly be as famous as Dumbledore and Gandalf. Was it a blow to you that films were never made of the other two books?

PP: I completely expected it. I’m pretty surprised that they made the first one, actually.

MJ: Why?

PP: Because of the implications. I don’t think they realized what they’d got. When they saw where the story was going, it was quite clear that they weren’t going to…

MJ: Kill off God?

PP: [Laughs.] You could put it like that, yes.

MJ: Has there been any interest in making another go at it?

PP: I’m quite tempted by the idea of doing it as a 24-part TV series like Game of Thrones. It doesn’t need the scale of the movie screen, it needs the length of a TV series.

MJ: I would definitely watch that.

PP: I would watch it too. I think it could be done.

MJ: The conservative British columnist Peter Hitchens calls you the anti-C.S. Lewis. Did you ever view His Dark Materials as a literary response to Narnia?

PP: No. I’ve spoken and written about Narnia. I didn’t feel the need to address the Narnia question at all in His Dark Materials. This is my story, not C.S. Lewis’s story—and not an answer to it either.

MJ: You’ve also been critical of Tolkien, calling his work “infantile.” What’s your take on, say, the Harry Potter books—or The Hunger Games for that matter?

PP: I haven’t read them, partly because fantasy actually is not something that interests me very much. The only fantasy that I’ve felt to be emotionally satisfying is a book called A Voyage to Arcturus by David Lindsay. He was a strange writer, Scottish writer. It was published around 1920. It’s a very crude and primitive sort of science fiction. It’s about morality—good and evil—and he deals with it in a way that is so forceful and so powerful that it sweeps aside any doubts you may have about the validity of the genre, in a way that Tolkien certainly doesn’t. Tolkien seems to me reactionary, conservative, fearful of a modern world. Fearful of anything that isn’t sanctioned by the passage of long eons of time. I think what I’m doing in His Dark Materials is politically the reverse of that.

MJ: On your website you say, “I’m not in the message business; I’m in the ‘Once upon a time’ business.” But your stories and your public antipathy for the church have made you a lightning rod. Can you have it both ways?

PP: It’d be nice! Although I say it I’m overtly not in the message business, the way you speak of the characters in your story shows what you think of the values of conservatives‚ or evolution, for example. It shows where your moral center is. So you are in the message business whether you like it or not.

MJ: Given what you’ve written about religious fundamentalism, you must take a rather dim view of our Republican Party.

PP: I look at the state of the American politics and I scratch my head in wonder. How can the Republican Party, any party, have fallen into to such a state of self-destructiveness—self-destructive stupidity? How is it possible? I don’t know. It’s an absolute mystery to me.

MJ: Hey, it keeps Mother Jones in business!

PP: Yeah. [Laughs.] I guess it does. But it reduces people of my acquaintance, here and in the States, to open-jawed wonder that any party can behave as badly, as stupidly, as simply destructively as the Republican Party and still be in business as a serious political party.

MJ: Let’s end with a question about endings. It strikes me that the Grimms’ endings could use some improvement—at the very least a bit more variation.

PP: “They got married and they lived happily ever after” really is the beginning of another story entirely, isn’t it?

MJ: Like how did they get married and live happily ever after. I need to know that!

PP: [Laughs.] The answer is that they didn’t. But then it became a novel.