The hit TV series Breaking Bad, which, in case you hadn’t heard, concluded its incredible five-season run last night, is known for its disorienting opening scenes—brief cryptic bits of foreshadowing before the first titles flash on screen with that now-iconic guitar and bass snippet. The technique has been employed in other shows, but never with such regularity and success as in Vince Gilligan’s Emmy-dominating opus.

But one of the teasers, appearing mid-way through Season 2, has stood out from all others: It’s a video of the Mexican band Los Cuates de Sinaloa performing a narcocorrido (drug anthem) honoring Heisenberg, Walter White’s drug-trafficking alter ego. (White is portrayed by the actor Bryan Cranston.)

If you don’t speak Spanish, the song sounds like an upbeat Mexican folk ditty. But the lyrics allude to Heisenberg’s blossoming meth business, which, at this point in the series, has left the Mexican cartels fuming over lost territory and profits. Shots of Heisenberg’s nonpareil blue meth, guns, fat stacks of cash, and a trail of bloodied bodies flashes over Los Cuates’ frenetic playing.

The band’s name, which means Friends of Sinaloa, refers to the Sinaloa Cartel—the biggest, richest drug-trafficking and organized-crime syndicate in the Western hemisphere. While the Heisenberg paean, “Negro e Azul,” is an ode to a fictional character, Los Cuates is a real narcocorrido act, part of a genre called Movimiento Alterado. This traditional-sounding music rhapsodizing drug kingpins and other bad guys has gained popularity on both sides of the border.

Opening this fall, a gritty new documentary, Narco Cultura, showcases the influence of the cartels on Mexican pop culture, as well as the bloody reality their power wreaks. In Juárez, Mexico, the nights glow blue and red as the city’s forensics teams collect the bodies of victims caught up in the drug war. Early in the film, a group of young boys looks from behind the police tape, piecing together what happened from the things they overhear: Some hooded guys with AK-47s lit up a truck, “liquidating” the man inside. “That’s how they killed my uncle,” one boy intones, the police lights flashing in his eyes. “He was going to church. He was just walking and got shot. He choked on his own blood.”

Watch the trailer:

Starting in 2006, after former president Felipe Calderón declared a war on drugs, the city of Juárez (population 1.3 million) gained infamy as the most dangerous city on Earth—at least in a country that wasn’t at war. In 2007, 320 murders were recorded in Juárez. By 2010, there were 3,622, an average of 10 homicides per day. Just 50 meters across the Rio Grande, authorities in El Paso, Texas, recorded only five homicides that year, making it the safest city in America.

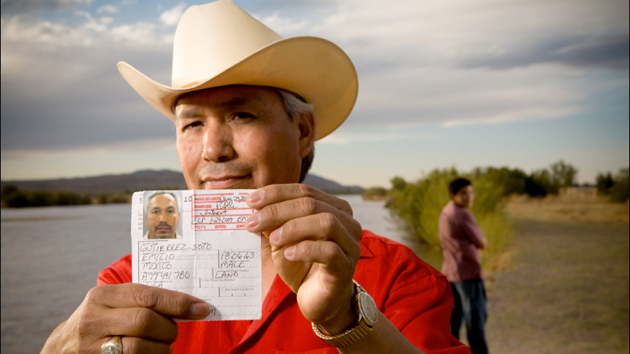

In Narco Cultura, the award-winning photographer-turned-filmmaker Shaul Schwarz focuses on the tales of two men: Richi Soto is a soft-spoken Juárez native who works as a crime scene investigator. Edgar Quintaro, a narcocorrido singer in Los Angeles, glorifies the criminal life in his band, BuKnas de Culiacan, and then returns home to his wife and babies. Soto and his fellow investigators, fearing they’ll be the next target, often keep their faces covered while they work. That’s hardly paranoia—in one year, three members of the CSI team were assassinated.

Back in LA, Quintaro hops into an SUV with Ghost, a gangbanger who hands him a roll of cash in exchange for a ballad in his honor. Back home, Quintaro hands the money to his young wife, who tucks it away in the sock drawer. He then takes his toddler outside for a bike ride and sings him a lullaby: “We’re bloodthirsty, we’re crazy and we like to kill.”

While the glorification of criminals through pop culture is nothing new, the narcocorrido music can be disarming. To a non-Spanish speaker, William T. Vollmann wrote in Mother Jones, las balladas prohibidas are indistinguishable from every other “happy song” on the jukebox. They are folksy, old-fashioned and frankly, kind of cheesy—something grandmas dance to. Yet, even though the music is banned by radio and TV stations in both countries, BuKnas packs nightclubs from Seattle to Atlanta, and its fans know all the words. It’s the equivalent of gangsta rap with a tuba and accordion.

Flimmaker Schwarz is as bold as he is talented in framing a shot. He manages to finagle ridealongs with cops and drug dealers alike, gaining intimate access to their homes and families. Yet he provides an unflinching look at the trade’s brutality—corpses are shown in all manners of repose, and streets literally run red as shopkeepers mop blood down the storm drains. All of this is juxtaposed with the music and its fans—drunken couples swooning and swaying to the tuba and guitars, girls in school uniforms clutching notebooks as they watch their pop idols film brutal scenes for the latest straight to DVD movie—giddily hoping for an autograph, maybe even a kiss.

Vollmann wrote that the fans view these narco-traffickers as Robin Hoods, powerful men who laugh in the face of authority and give back to their communities. But the only thing the dealers give back in Schwarz’s film is terror and violence. “The kids look up to the narcos because they represent an idea of success and power and impunity,” says Sandra Rodriguez, a reporter for Juárez newspaper El Diario. “If you can kill a person, that is limitless power.”

As Rodriguez points out on camera, for every 100 murders, only three get investigated—and even fewer result in convictions. She sees the popularity of bands that gleefully sing of beheading narcs and gunning down cops as a sign of the Mexican culture’s decline. “For me, it’s like a symptom of how defeated we are as a society.”

If BuKnas’ packed houses and Los Cuates de Sineloa’s appearance alongside the cast of Breaking Bad on Conan last week are any indication, the bloody Movimiento Alterado phenomenon is only going to get bigger.

Narco Cultura opens in select theaters November 22.