Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios/ZUMA Press

For many people who grow up with their noses in books, meeting their favorite character is the ultimate fantasy. Mallory Ortberg isn’t one of those readers.

“They’re such assholes,” the co-founder of feminist website The Toast says when I ask her who in the Western canon she’d most want as a texting buddy. “I don’t know that I would want any of them to have my phone number, because they would all feel very free to text me at 2:00 in the morning just screaming.”

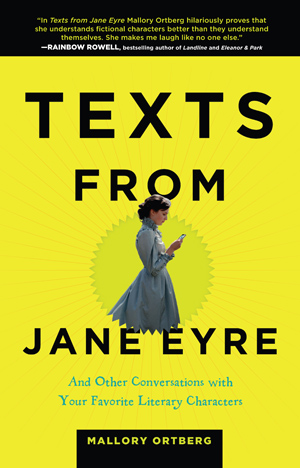

Ortberg has put a lot of thought into the phone etiquette of literary personalities. Her book Texts from Jane Eyre, published November 4, features imagined exchanges between characters both classic and modern. From Hamlet whining about the relish on his tuna fish sandwich to Scarlett O’Hara sexting Ashley, the conversations are both LOL-worthy and true to the spirit of the works they parody.

Mother Jones: Where’d you get the inspiration for your first “Texts From” piece?

Mallory Ortberg: This is actually one of the only projects I’ve ever done where I can 100 percent pinpoint where it got started. It was back on The Awl when [The Toast co-founder] Nicole Cliffe was doing her Classic Trash series, and she was talking about Gone With the Wind, and somebody in the comments said, “I’m from the South and it’s actually exactly like this now, except everybody has cell phones.”

As soon as I saw that I was just like, “Oh God, the idea of Scarlett O’Hara with the ability to get in touch with all of her friends at any time and ask them for favors is horrific and vivid and amazing.” And I immediately wrote “Texts from Scarlett O’Hara” in like 10 minutes. So weirdly something good has come out of Internet comments—I got a book deal from it.

MJ: Would you say your own texting style is similar to the way the book is written?

MO: As a medium, texting is a really great way to get out of stuff when you know that you’re wrong, but you want to minimize having to make eye contact with someone as you bail on them or tell them that you fucked up. So I have definitely in my in life used a text to be like, “Oh hey, dude, I’m sorry, turns out I can’t make it after all!” like five minutes before I’m supposed to be somewhere.

MJ: When did you realize that you were funny?

MO: Oh man. I’ve always thought that I was funny. The world has not always agreed, but…I’ve always just been like, “Yes, absolutely, let’s do this! I will make jokes come hell or high water! Even if no one laughs.”

There were a lot of different influences on me. I started reading P.G. Wodehouse when I was about twelve, and that was huge for me. And certainly the classics like Monty Python, The Kids in the Hall, A Bit of Fry and Laurie, very dry British humor. But also like Robert Benchley and James Thurber, your mid-century American humorists. And then I remember when I was a little kid my brother and I would stay up and watch Comedy Central specials and we saw Maria Bamford together. It must’ve been her first standup special, because I think it was 1999—she was a kid. And I just remember being captivated that someone could be that weird in a way that felt so universal.

MJ: Was the process of coming up with jokes for this book similar to how you come up with stuff you’ve done at The Toast? If you’re working on, say, Women in Western Art History, is that just you sitting in front of Google Images looking at old paintings until something comes to you?

MO: Often it is, yeah. I love the art history ones because it’s so little work for me. There’s so many paintings that when I look at them, the look on the lady’s face is like so clear and her body language and her posture or their physical situation is so immediately recognizable. Anyone who’s been in a conversation they didn’t want to have, or been getting harangued by a little kid they didn’t want to pay attention to or been tired and wanted to go to bed is just like, “Yes, of course.” You can instantly see in this person’s face the universal sense of “Oh God, please leave me alone.”

MJ: How did you know there would be an audience for something like that?

MO: It was really a calculated risk. At the time that we started it, Nicole was coming off about a year or a year and a half as co-editor of The Hairpin, and I had been working as the weekend editor for Gawker and also a place called The Gloss. So by the time we started The Toast it wasn’t a complete leap in the dark. We weren’t completely unknown. The time felt right enough that we were like, “Let’s give this a year, and if it turns out to be the kind of thing that six people love and adore and nobody else cares about, we’ll say that we had a fun time trying something new and we’ll call it quits.” But it was kind of—it wasn’t a shock, but it was a really pleasant surprise that within the first couple of weeks it was clear to us that there were people who felt like The Toast was home for them.

MJ: Do you have a favorite thing that The Toast has published so far?

MO: I have a lot of favorites. We had a woman who wrote a piece about her first name. It was also about her Muslim-American identity and being the daughter of immigrants, and it was just thoughtful and stirring and profound, and it really moved me. That’s definitely up there for me. I also love Nicole’s blind items from Ontario. That’s so weird. That’s so Canadian. Just the blind items about, like, who was late to the potluck and what person was growing medical marijuana. I just love everything Nicole writes.

MJ: So, you’re from the Bay Area—how do you feel about artisanal toast?

MO: You know, when I hear “artisan,” I think of being in social studies and learning about the old classes and the rise of merchants during the late Middle Ages. So that’s what I think of—I picture an old-timey guy at a fucking loom, maybe like trading with some Dutchmen.