In early 1945, the federal government started to open the internment camps where it had held 120,000 Japanese Americans for much of World War II. Seven decades later, photographer Paul Kitagaki Jr. has been tracking down the internees pictured in wartime images by photographers like Dorothea Lange (who photographed Kitagaki’s own family—see below).

So far, he’s identified more than 50 survivors, often reshooting them in the locations where they were originally photographed.

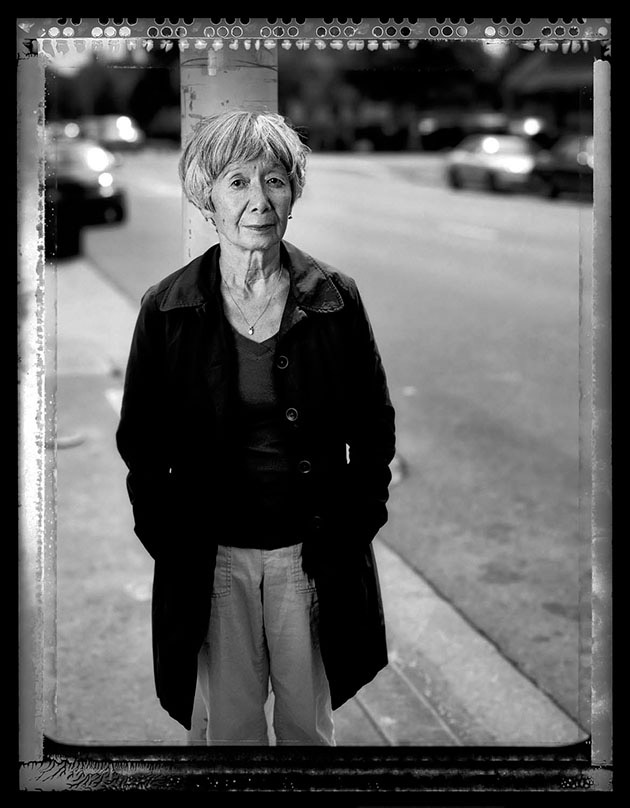

Seven-year-olds Helene Nakamoto Mihara (left, in top photo) and Mary Ann Yahiro (center) were photographed by Lange as they recited the Pledge of Allegiance outside their elementary school in San Francisco in 1942. Both were sent to the Topaz Internment Camp in Utah. Yahiro (right, in bottom photo) was separated from her mother, who died in another camp. “I don’t have bitterness like a lot of people might,” she told Kitagaki.

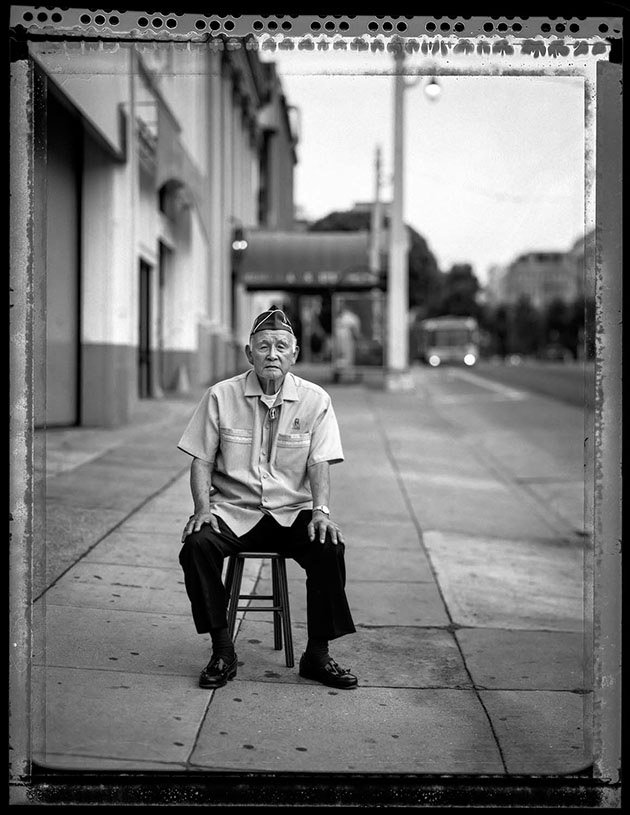

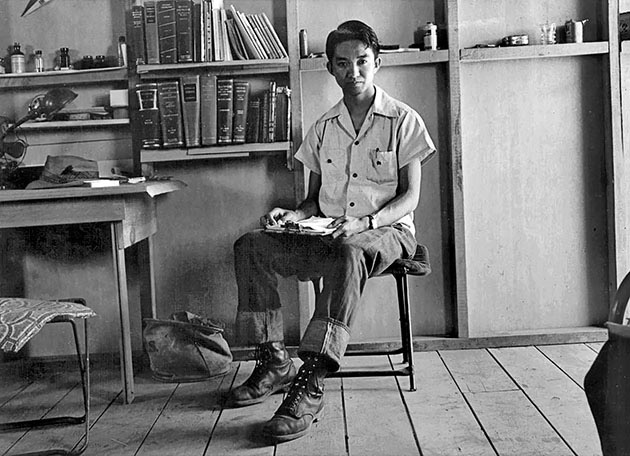

Lange photographed 19-year-old Mitsunobu “Mits” Kojimoto in San Francisco as he waited to be sent to the Santa Anita Assembly Center in Arcadia, California. “We were being kicked out of San Francisco,” he recalled to Kitagaki. “It was kind of shocking, because as you grow up you think you are going to have certain rights of life, liberty. And to be sitting there was very disheartening. I was really wishing that somebody would come and save us. We were citizens, but now we were not.”

Kojimoto volunteered for the army and received a Bronze Star for his service in France and Italy. “I felt, I’m going to volunteer,” he said. “Why not?…We were behind barbed wire, and we should put our best foot forward and volunteer.”

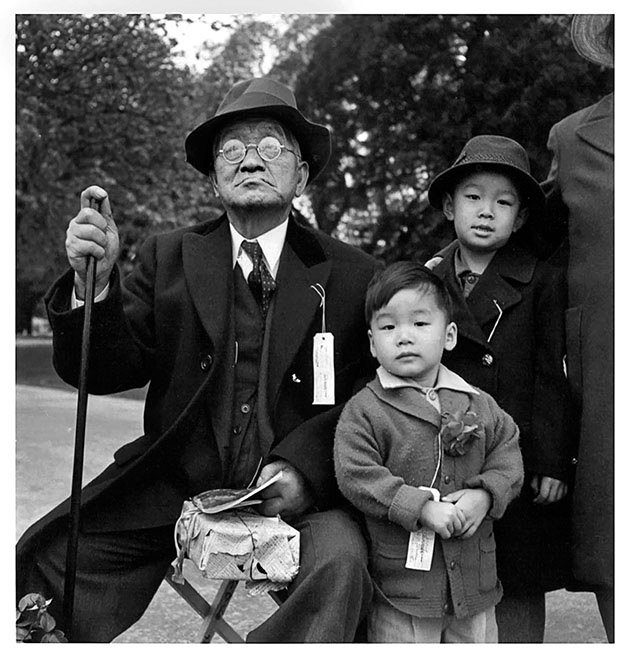

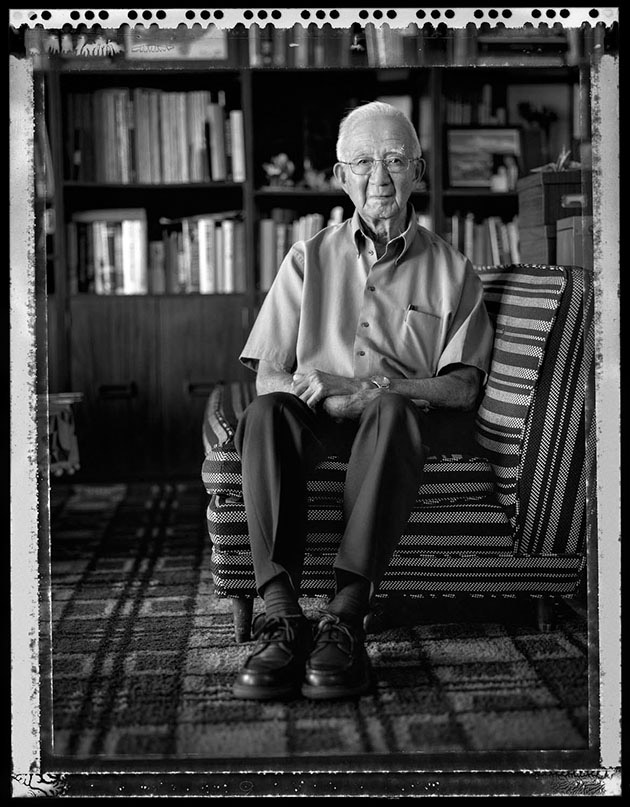

In one of the best known photographs of Japanese American internment, 70-year-old Sakutaro Aso and his grandsons Shigeo Jerry Aso and Sadao Bill Aso wait to be deported from Hayward, California, in 1942. “When I look at the picture, I can see my grandfather realized that something terrible was happening and his life was never going to be the same again. That was the end of the line for him,” Bill Asano told Kitagaki about his grandfather. His brother, Jerry Aso, agrees: “So, [grandfather’s] dream of coming to the United States, his dream of making a life, his dream of having his children working in this business, to support them all were totally dashed.”

“My parents and my grandparents seldom talked about the internment experience, even though I know that it was a searing memory,” said Aso. “And I think because it was so searing, that they didn’t want to talk about it. But I think also, also the idea that, if you try to explain the unfairness of the whole situation, the explanation itself kind of falls on deaf ears.”

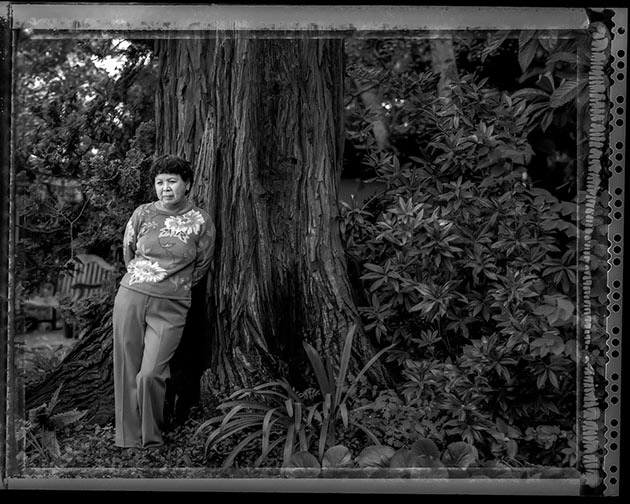

Below, seven-year-old Mae Yanagi before being sent to the Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, California, where her family spent several months in a horse stall before being shipped to a camp in Utah. The Yanagis left their home and nursery business in Hayward, California, in the care of a businessman. “When we got back, it had been sold,” Mae Yanagi Ferral told Kitagaki. “It was there, but somebody else was living there. We didn’t talk about it.” Her father had to start over as a gardener in Berkeley. “He had the most difficult time with the relocation and he never accepted the premise that they were doing it for our benefit. For many years he was very angry. My father felt the injustice of the interment, and my older siblings really felt the injustice of it. We just didn’t say anything about it.”

Harvey Akio Itano was interned in 1942, forcing him to miss his graduation from the University of California, Berkeley, where he was awarded the school’s highest academic honor in absentia. In the summer of 1942, he was allowed to leave Tule Lake War Relocation Center to attend medical school. Itano went on to help discover the genetic cause of sickle cell anemia while working with Dr. Linus Pauling at Cal Tech in 1949. He also worked as the medical director of the US Public Health Service and as a pathology professor at University of California, San Diego. In 1979, he became the first Japanese American to be elected to the National Academy of Sciences. He died in 2010.

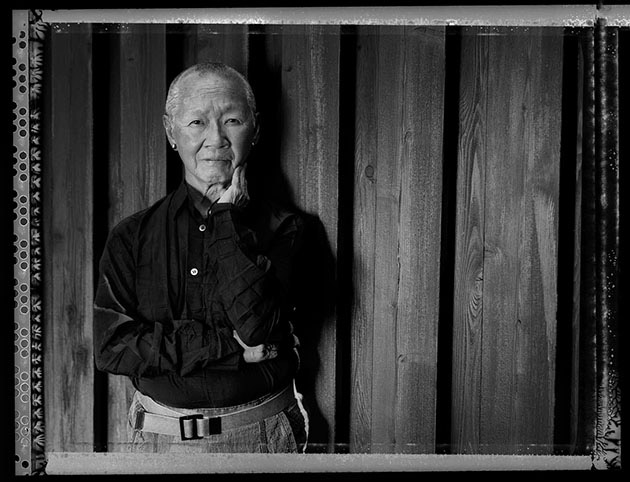

“We should be careful not to incarcerate whole groups of people, as they did,” Anna Nakada told Kitagaki. “We need to be very wary of that.” As a girl, Nakada was photographed during a 1945 performance at the Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah. After the war, Nakada became a master of ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arrangement. Internment, she reflected, “displaced our family in kind of a positive way rather than negative. It didn’t drag us down. In fact, it gave us some chances.”

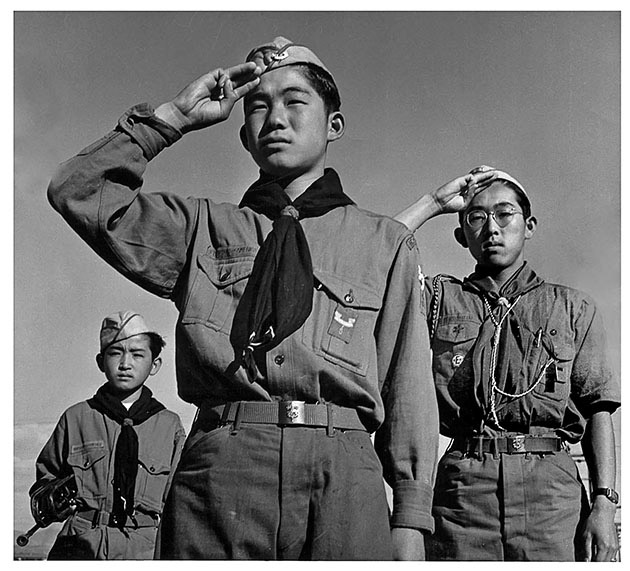

Kitagki located former Boy Scouts Junzo Jake Ohara, Takeshi Motoyasu, and Eddie Tetsuji Kato, who had been photographed during a morning flag raising ceremony at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming. “I didn’t feel anything until later on,” said Ohara, who later became a pharmacist. “I got kind of angry, because of all the experiences that we went through, the losses, not for myself but for the parents and the older guys that had already graduated high school. You start to think about those guys.” After Takeshi returned home, he became an electrical engineer. “I think for us young guys it was not too bad,” he said. “They fed you, they clothed you. It’s just the persecution from you being the enemy, that’s the only thing that would bother you.”

Ibuki Hibi Lee stands in the exact location in Hayward, California, where she and her mother waited to board a bus with their belongings 70 years earlier. Her parents, Matsusaburo Hibi and Hisako Hibi, were artists who documented life in their internment camp in Utah. “You have to think of camp from the view of injustice,” Lee said. “And it was really an injustice to Japanese Americans and those who were citizens. It had to do a lot with economics, racism and politics.”

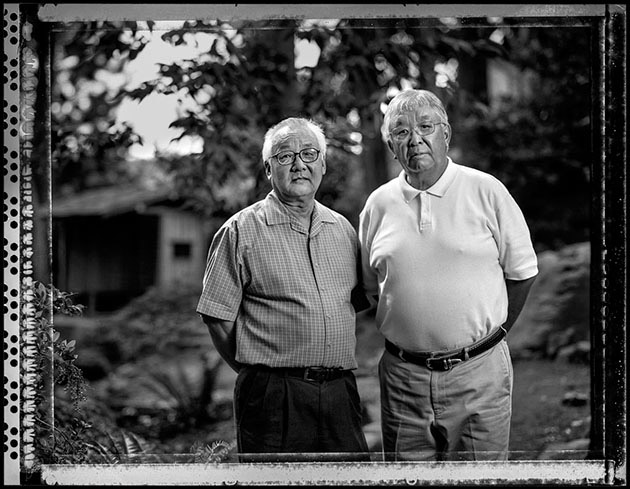

Lange photographed Suyematsu Kitagaki and Juki Kitagaki as they sat with their children, 11-year-old Kimiko and 14-year-old Kiyoshi, at the WCCA Control Station in Oakland, California, before being detained in May 1942. In the photo, a family friend hands Kimiko a pamphlet expressing good wishes toward the departing evacuees. The Kitagakis were later sent to the Topaz Internment Camp in Utah.

More than 60 years later, Paul Kitagaki Jr. joined his father and aunt outside the same Oakland building where they had been photographed with his grandparents. From left to right: Agnes Eiko Kitagaki (his mother), Kimiko Wong (his aunt), Paul Kiyoshi Kitagaki (his father), Sharon Young (his cousin), and Paul Kitagaki Jr.