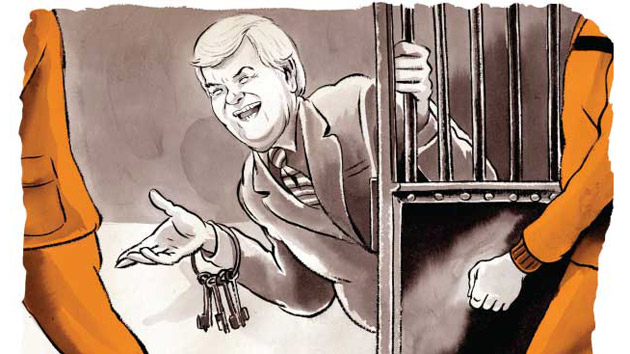

In November 2012, Californians voted in favor of the Three Strikes Reform Act (Proposition 36); no longer would their state be the only one to punish minor crimes with a life sentence. As a result, almost 3,000 inmates—some of whom had been sentenced to life for crimes like stealing a pair of socks—were immediately eligible for parole.

The ballot proposition had been written by Stanford Law professor Mike Romano, whose Three Strikes Project now had a new challenge on its hands: representing possible parolees at their hearing, and trying to line up transitional housing and services for them. Because just as California didn’t consider the harm that Three Strikes would have on families and communities, it was now about to release those same prisoners without much, if any, support. Where would they go? What would they do? What was left of the life they’d left behind? And how to avoid the pitfalls that landed them in prison in the first place?

The Return, a film by Kelly Duane de la Vega and Katie Galloway that airs Monday night on PBS’s POV series, follows two men as they try to reintegrate into society: Kenny Anderson, whose children and ex-wife welcome him back into their lives, but who struggles with mental-health issues, and Bilal Chatman, whose story of redemption is possibly the most heartwarming thing I’ve seen all year. (See John Oliver interview him here.)

But Kenny and Bilal were lucky to have or forge support systems. Many parolees have none. They are often released with no warning. Sometimes in the middle of nowhere with no way to get home—if home still exists. Some jurisdictions deny federal food benefits to ex-cons with drug convictions. Relatives who live in public housing may be prohibited from even letting relatives with a drug record visit. And of course, job applicants who admit to a felony can be automatically banned. The list of barriers go on and on. No wonder half of all parolees reoffend.

Given that 95 percent of all inmates will eventually be released, it is in all of our best interest to help them try to succeed when they get out. The Return will take you on a roller coaster of emotion—a not insignificant portion of the San Francisco Film Festival audience I saw it with were openly sobbing—but you’ll be left with an unshakable conviction that the horrors of mass incarceration don’t end upon release.

Interest declared: I know Kelly, Katie, and Mike. And also Jon Mooallem, who wrote a lovely piece about two ex-cons who drive to distant prisons to make sure parolees get a lift home for the New York Times Magazine.