In the early 1970s, the US Army had a serious problem with its brand. It was stuck in an unpopular and bloody war. Morale stank; even President Richard Nixon conceded to West Point cadets that “it is no secret that the discipline, integrity, patriotism, self-sacrifice, which are the very lifeblood of an effective armed force…can no longer be taken for granted in the Army.” Plus, Nixon had promised to stop the draft and the Pentagon had agreed to reintroduce an all-volunteer force in 1973. That meant military brass could no longer rely on a steady stream of warm bodies to fill the ranks—they would have go out and convince new recruits that Army life wasn’t a drag.

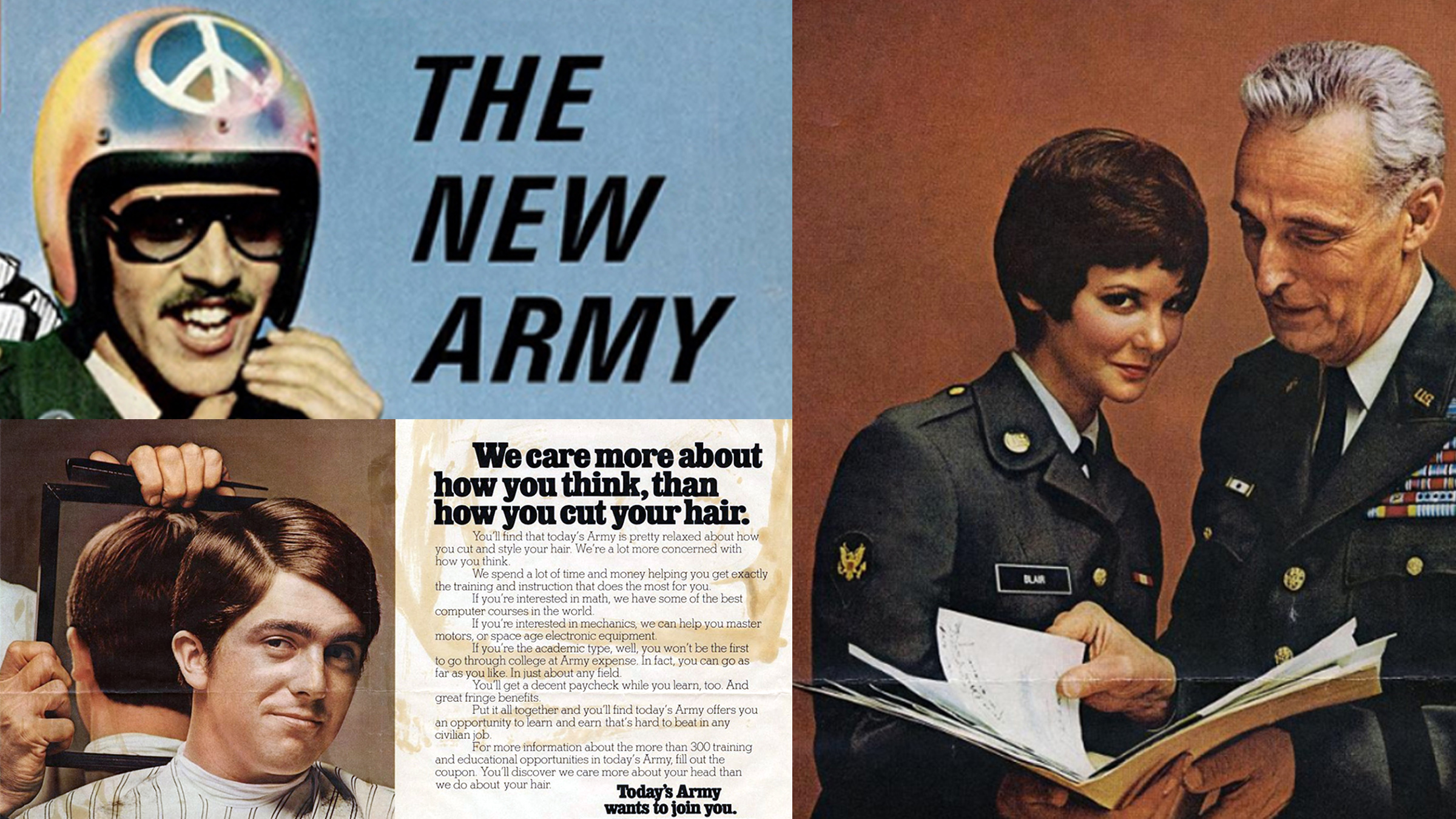

So in 1971, the Army enlisted Madison Avenue to help. Not literally Madison Avenue, but N.W. Ayer, a venerable Philadelphia advertising firm that held the Army recruitment account and had coined copywriting gems such as “A diamond is forever.” Armed with a $18.5 million budget—a sixfold increase from 1970—would-be Don Drapers and Peggy Olsons started brainstorming ways to sell the Army to a target demographic that had come of age amid peace protests and love beads.

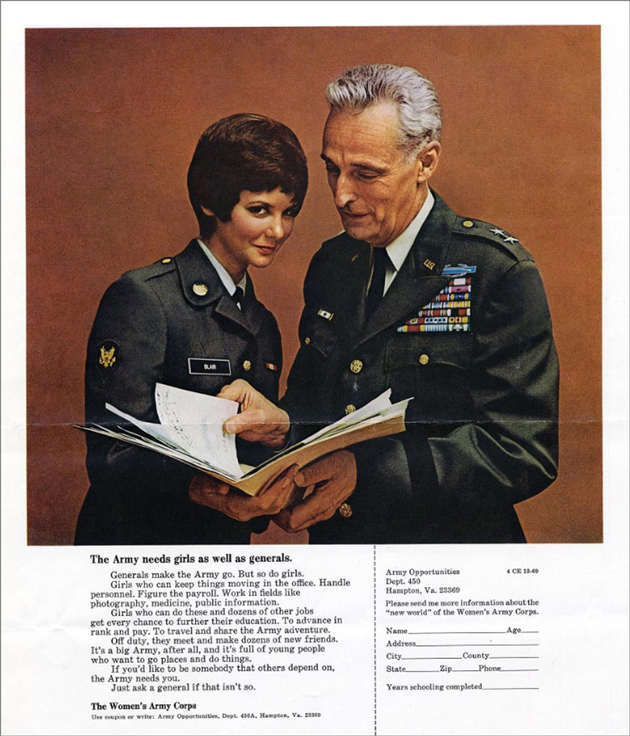

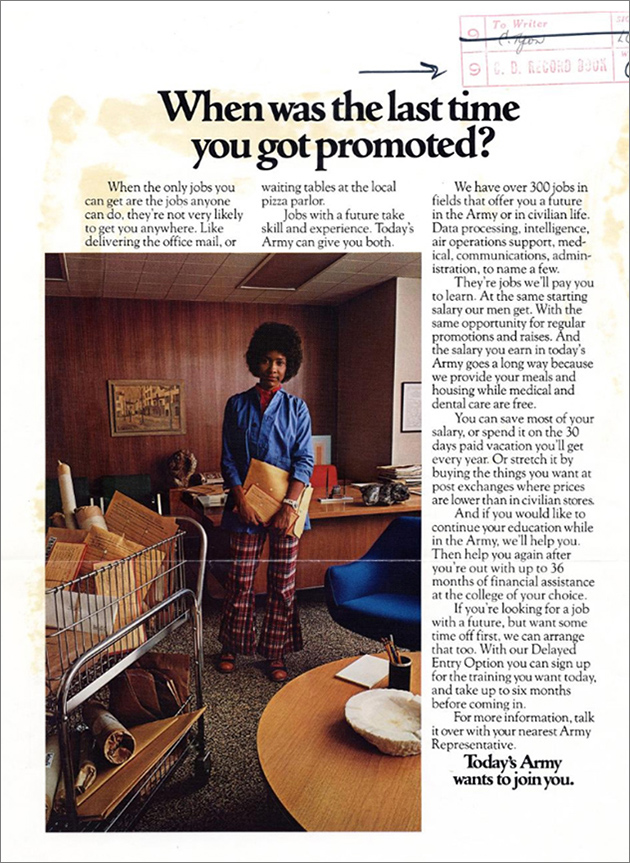

This wasn’t the first time Ayer had tried to convince young Americans that the military got them. In 1969, it created an ad targeting young women titled “The Army Needs Girls as Well as Generals.” Beneath a photo of an aging staff officer and his fresh-faced assistant—his hand creepily touching hers beneath a manila folder—the ad gushed about the need for “girls who can keep things moving in the office.” And if the chance to wage bureaucratic warfare in a potentially hostile work environment wasn’t enticing enough, the copy promised the chance to meet “young people who want to go places and do things.”

The generals who oversaw the 1971 Army rebranding project were unimpressed by Ayer’s initial pitches. One rejected concept, described by historian Beth Bailey, featured an image of a chicken wearing dog tags with the tag line “Bye Bye Birdie.” (Sorry, Sal Romano.)

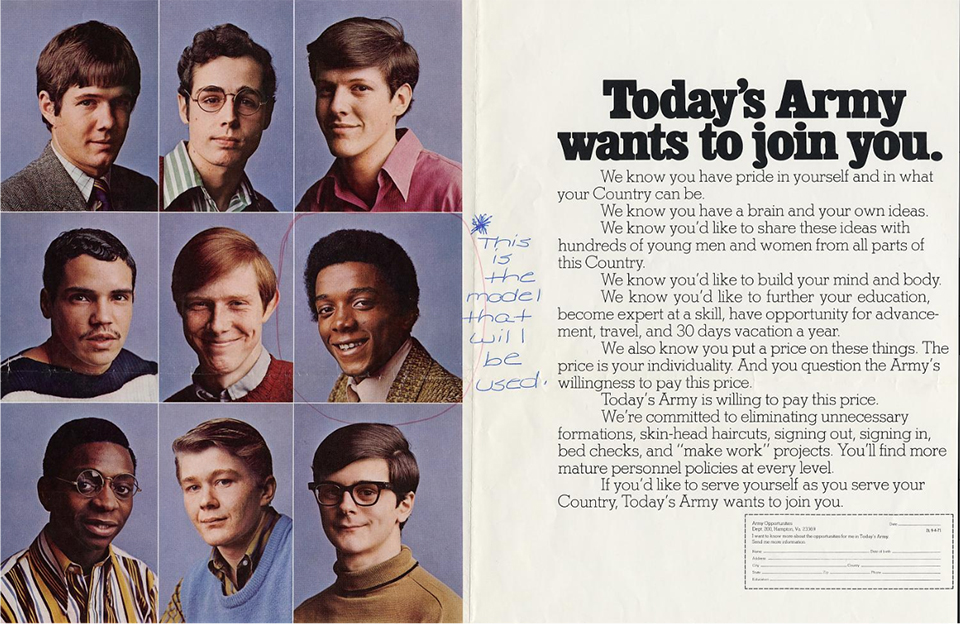

Eventually, the firm sold a reluctant Army Chief of Staff General William C. Westmoreland on the slogan “Today’s Army Wants to Join You”—a twist on the old “I Want You for U.S. Army” posters that one ad exec said was meant to evoke “individual expression and changing lifestyles.” (The other branches of the armed services also deployed new slogans to woo the Me Generation: the Navy: “If you’re going to be something, why not be something special?” The Air Force: “Find yourself in the United States Air Force.”)

The resulting youth-friendly campaign featured a variety of print ads published in mainstream magazines such as Popular Science and Field and Stream. Ads aimed at African Americans ran in Ebony, Jet, and other black magazines. “When was the last time you got promoted?” asked an ad depicting a young African American woman in an office. There was no mention of doing a general’s paperwork; instead, the ad talked up interesting work—”at the same starting salary our men get.”

The campaign also included TV and radio ads as well as records like the one below. Inconveniently, Bailey notes, the TV spots rolled out just as Lt. William Calley was being tried for his role in the 1968 My Lai massacre. A survey found that the ads didn’t shift young men’s interest in enlisting; some unswayed viewers called them “slick garbage.” The TV campaign ended after three months and its funding was not renewed. But Westmoreland later reported that the short-lived campaign was “eminently successful.”

The external rebranding effort was matched by an internal one. In preparation for the end of the draft, the Army rolled out reforms at a few bases as part of Project VOLAR (Volunteer Army). Changes included an end to reveille and bed checks, fewer inspections and more privacy, and other moves toward easing discipline and breaking down military hierarchy. Commanders could even allow the sale of low-alcohol beer in mess halls and barracks.

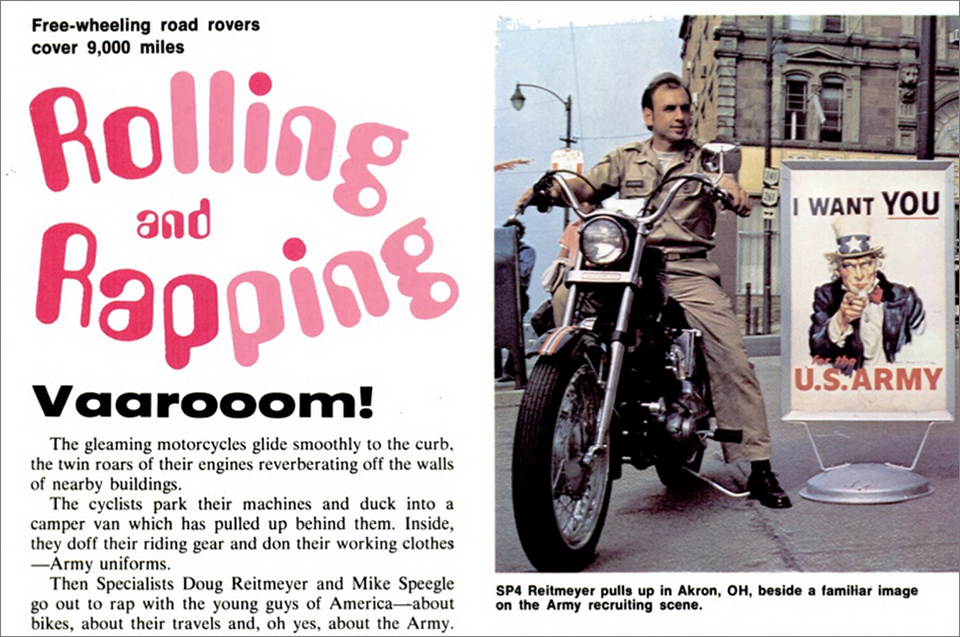

In 1971, a couple of recent enlistees hit the road on their motorcycles on a new kind of recruiting mission. “Rapping with kids on street corners, at dances, at bowling alleys and high schools from New York to Baton Rouge,” according to the Soldiers magazine, the duo talked up the perks of the new, laid-back Army. At one high school, Specialist Mike Speegle boasted about his two-person room: “I had black light posters, peace signs, a little styrofoam beer cooler in the corner.”

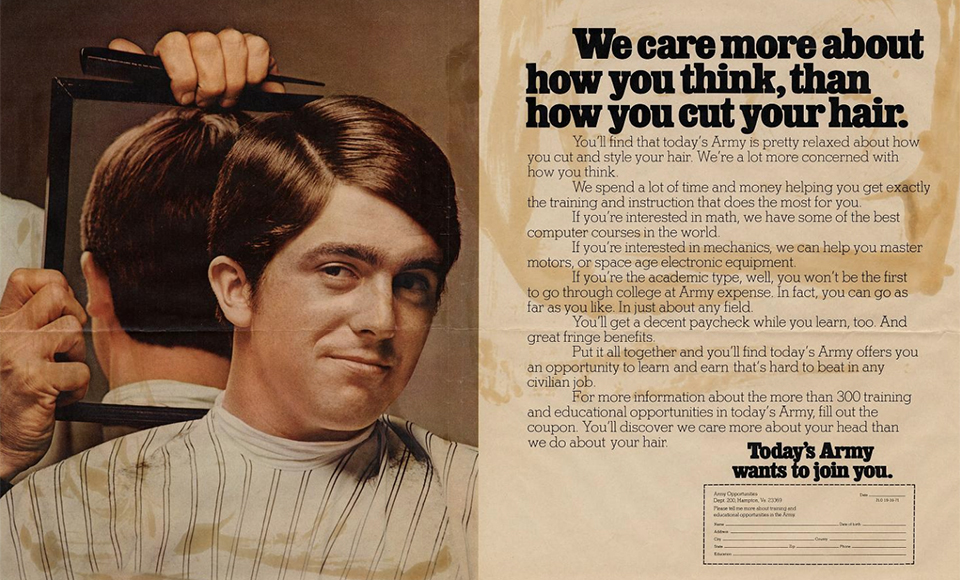

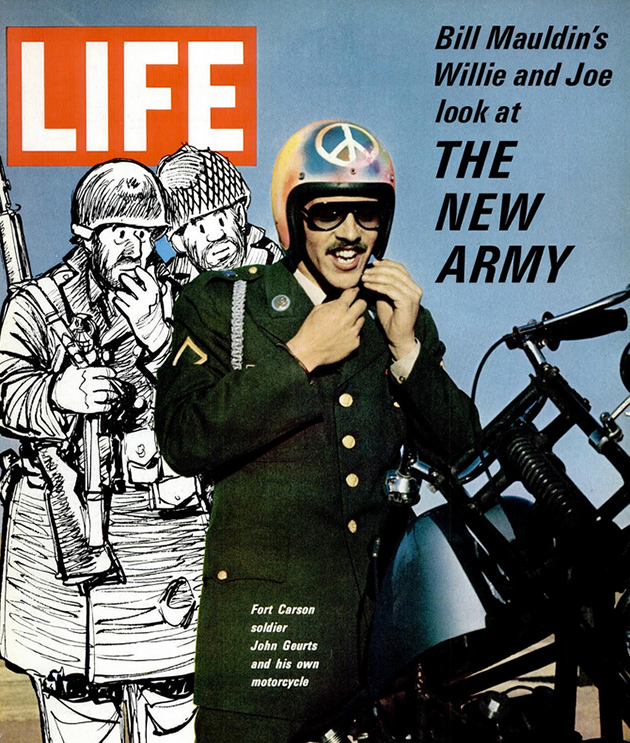

The changes went all the way to the top. Following “an extensive study of Army policy on haircuts,” restrictions on longer hairstyles, sideburns, and mustaches were eased. A LIFE magazine article on “liberated” Fort Carson, Colorado, reported that the new three-inch haircut rule allowed “enough for a spectacular Afro.” One recruitment ad focused on the new hair policies. “You’ll find that today’s Army is pretty relaxed about how you cut and style your hair,” it read. “You’ll discover that we care more about your head than we do about your hair.”

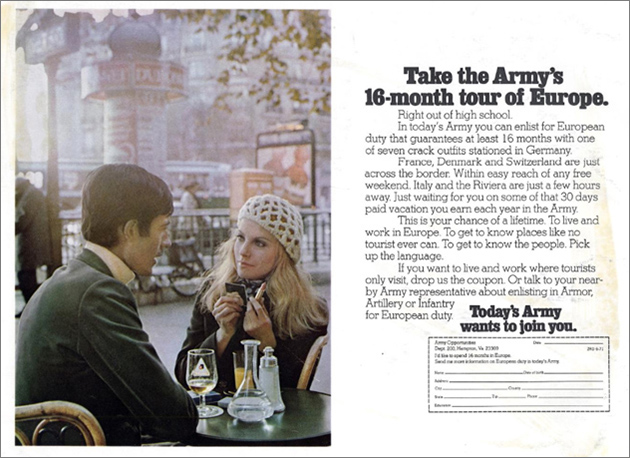

The closest the “Today’s Army” campaign came to acknowledging the Sexual Revolution was an ad that suggested a tour of duty in Germany was a chance to see some action. In it, a GI in civvies and almost-civilian-length sideburns fraternizes with an attentive blonde at what looks like a Parisian café.

By the mid-1970s, many of the VOLAR reforms were scrapped. Officers and lawmakers alike worried that the changes, exemplified by the “Today’s Army…” slogan, were indicators of deteriorating post-Vietnam morale and readiness. “Because of slogans like that, and because of the felling that they have beer in the barracks, no reveilles, and things like that, it was perceived by a great many Americans that the Army would be an undisciplined Army,” Secretary of the Army Bo Callaway told members of the Senate Armed Services Committee in 1974.

In 1973, “Today’s Army Wants to Join You” was replaced with a new slogan, “Join the People Who’ve Joined the Army.” (N.W. Ayer would later lose the Army account after a kickback scandal.) But the campaign’s basic message—that a stint in uniform was a chance for self-realization rather than mindless submission to conformity—would remain a fixture of future recruitment campaigns, from “Be All You Can Be” to “An Army of One.”