Debi Cornwall’s Welcome to Camp America: Inside Guantánamo Bay (Radius Books) is an exhaustively researched, exceptionally photographed documentation of one the most heavily guarded prisons in the world. The way in which photographs, interviews, and government documents intersect and overlap in a multifaceted layout makes the physical book itself becomes important to the narrative. As Cornwall says, the fold-over pages and other layout elements invite the reader to either “take what is given or choose to dig a little deeper.” It’s rare to find a photobook in which the book doesn’t just act as an outlet, but actually amplifies the power of the work within.

It’s no surprise that access at Guantánamo proved to be restrictive, even for Cornwall, who was first granted access in 2014 after a nine month clearance process. What can and can’t be photographed on the base is highly controlled. When shooting film, she had to develop the work on base, under control of military censors. Working within those confines, Cornwall’s work focuses on life and the every day elements at Gitmo—for US military personnel and, as much as possible, for detainees. Most of her photos, though, are hauntingly empty—empty cells, empty restaurants, empty golf courses. Operational security largely prevents the inclusion of people in photos. In the rare instance people appear, their back is to the camera.

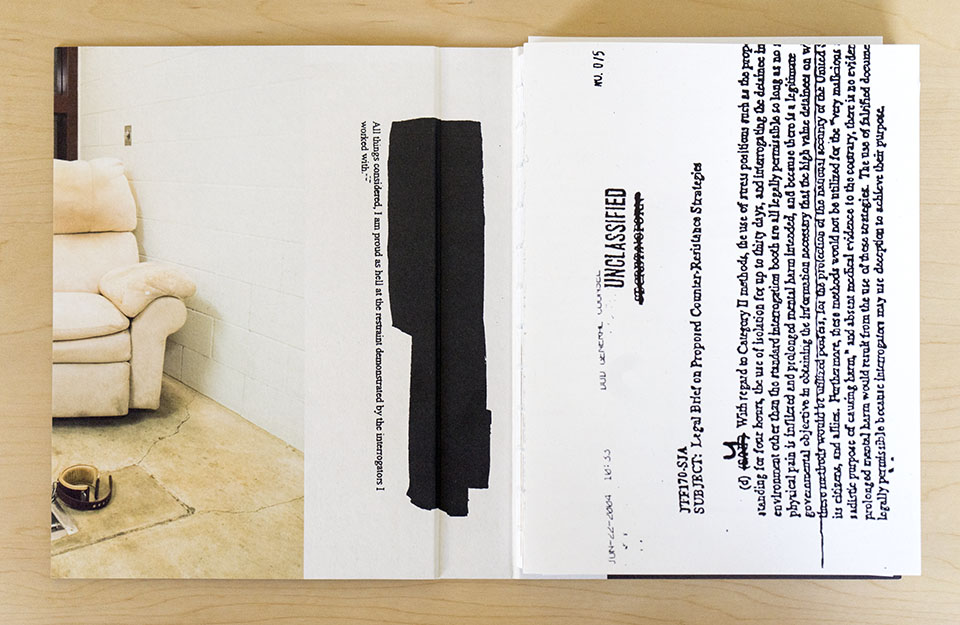

Against this barren backdrop, Cornwall drops in still life photos of items available for purchase at the Gitmo gift shop. You can buy a bobblehead Fidel Castro ($20), a Camp X-Ray coffee mug ($7.99), plush rasta iguana ($4.99), I LOVE Gitmo lip balm (price not available). It’s easy to laugh when you’re on this side of the fence. But not all the still life images portray such a queasy playfulness. Cornwall also photographed items not available at the gift shop: shackles used to restrain detainees ($142.50), detainee-issue shoes ($8.59/pair), shirts ($21.95), and trousers ($26.95). It’s surreal mix of images, made only more disorienting by the inclusion of the government documents—partially redacted, naturally.

Recreation Pen, Camp Echo

Liberty Center Band Room (Analog 2015)

Right: Turkey Vulture ($11.99); Left: Toddler Tee ($6.99)

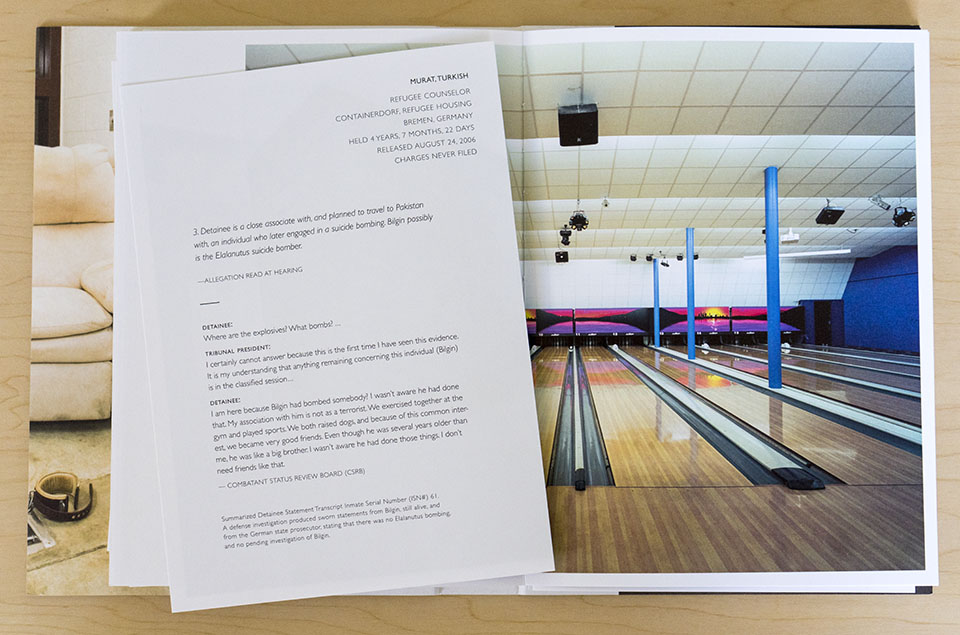

What makes Camp America different from other photo projects on Guantánamo Bay—like Louie Palu’s excellent Guantánamo, Paolo Pellegrin’s multimedia piece of the same name, or Christopher Sims’ project from 2009—is the inclusion of 14 inserts containing portraits of former detainees who have been released. Like the few soldiers who appear in the book, the detainees are photographed with their backs to the camera, faceless. But unlike the US soldiers we see in the book, these men are not completely anonymous. The inserts include basic information: where they’re from, their current occupation, where they’re photographed, how long they were held, when and where they were released, and the charges filed (if any). This humanizing aspect of the book, buffeted by pieces of interviews with detainees dropped in throughout the book, make it so much more than a quirky look at a secretive, tropical military base. Cornwall plunges you just a little into the utter madness of Guantánamo.

Held: 11 years, 11 months, 18 days

Cleared: October 9, 2008 & May 8, 2009

Released: December 4, 2013

Charges: never filed in U.S.

Acquitted and exonerated at trial in Algeria.

Looking homeward, outside Algiers

Murat, Turkish German (Germany)

Murat, Turkish German (Germany)Refugee counselor

Held: 4 years, 7 months, 22 days

Released: August 24, 2006

Charges: never filed

Containerdorf, Refugee Housing, Bremen

“Guantánamo Bay’s detention centers have now been open for more than fifteen years,” writes Cornwall in an essay in the book, which is heavily and powerfully influenced by her past as a civil rights lawyer focused on wrongful convictions. “Of the 780 men who have been held there, only eight have been convicted in the military commissions, and five of those convictions were overturned on appeal. Nine captives have died. Hundreds have been cleared and released, returning home or, if U.S. authorities deemed it necessary, transferred to third countries pursuant to secret agreements between governments. As of this writing, 61 men remain in custody.”

The book also includes essays from the president of the International Center of Photography, Fred Ritchin, and from a former Guantánamo detainee named Moazzam Begg. All text in the book is printed in both English and Arabic—an important nod to the book’s audience beyond the usual English-speaking crowd. All these elements push this book past a mere photobook. It’s an important documentation of an awful period in America’s history, one that, it should be noted, is ongoing.

“Placing ‘War on Terror’ captives,” Cornwall writes, “on an offshore military base has on one level been a great success: out of sight, out of mind. Over the last fifteen years, most Americans have stopped looking.”

Welcome to Camp America will be on exhibition at New York’s Steven Kasher Gallery, 26 October through 22 December, 2017 with a panel discussion, 28 October 2:30-4pm.